Miscellaneous Abdomen Diseases

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Definition

Focal dilatation of the infrarenal abdominal aorta of at least 150% of the normal diameter (range, 1.4–3 cm; average, 2 cm) is the usual definition of an aneurysm.19 Therefore, aortic dilatation larger than 3 cm indicates a possible aneurysm. Some sources state that 4 cm is clearly diagnostic.19,11 Consultation with an experienced surgeon is indicated when the dilatation reaches a diameter of 5 cm (some say 5.5 cm).

Incidence

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) affects approximately 2% to 8% of the population older than 60 years of age.19 The incidence increases rapidly in men after age 55 years and in women after age 70 years. Surgical emergency from AAA rupture is the major complication. Overall incidence and deaths resulting from AAA are more common in men.7,15 In one screening study of nearly 30,000 65-year-old men, the prevalence of AAA (confirmed by at least two ultrasound studies) was 5%, and 80% of AAAs detected were smaller than 4.0 cm.12

Rupture (Rates and Mortality)

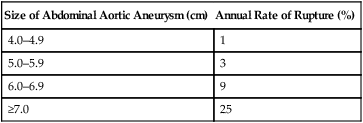

Each year in the United States, more than 15,000 deaths, many of which are preventable, are attributed to AAA.5 The natural history of most aneurysms is one of gradual enlargement; growth rates have been estimated to average 0.2 cm/year for aneurysms smaller than 4 cm and 0.5 cm/year for those larger than 6 cm.19 Although impossible to predict for a given individual, the risk of AAA rupture increases with larger initial aneurysm diameter, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expansion rates of AAAs for men 65 years of age are listed in Table 31-1.12 Rupture of AAA is considered essentially inevitable if the patient lives long enough.15 When rupture occurs, massive intraabdominal bleeding usually occurs and is fatal, with a mortality rate of 80% to 90% unless prompt surgery can be performed.1,4,5,9 A relatively low risk of rupture is seen for asymptomatic, slow-growing AAA smaller than 6 cm. Table 31-2 lists the estimated annual rates of rupture related to AAA.10,19

Risk Factors

The underlying cause of AAA is multifactorial, including such factors as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and inflammation that may lead to dilatation and subsequent plaque deposition.8 Other uncommon possible causes include infection, inflammatory disease, increased protease activity within the arterial wall, genetically regulated defects in collagen and fibrillin, and mechanical factors.8 An individual’s risk is increased 12-fold if a first-degree relative has an AAA.7 In addition to family history of aneurysms, increasing age and male gender are established risk factors. Understanding the established as well as possible risk factors assists the clinician in determining an index of suspicion for the presence of AAA (Table 31-3). AAA is best repaired as an elective, not emergency, procedure.

TABLE 31-3

RISK FACTORS FOR DEVELOPING ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSM

| Established Risk Factors | Comments |

| Increasing age | Most studies focus on ages 65–80 years |

| Male gender | More frequent and at an earlier age than in women. The male-to-female ratio for death from abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is 11 : 1 between ages 60 and 64 years and narrows to 3 : 1 between 85 and 90 years. |

| Family history of aneurysm | Increases individual’s risk twice, especially first-degree male relative |

| Possible Risk Factors | Comments |

| Tobacco use | Long-term smoking increases individual’s risk five times over the baseline |

| Systemic atherosclerosis disease | Including peripheral arterial disease, cerebrovascular disease, history of coronary artery bypass, history of myocardial infarct have modest correlation; less association with smaller AAA than with larger AAAs |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Difficult to establish as an independent risk factor |

| Hypertension | Weak correlation |

| Hypercholesterolemia | Weak correlation, specifically related to hypertriglyceridemia |

| White race | AAAs are uncommon in African Americans, Asians, and Hispanics |

From Ebaugh JL, Garcia ND, Matsumura JS: Screening and surveillance for abdominal aortic aneurysms: who needs it and when, Semin Vasc Surg 14(3):193, 2001; Lederle FA, Simel DL: Does this patient have abdominal aortic aneurysm? JAMA 281:17, 1999; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Guide to clinical preventive services, ed 2, Washington, DC, 1996, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

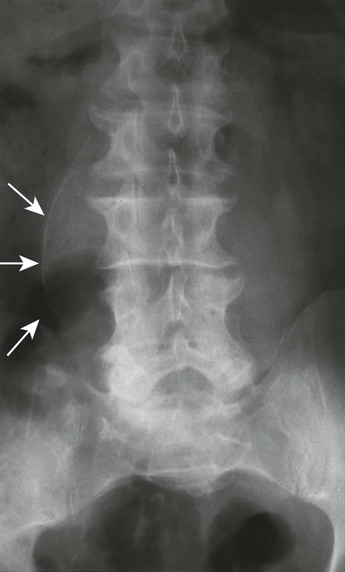

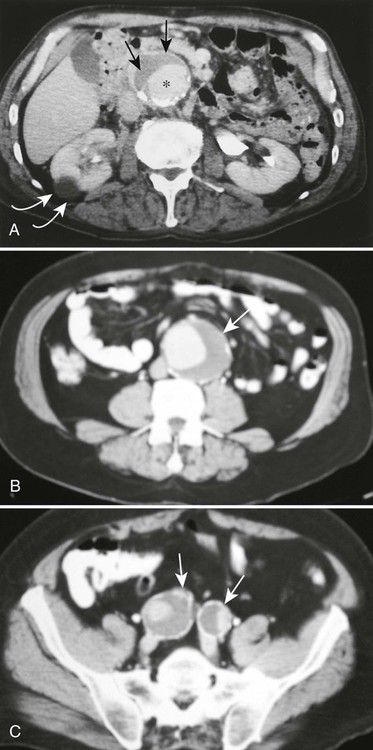

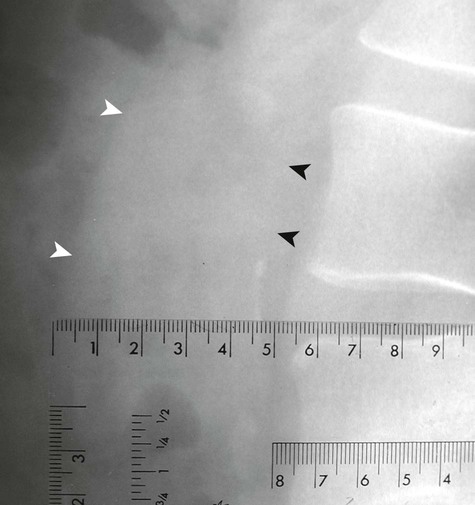

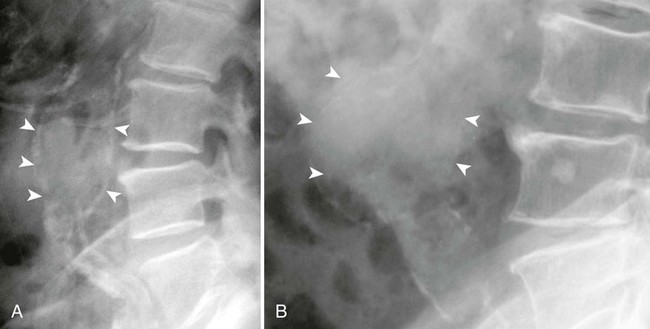

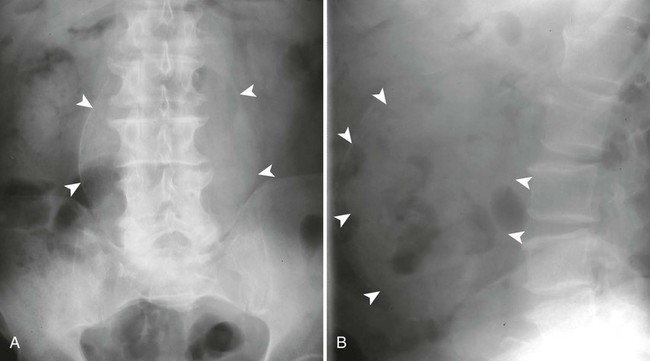

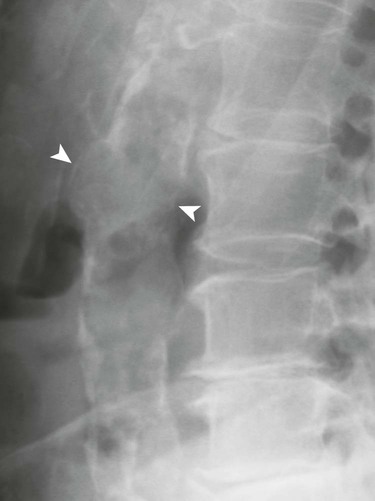

Imaging Findings

Ultrasonography reaches almost 100% accuracy19 for detecting AAA, making it ideal for screening, diagnosis, and follow-up studies in suspected cases.3 Obesity and excessive bowel gas may interfere with ultrasound imaging.15 Approximately 50% of AAAs may be seen as cyst-like calcifications on plain film radiography resulting from the calcium content of atherosclerotic plaques (Figs. 31-1 to 31-11).15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree