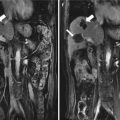

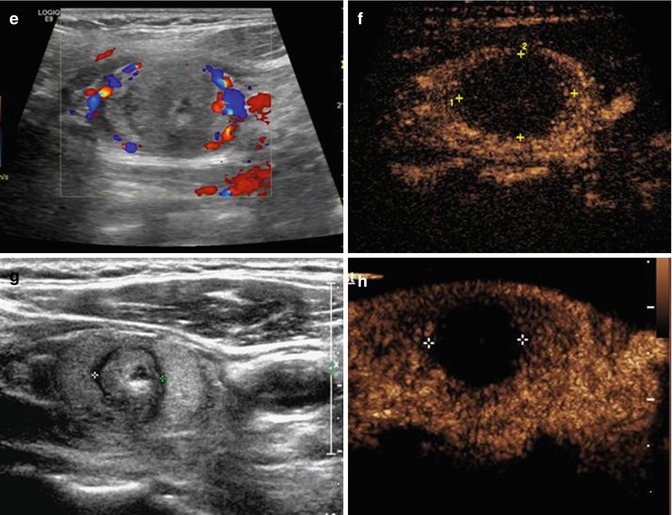

Fig. 19.1

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation (MWA) in a 47-year-old female patient with thyroid oxyphilic adenoma with a volume of 3.3 ml. The nodule is on the right thyroid lobe. (a) Before MWA, nodule internal vascularity is grade 4 (color signals in >50 % of the nodule). (b) The nodule shows heterogeneous enhancement on contrast-enhanced ultrasound before MWA. (c) Microwave antenna (arrow) is percutaneously placed into the nodule, and multiple echogenic microbubbles started to appear around the antenna tip. (d) Multiple echogenic microbubbles are seen on color ultrasound. (e) Nodule internal vascularity is grade 1 (a few spotty color signals in nodule) after MWA. (f) The ablated nodule shows no enhancement after MWA. (g) Two months after ablation, the ablated nodule volume decreases from 3.3 to 0.6 ml. (h) Two months after MWA, the ablated nodule volume decreases

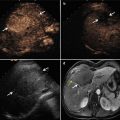

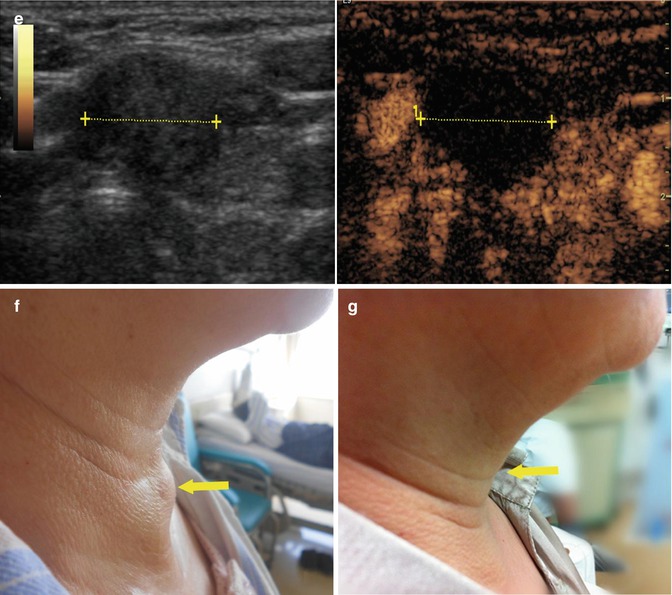

Fig. 19.2

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous MWA in a 63-year-old female patient with nodular goiter. The nodule is on the left thyroid lobe. (a) Preablation conventional ultrasound scan shows a mixed thyroid nodule (arrow) with the size of 3.1 × 2.0 × 2.3 cm (volume, 7.4 ml). (b) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound before MWA shows enhancement on solid portion of the nodule and no enhancement on cystic portion. (c) Percutaneous puncture needle (18 G, Hakko Co, Chikuma-shi, Japan) is inserted to the cystic portion and contained fluid is aspirated. When the cystic portion has completely collapsed, MWA is performed on the solid portion. (d) The ablated nodule shows no enhancement 1 day after MWA. (e) The ablated nodule shows no enhancement with the size of 2.1 × 1.2 × 1.8 cm (volume, 2.4 ml) 6 months after MWA. (f) Before MWA, a walnut-sized nodule can be seen outside the skin of the neck (arrow). (g) Six months after MWA, the thyroid nodule completely disappears and no scars are left on the neck (arrow)

19.8 Complication

Side effects and minor complications of MWA for thyroid nodules include a mild sensation of heat in the neck or slight pain, vasovagal reaction, choking and coughing, slight fever not more than 37.5 °C, mild bleeding or hematoma, vomiting, and skin burn [1, 17]. Yue et al. [9] reported 12 patients (5.4 %) complained of choking and coughing at the end of MWA which disappeared without any treatment (eight patients within 24 h, four patients in a week); besides, a mild sensation of heat in the neck was experienced by most patients, but no one needed the procedure to stop.

The possible major complications of MWA for thyroid nodules include voice change, nodule rupture, abscess formation, hypothyroidism, and brachial plexus injury [17]. In the article of Feng et al., one patient experienced temporary nerve palsy and recovered within 2 months after MWA treatment [1]. Yue et al. [9] reported 3.6 % patients (8/222) complained of voice changes and all patients recovered within 3 months spontaneously. Various technical tips for avoiding complications during ablation of thyroid nodules can be adopted. For example, thermal injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve may be prevented by using the moving shot technique and by undertreating the conceptual units adjacent to the nerve. Hematoma can usually be controlled by mild compression of the neck for several minutes. Intranodular hemorrhage can usually be well controlled by means of direct ablation of the hemorrhagic focus. In addition, modified small-bore antenna may decrease the risk of hemorrhage.

19.9 Other Local Techniques

Other local therapies have been employed to treat thyroid nodules (Table 19.1).

Table 19.1

Clinical results of patients with benign thyroid nodules treated by ablation

Author | No. of Pts (nodule) | Treatment type | Solid component (%) | Session | Follow-up (months) | Initial volume (ml) | 1 month VR (%) | 6 months VR (%) | Last VR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Feng et al. [1] | 11 | MWA | 20–100 | 1–2 (1.1) | 1–9 | 5.3 | N/A | N/A | 46 |

Yue et al. [9] | 222 (477) | MWA | 0–100 | N/A | 6 | 2.1 | −0.1 | 65 | 38 |

Jeong et al. [18] | 236 (302) | RFA | 0–100 | 1–6 (1.4) | 1–41 | 6.1 | 58 | 85 | 84 |

Spiezia et al. [19] | 94 | RFA | >30 | 1–3 (1.4) | 12–24 | 24.5 | 54 | N/A | 79 |

Lim et al. [20] | 111 (126) | RFA | 0–100 | 1–7 (2.2) | 49 | 9.8 | N/A | 70 | 94 |

Valcavi et al. [21] | 122 | Laser | >80 | 1–4 (2.4) | 36 | 23.1 | 6.2 | 47.5 | 47.8 |

Dossing et al. [22] | 78 | Laser | 100 | N/A | 12–114 (67) | 8.2 | N/A | N/A | 51 |

Tarantino et al. [23] | 125 (127) | EA | 0–100 | 1–11 (3.9) | 9–144 | 10.3 | N/A | N/A | 66 |

Raggiunti et al. [24] | 110 | EA | 0 | N/A | 12–84 | 15 | N/A | N/A | 93 |

Kim et al. [25] | 27 (30) | EA | >50 | 1–2 (1.2) | 6–30 | 8.4 | N/A | N/A | 64.3 |

19.9.1 Ethanol Ablation

Since Livraghi et al. [26] used US-guided EA for the treatment of hyperfunctioning thyroid nodules, many published studies have reported appreciable efficacy of EA in treatment of benign thyroid nodules [25, 27]. Advantages of EA include low cost, low risk, practicability in the outpatient clinic, and ease of performance [25], but EA has side effects related to the leakage of ethanol outside the capsule of nodule and the need for multiple ethanol injections. The side effects include extraglandular fibrosis, vocal cord paresis, hematoma, and mild to severe pain [23, 28]. Compared with MWA, EA is very effective when used to treat cystic thyroid nodules, but EA is less effective in solid nodules.

Regarding cystic thyroid nodules, Verges et al. performed EA on nine patients with recurrent large thyroid cysts following aspiration; mean volume was significantly reduced from 31.3 to 9.9 ml, the mean percentage volume reduction was 72.7 %, and a size reduction of the thyroid lesion more than 50 % was achieved in 89 % of patients [29]. In the study of 110 patients with thyroid cyst or pseudocysts treated with EA reported by Raggiunti et al., volume was reduced by 82.6 % after 12 months and 93.03 % after 84 months [24]. There are some factors relating to the efficacy of EA on cystic or predominantly cystic thyroid nodules. Kim et al. [30] found that vascularity and initial volume were independent factors of efficacy in predominantly cystic nodules [30]. From a study of 64 benign cystic nodules treated with EA, In et al. found that the degree of aspiration and color of aspirates correlated significantly with the success of EA [27].

Because of the efficacy of EA on benign cystic thyroid nodules, predominantly cystic nodules are often treated with both EA and RFA to enhance the efficacy [31]. Kim et al. treated 8 of 18 post-RFA nodules with EA because of incomplete ablation, two of which showed marked hypoechogenicity and no vascularity of the remaining solid components, while three nodules showed considerably decreased echogenicity and vascularity of remaining solid components and three showed no significant decrease or mild decrease in the echogenicity and vascularity [32].

Besides, studies about the efficacy of EA for solid or predominantly solid thyroid nodules have also been published, but the results have been variable and less effective than EA for cystic nodules [25, 27, 31]. Kim et al. performed EA on 30 predominantly solid thyroid nodules in 27 patients and found that the effective rate of EA was 60 % [25]. Thus, EA is rarely selected for the treatment of solid thyroid nodules compared with RFA and MWA, owning to controversy over its efficacy and clinical indications [25].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree