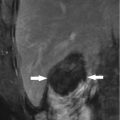

Fig. 9.1

Microwave ablation (MWA) in a 75-year-old woman with liver tumor (3.3 × 3.1 cm) adjacent to the hepatic hilum. (a) Grayscale ultrasonography before MWA showed an isoechoic tumor adjacent to the hepatic hilum (arrow). (b) Color Doppler showed tumor (arrow) adjacent to portal vein (narrow arrow). (c) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) before MWA showed mild enhancement of the tumor in arterial phase (arrows). (d) Contrast-enhanced CT before MWA showed low enhancement in portal venous phase (arrows). (e) Contrast-enhanced axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 4 months after treatment showed no enhancement of the tumor in arterial phase (arrow). (f) Coronal MRI 4 months after treatment showed no enhancement of the tumor in portal venous phase (arrow)

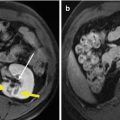

Fig. 9.2

Microwave ablation (MWA) in an 85-year-old man with liver tumor (3.2 × 3.0 cm) adjacent to the hepatic hilum. (a) Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before MWA showed the tumor with high enhancement in arterial phase (arrow). (b) Contrast-enhanced MRI before MWA showed the tumor with low enhancement in portal venous phase (arrow). (c) Coronal MRI showed the lesion adjacent to the hepatic hilum (small arrow); besides, there were multiple cysts in the liver (thick arrow). (d) Contrast-enhanced axial MRI 1 month after treatment showed no enhancement of the lesion in arterial phase (small arrow). (e) Axial MRI 4 months after treatment showed no enhancement of the tumor in arterial phase (arrow). (f) Coronal MRI 4 months after treatment showed no enhancement of the tumor in portal venous phase (arrows)

9.7 Complications

Heat injury to adjacent bile ducts remains a problem because bile flow is slow and has little cooling effect in contrast to blood flow, and MWA may ablate surrounding tissue of antenna rapidly because of higher thermal efficiency [15, 19]. Excessive heating to overcome the “heat sink effect” of hilar large vessels can cause significant damage to the major bile ducts. Bile duct stricture may develop weeks to months after thermal ablation due to heat damage to the bile duct [14, 20]. Strictures of the peripheral bile ducts may not cause any symptoms, but that of the central bile ducts can cause cholestasis, biliary infection, liver abscess, or injury of liver function. Complications related to bile duct injury were reported to occur in between 0 and 25.6 % with an average of 11.7 % [21]. In Liang’s study [17], 1,136 patients with 1928 malignant liver tumors underwent ultrasonographically guided percutaneous MWA; the incidence of bile duct injury was 0.2 % (2/1,136). One patient with an HCC 10 mm away from the hepatic hilum underwent three sessions of MWA. CT depicted dilatation of the right hepatic duct owing to bile duct stenosis near the hepatic hilum 32 days after MWA; the dilatation was relieved by placing a stent. The other patient with a metastasis 7 mm away from the hepatic hilum underwent two sessions of MWA. A biloma was detected 38 days after MWA, and it was cured after 3 months of drainage. In Ren’s study [16], MWA was performed together with percutaneous ethanol injection on 18 malignant liver tumors adjacent to the hepatic hilum, and thrombosis was found in the right portal vein and the umbilical part of the left portal vein by CEUS in one patient 1 month after treatment, which disappeared 3 months later without any management, but no injury to the bile duct occurred.

9.8 Technique Key Points of MWA

In order to gain complete ablation of the tumor and avoid relative complications, there are some key points: (1) carefully consider the route of antenna insertion and the anatomical relationship between the tumor and the portal vein and main bile duct on ultrasound scrutiny; (2) to gain complete ablation of the tumor periphery adjacent to the hilum, percutaneous ethanol injection is performed simultaneously with microwave emission to augment the effect of MWA; (3) to avoid bile duct injury during ablation, long-duration, low-power (45–50 W) ablation and intermittent microwave emission should be performed, and real-time temperature monitoring during MWA may help to prevent thermal-mediated bile duct injury; and (4) MWA can be used in combination with other techniques to augment the ablation effect, such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), intraductal chilled saline perfusion (ICSP), and estimation of spatial location of the tumor by 3-D visual software.

9.9 Other Local Techniques

Other thermal ablation techniques include radiofrequency ablation, high-intensity focused ultrasound, laser ablation, and percutaneous ethanol injection, among which radiofrequency ablation gets the most popularity in the treatment of malignant liver tumors. However, no special study is reported on the ablation effect of tumors adjacent to the hepatic hilum, so the clinical efficacy could not be determined accurately. Here, clinical efficacy and complications of ablation of malignant liver tumors in high-risk locations by these ablation techniques are summarized.

9.9.1 Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA)

Tang et al. [22] evaluated the feasibility and safety of ultrasound-guided RFA of hepatic tumors in high-risk areas (163 patients, including 20 tumors close to the hilum, 11 in the caudate, 79 adjacent to the capsule, 24 near the gallbladder, and 29 cases against the diaphragm) in comparison with those in low-risk areas; there was no mortality or major complications in either group, and they concluded that RFA using cool-tip electrodes for liver tumors in high-risk areas is comparable to those in low-risk areas in the aspects of complete ablation, complications, and mortality.

In a study of three patients with tumors within 3–5 mm to the central bile ducts, Elias et al. [23] performed an open intraoperative choledochotomy, inserted a catheter, and continuously perfused the intrahepatic bile ducts with chilled Ringer solution during radiofrequency ablation. No signs or symptoms of biliary stricture showed up in the 3-month follow-up period after radiofrequency ablation, and no imaging performance of biliary stricture was found on the follow-up CT or MRI at 3 months. In another study of Elias [8], radiofrequency ablation was performed for 13 patients with liver tumors less than 6 mm away from the central bile duct. Thermal-mediated injury of bile ducts was avoided by cooling the main bile ducts (right, left, or both) with a 4 °C saline solution quickly infused by a catheter introduced inside the bile duct through an intraoperative choledochotomy.

Takaya et al. placed a nasobiliary tube endoscopically before radiofrequency ablation and performed intraductal chilled saline perfusion (ICSP) during RFA. Of the 40 enrolled patients, only one had biliary injury, whereas the remaining 39 patients were able to avoid it. Moreover, the liver function 6 months after RFA was also better preserved according to Child–Pugh grading, thus resulting in a better clinical outcome [24].

The combination of radiofrequency ablation and percutaneous ethanol injection in the management of HCC in high-risk locations has a slightly higher primary effectiveness rate than radiofrequency ablation alone. Wong et al. [25] compared the outcome of the management of high-risk tumors with PEI and radiofrequency ablation (n = 50) or radiofrequency ablation alone (n = 114) with the outcome of radiofrequency ablation of non-high-risk tumors (n = 44). The results showed that the primary effectiveness rate of high-risk radiofrequency ablation and PEI (92 %) was similar to that of non-high-risk radiofrequency ablation (96 %). The primary effectiveness rate of high-risk radiofrequency ablation and PEI was slightly higher (p = 0.1) than that of high-risk radiofrequency ablation (85 %). The local tumor progression rates (21 % vs. 33 % vs. 24 % at 18 months) were not statistically different (p = 0.91). Patients with and those without high-risk tumors had equal survival rates (p = 0.42) after 12 (87 % vs. 100 %) and 24 (77 % vs. 80 %) months of follow-up.

9.9.2 High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU)

Franco et al. [26] performed ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound on tumors in difficult locations (including four tumors no more than 1 cm to the main bile duct); in a median follow-up period of 12 months, no bile duct injury were detected. They drew the conclusion that ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation could be considered a safe and feasible approach to the management of solid tumors in difficult locations.

9.9.3 Laser Ablation (LA)

Francica et al. [27] treated 116 HCC nodules in high-risk sites (high-risk group, including 16 nodules adjacent to the hepatic hilum) and 66 nodules located elsewhere (standard-risk group) in 164 cirrhotic patients by laser ablation; the results during an overall median follow-up of 81 months (range, 6–144 months) showed that the initial complete ablation rate per nodule (92.2 % vs. 95.5 %, respectively; p = 0.2711), rates of major complications (1.9 % vs. 0 %), and minor complications (5.6 % vs. 1.0 %) were not statistically different between the two groups. There was no significant difference in either the cumulative incidence of local tumor progression (p = 0.499) or local tumor progression-free survival (p = 0.499, log rank test) between the two groups. They concluded that tumor location did not have a significant negative impact on the technique’s primary effectiveness or safety or on its ability to achieve local control of disease during laser ablation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree