Miscellaneous Conditions

BLOUNT DISEASE (CONGENITAL TIBIA VARA)

This anomaly predominantly affects the medial portion of the proximal tibial growth plate, as well as the medial segment of the tibial metaphysis and epiphysis, resulting in a varus deformity at the knee joint. The cause of this condition is unknown, but it is probably a multifactor disorder with genetic, humoral, biomechanical, and environmental factors. Bateson has demonstrated convincingly that Blount disease and physiologic bowleg deformity are part of the same condition, which is influenced by early weight-bearing and racial factors. On the basis of a study of South African black children, among whom there is an increased incidence of this disorder, Bathfield and Beighton have suggested that its cause might be related to the custom of mothers carrying children on their backs. The child’s thighs are abducted and flexed, and the flexed knees gripping the mother’s waist are forced to assume a varus configuration.

Two forms of Blount disease have been identified: infantile tibia vara, which is usually bilateral and affects children younger than 10 years of age, with onset most commonly between ages 1 and 3 years, and adolescent tibia vara, which is usually unilateral and occurs in children between the ages 8 and 15 years. The course of the adolescent form of disease is less severe and its incidence less frequent than that of the infantile form. Regardless of its variants, Blount disease must be differentiated from other causes of genu varum, such as in variety of arthritides.

Imaging Features

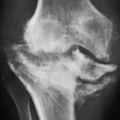

Radiographically, the early stages of Blount disease are marked by hypertrophy of the nonossified cartilaginous portion of the tibial epiphysis and hypertrophy of the medial meniscus, which represent compensatory changes secondary to growth arrest at the medial aspect of the physis. The medial aspect of the tibial metaphysis is characteristically depressed, exhibiting an abrupt angulation and formation of a beaklike prominence, which is associated with cortical thickening of the medial aspect of the tibia. Similar changes are seen in the medial aspect of the tibial epiphysis. Because of the sharp angulation of the metaphysis and adduction of the diaphysis, the tibia assumes a varus configuration (Fig. 14.1). In most instances, the lateral cortex of the tibia remains relatively straight. As the metaphysis and growth plate become depressed, the cartilage decreases in height. In advanced stages of the disease, there is premature fusion of the growth plate on the medial side (Fig. 14.2). The presence of fusion is important information for surgical planning because either resection of the bony bridge or epiphysiodesis (fusion of the physis) would be required in addition to corrective osteotomy. In the past, double-contrast arthrography was a valuable technique in the imaging evaluation of Blount disease, because it permitted visualization of nonossified cartilage of the medial plateau (Fig. 14.3) and associated abnormalities of the medial meniscus (Fig. 14.4). Currently, MRI is the imaging of choice to visualize the condition of the growth plate, the epiphyseal cartilage, and the degree of deformity of the epiphysis and menisci (Fig. 14.5). This information is valuable for preoperative assessment.

Classification

Based on the progression of imaging changes in Blount disease, Langenskiöld divided congenital tibia vara into six stages as a guideline for prognosis and treatment:

Stage I. A varus deformity of the tibia, associated with irregularity of the growth plate and a small beak at the medial metaphysis; usually seen in children from 2 to 3 years of age.

Stage II. A definite depression of the medial portion of the metaphysis, associated with slanting of the medial aspect of the epiphysis; usually seen in children from 2 to 4 years of age.

Stage III. Progression of the varus deformity and a very prominent beak, with occasional fragmentation of the medial portion of the metaphysis; seen in children between 4 and 6 years of age.

Stage IV. Marked narrowing of the growth plate and severe slanting of the medial aspect of the epiphysis, which shows an irregular border; usually seen in children between 5 and 10 years of age.

Stage V. Marked deformity of the medial epiphysis, which is separated into two parts by a clear band, the distal part having a triangular shape; seen in children between 9 and 11 years of age.

Stage VI. An osseous bridge between the epiphysis and metaphysis and possible fusion of the triangular fragment of the separated medial epiphysis to the metaphysis; seen in children between 10 and 13 years of age.

Stages V and VI represent phases of irreparable structural damage.

Recently, Smith introduced a simplified classification of Blount disease in attempt to relate the grade of deformity to the need for treatment. His scheme comprises four grades: grade A, potential tibia vara; grade B, mild tibia vara; grade C, advanced tibia vara; and grade D, physeal closure.

Treatment

Blount disease is usually treated conservatively with braces. If the deformity continues to progress despite such treatment, a high valgus tibial osteotomy may be required to achieve normal alignment of the limb; usually, correction of a rotary deformity requires an osteotomy of the proximal fibula as well. MRI may be required before surgery to determine the status of the tibial articular cartilage, information necessary in planning the degree of angular correction necessary to eliminate the deformity.

SLIPPED CAPITAL FEMORAL EPIPHYSIS (SCFE)

Clinical Features

SCFE is a disorder of adolescence in which the femoral head gradually slips posteriorly, medially, and inferiorly with respect to the femoral neck. Boys are affected more often than girl, and children of both genders with this disorder are often overweight. In boys, the left hip is involved twice as often as the right, whereas in girls, both hips are affected with equal frequency. Bilateral involvement occurs in 20% to 40% of patients.

Although the specific cause of SCFE is obscure, its onset, which is usually insidious and without history of trauma, commonly coincides with the growth spurt at puberty. Studies by Harris have suggested that an imbalance between growth hormone and sex hormones weaken the growth plate, rendering it more vulnerable to the shearing forces of weight bearing and injury. Pain in the hip, or occasionally in the knee, is often the presenting symptom of this condition, and physical examination may reveal shortening of the involved extremity and limitation of abduction, flexion, and internal rotation in the hip joint.

Imaging Features

The radiographic abnormalities that may be seen in SCFE depend on the degree of displacement of the capital epiphysis. The anteroposterior radiograph of the hip, supplemented by a frog-lateral view, is usually sufficient to make a correct diagnosis. Several diagnostic indicators of SCFE have been identified on the anteroposterior radiograph of the hip (Fig. 14.6). The triangle sign of Capener may be of value in recognizing early SCFE. On conventional radiograph of the normal adolescent hip, an intracapsular area at the medial aspect of the femoral neck is seen overlapping the posterior wall of the acetabulum, creating a dense triangular shadow; in most cases of SCFE, this triangle is lost (Fig. 14.7). In a later stage, periarticular osteoporosis becomes apparent, as do widening and blurring of the physis and a decrease in height of the epiphysis. Moreover, as the disease progresses, slippage of the capital epiphysis can be identified by the absence of an intersection of the epiphysis with a line drawn tangentially to the lateral cortex of the femoral neck (Fig. 14.8). The frog-lateral projection of the hip reveals slippage more readily (Fig. 14.8B), and comparison radiographs of the opposite side are helpful. Chronic stages of this disorder exhibit reactive bone formation along the superolateral aspect of the femoral neck, along with remodeling; this creates a protuberance and broadening of the femoral neck, which gives it a “pistol-grip” appearance known as a Herndon hump (Fig. 14.9).

Figure 14.6 ▪ Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Various radiographic findings have been identified as diagnostic clues to SCFE. The insets show the normal appearance. |

MRI is a useful technique in the evaluation of SCFE. This modality, in addition to findings revealed by radiography, may show bone marrow edema of the affected femur and early imaging manifestations of SCFE and pre-SCFE (Figs. 14.10 and 14.11).

Treatment

SCFE is treated surgically by closed or open reduction of the slippage and internal fixation using various types of nails, screws, wires, and pins to prevent further slippage and to induce closure of the physis. Complications of the treatment

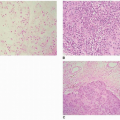

include chondrolysis, which is observed in about 30% to 35% of patients with SCFE. It usually occurs within 1-year after the treatment and is evident by gradually narrowing of the joint space (Fig. 14.12). Osteonecrosis secondary to the precarious blood supply to the femoral head and the vulnerability of the epiphyseal vessels has been reported in ˜25% of patients with SCFE (Fig. 14.13). Secondary osteoarthritis may also occur, and it can be recognized by a typical narrowing of the joint space, subchondral sclerosis, and marginal osteophyte formation (Fig. 14.14, see also Fig. 14.12).

A severe varus deformity of the femoral neck, known as coxa vara, may also be encountered.

include chondrolysis, which is observed in about 30% to 35% of patients with SCFE. It usually occurs within 1-year after the treatment and is evident by gradually narrowing of the joint space (Fig. 14.12). Osteonecrosis secondary to the precarious blood supply to the femoral head and the vulnerability of the epiphyseal vessels has been reported in ˜25% of patients with SCFE (Fig. 14.13). Secondary osteoarthritis may also occur, and it can be recognized by a typical narrowing of the joint space, subchondral sclerosis, and marginal osteophyte formation (Fig. 14.14, see also Fig. 14.12).

A severe varus deformity of the femoral neck, known as coxa vara, may also be encountered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree