2 MRI and Spinal Surgery – Indications Based on the Spectrum of Surgical Therapeutic Options

Contents

General Comments on Preoperative Diagnostics and Planning Strategy

Surgical Management of Spinal Diseases with Reference to MRI

Cervical Intervertebral Disk Prolapse

Operative technique of anterior operations on the cervical spine

Lumbar Intervertebral Disk Prolapse/Degenerative Diseases of the Lumbar Spine

Microsurgical technique for lumbar intervertebral disk procedures

Recess Stenosis and Spinal Canal Stenosis

Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (Post Diskectomy Syndrome)

Intramedullary Tumors and Syringomyelia

Changes at the Craniocervical Junction

Technique of anterior odontoid screw fixation

Technique of posterior C1/C2 screw fixation and cerclage wiring

Technique of posterior craniocervical stabilization

Communication as a Problem of Diagnostics

General Comments on Preoperative Diagnostics and Planning Strategy

In almost all the cases of spinal lesions amenable to surgery, spinal MRI currently allows a very precise diagnosis and guidelines for preoperative planning to be established without direct contact between the patient or examiner and the prospective surgeon. The main indication for spinal MRI is usually to secure a diagnosis.

Any question directed to the examiner regarding the possible level and nature of the lesion must be formulated as precisely as possible and include an exact neurological classification of the clinical findings. This is particularly helpful when no pathological finding has been noted on MRI despite unequivocal clinical symptoms. A disturbance of gait, for instance, can be caused by cervical myelopathy, lumbar spinal canal stenosis, normal pressure hydrocephalus, Parkinson’s disease, disseminated encephalitis, polyneuropathy, an intramedullary tumor or a bone metastasis to the spine, or a spinal AV fistula—only an exact analysis of the patient’s history and the clinical findings will in this case provide the examiner with the necessary data on which to focus the examination technique. It should be borne in mind that an exclusion diagnosis, in particular, can sometimes be technically very demanding.

In addition, information from the surgeon’s point of view regarding operative strategy, which may not necessarily have been offered for a routine examination, might nevertheless become important. In order to make optimal use of the imaging equipment, thoughts about preoperative planning or additional information on how the indication was reached should, if possible, be available for consideration at the initial diagnostic MRI scanning.

The following aspects are of particular interest when a pathological finding amenable to surgery is noted on MRI:

• topographic assignment,

• specific diagnostic classification.

Documentation of level and expansion of the lesion must be precise, i.e., it must be possible for the surgeon to take responsibility for counting off each vertebral segment from the spinal sections depicted on the MR image and to transfer the findings on to plain x-rays and intraoperative fluoroscopy. The neck and upper thoracic spine will therefore require depiction of the vertebral landmarks of the craniocervical junction, and inclusion of the sacrum is necessary for the lower thoracic and lumbar spine. For the mid-thoracic spinal region, it is always obligatory to provide a sagittal reference image that includes the sacrum or the craniocervical junction.

Assigning and labeling the level of individual vertebrae on the image are only helpful when done electronically by the examiner, thus converting it into a permanent document and rendering it legally binding. Otherwise the image must be repeated in order to assure the necessary reliability of the assigned level. Labels on the film may be accurate, but they do not provide any legally binding basis for the site of the operation because it will never be certain with hindsight whether the labeling was done authentically by the examiner or later—and possibly incorrectly—by some other observer. The operative strategy of the much cited minimally invasive surgery requires, in the first instance, an exact localization—a lateralized spinal meningioma, for example, already demonstrated earlier during laminectomy, which had included the adjacent segments, can only be removed microsurgically by a stability-maintaining hemilaminectomy if it is possible during surgery to locate exactly which hemi-arch is to be removed.

It is always compulsory to display spinal disorders in the sagittal and transverse plane, and often preferably in the frontal plane, even though the information value of this frontal slice orientation is limited because kyphosis or lordosis requires an adjustment of the scanning plane for depiction of the spinal canal. It can, however, facilitate orientation in paravertebral lesions of the thoracic and retroperitoneal cavities. Because the plethora of image sections will sometimes require limitation of the final amount of image documentation, it is important that a continuous image series is taken to provide the surgeon with some form of spatial orientation. Omitting seemingly irrelevant images can lead to confusion and faulty assignment of location. Anatomical considerations also play a decisive role when planning the operative approach so that the documented images should allow additional anatomical information to be gleaned as comprehensively as possible and recorded in three dimensions.

The choice of slice thickness and of the interval between individual sections will depend on the dimensions of the lesion in question. For example, thin slices in the region of the tumor are decisive for preoperative planning, particularly with intramedullary tumors. With spinal metastases, on the other hand, it is important that virtually the entire spine is depicted to avoid overlooking tumor formations additional to the metastasis responsible for the symptoms. In case surgical stabilization is required, portrayal of the vertebrae adjacent to the lesion will provide enough assurance that these are not affected by the tumor and can be used for supporting the instrumentation. Since, in this case, priority lies more in including contiguous regions, it is advisable to use thicker slicing. It can be helpful if the relevant images of the various scanning planes are combined on one or a few films. However, this is no substitute for the information value provided by a complete series with regard to anatomical considerations relating to preoperative planning.

With the increasing significance of neuronavigation in spinal surgery, it will presumably be wise in future, when a finding requiring surgery is noted, to electronically store image data sets for later use by the respective neuronavigation systems after consultation with the potential surgeon. Digital documentation of the image data would be ideal, allowing appropriate evaluation at any time. Paper radiographs would then probably suffice for an overview assessment in cases of more complex lesions, where they might otherwise be limited in their informative value.

In view of the number of sections in different planes and sequences, it is helpful if the relevant images are marked with self-stick dots or the like. This can save a considerable amount of time during the overview assessment.

The specific diagnostic classification of the observed findings by the examiner is considerably more relevant than with other imaging techniques. While with CT, for example, an interpretation of the images by others poses no problem as a rule, the appreciation of why a particular MR imaging sequence was selected obviously requires additional diagnostic information that is not always available to those foreign to the matter. It is therefore of utmost importance that the examiner specify the degree of differential-diagnostic certainty of a finding.

MRI is becoming increasingly important for the emergency diagnostics of acute spinal cord paralysis so that attempts should be made whenever possible to widen the availability of this diagnostic procedure, at least on a regional basis, by allowing examinations to be also performed outside regular office hours. A spinal empyema, an epidural hematoma and a central cervical cord lesion are often difficult, or even impossible, to detect with other techniques; the density of information in a case of metastatic disease of the spine can be enlarged rapidly so as to allow well-founded indications to be defined and, perhaps, even considerations regarding an overall oncological concept to be taken into account. Routine diagnostics of spinal trauma using MRI is still certainly a problem because there are only very limited possibilities of monitoring vital signs during the diagnostic work-up. Nevertheless, it should be remembered that, e.g., the diagnostics of traumatic vascular dissection of the cervical spine, a problem area which up to now has been difficult to diagnose despite its primary importance, could be considerably better addressed in the future; a similar widening of the diagnostic spectrum can also be expected for other spinal regions.

The timing of the examination in spinal diagnostics can be decisive for the further course of the disorder. It should, therefore, always be ensured that, for example, when admitting patients with incipient paralysis or disturbance of bladder function as a sign of a transverse spinal lesion, a top-priority emergency appointment for the examination is given. The urgency depends here on the severity of the symptoms so that in the presence of marked neurological deficits an immediate examination should be performed.

Should a space-occupying mass of the spine be identified, it is wise to contact the surgeon immediately in order to make urgent arrangements for surgery. This can be indicated in the presence of neurological deficits as well as for instability of the spine. Depending on the clinical picture, the examiner will often be required to save time by arranging for immediate and specific referral of the patient. Once the necessity of emergency surgery has been established, it is extremely helpful to tell the patient to remain fasting as a precaution until a final decision on this has been made. It is most important for psychological reasons that patients with malignant tumors in particular are only informed that the opinion of the surgeon should be sought and not that surgery will be necessary. The decision to operate can often only be reached after unraveling a complex array of factors that will eventually define the indication. Especially in the case of oncological patients, hopes of a “still possible” operation can be dashed by the fundamental disappointment that surgery is “no longer feasible”—unnecessarily sometimes if other therapeutic alternatives are to be given priority anyway.

Where the diagnosis automatically dictates the indication for surgery, it is often extremely comforting for the patient to receive information about treatment options from the examiner first. It helps the surgeon if, when introduced, the patient is already informed about this, yet not necessarily about a specific therapeutic procedure. The patient can only reach a decision for or against possible therapeutic measures, which often include a considerable range of variations, after close discussion with the person who will actually perform the operation. Considering the multitude of factors influencing the decision to recommend a specific operative strategy, a discussion unaffected by any previous statements should, in the interests of the patient, be all the more specific. The surgeon is certainly just as grateful to the examiner for his advice in favor of surgery as for his measured restraint regarding concrete remarks on type, extent and time frame of a possible operation.

Surgical Management of Spinal Diseases with Reference to MRI

Objectives underlying operative management can include:

• Removal of a pathological lesion (intervertebral disk prolapse, tumor, empyema, angioma, and the like).

• Stabilization of the either primarily unstable spine or the spine having become unstable after resection of the lesion.

Stabilizing surgery sometimes forms an integral part of a primary decompressive operation, e.g., in surgery for cervical disk prolapse. On the whole there is a general tendency with regard to stabilizing operations towards instrumented spondylodesis, with titanium finding increasing use as an implant system because of the imaging problems otherwise associated with MRI. Reconstructive procedures for maintaining joint function (“disk replacement”) are still undergoing clinical trials.

Cervical Intervertebral Disk Prolapse

MRI is optimal for detecting a soft-disk prolapse and anterior narrowing of the spinal canal or intervertebral foramina by marginal osteophyte formation in the form of a “hard” disk prolapse. The aim of surgery is decompression of the nerve root(s) or the spinal cord. Even if the main feature of the clinical picture is a radicular lesion or cervical myelopathy, equal attention should be paid during surgery not only to sufficient radicular but also medullary decompression.

Anterior diskectomy has become an extremely standardized operation, free of complications, particularly for a “soft” or sequestrated disk prolapse. The removal of bony ridging in a dorsal and, above all, lateral direction (Fig. 2.1) in the form of an uncoforaminotomy is technically more difficult, but the consequential use of this procedure has ultimately optimized treatment results.

The use of (high-speed) burrs, however, often produces metal abrasion from the burr or the metal suction probes, which is highly apparent in situ as artifacts on postoperative MRI follow-up studies. For this reason a CT scan may be preferable in some cases for a reliable postoperative confirmation of adequate decompression. Interposition material used for interbody spondylodesis can also give rise to further artifacts. The use of a round Cloward bone dowel has been largely abandoned for reasons of stability in favor of the Smith and Robinson horseshoe-shaped tricortical iliac crest bone graft (Fig. 2.2), with the implants secured by an anterior metal plate (e.g., the methods of Caspar, Orozko) (Fig. 2.3).

Screw fixation systems where the screws are rigidly fixed to the plate (Morscher plate, ACP plate, Atlantis plate) are also enjoying increasing use. However, these plates are thicker and therefore produce artifact effects. This technique has been modified by the interposition of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA, e.g., Palacos or Sulfix) (Fig. 2.4), titanium and carbon fibers and, albeit rarely, is even used without fusion (with the risk of later kyphosis formation of the cervical spine). Interposition materials can also give rise to artifacts on postoperative follow-up scans (Figs. 2.5 and 2.6).

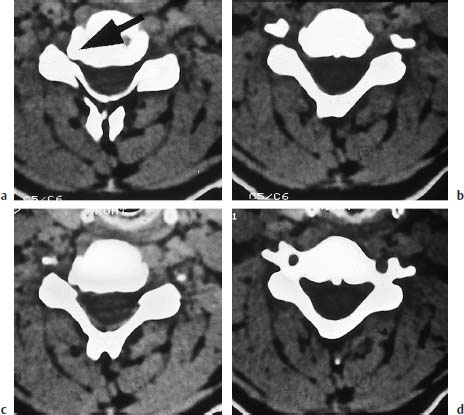

Fig. 2.1a—d Small osteophyte of the cervical spine (arrow) located exactly in the intervertebral foramen and giving rise to radicular symptoms. Removal was made via a so-called anterior uncoforaminotomy.

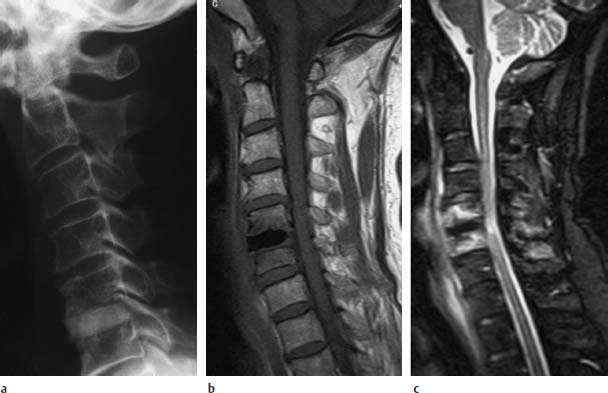

Fig. 2.2a, b Solid bony fusion of the C4/C5 segment:

a Postoperative film after nucleotomy and insertion of an autologous Smith-Robinson bone dowel.

b Preoperative state.

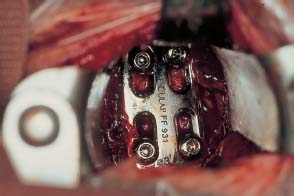

Fig. 2.3 Operative site during cervical fusion. The Caspar plate is seen deep down, stably fixed to the cervical spine by screws.

Fig. 2.4 Fully consolidated cervical fusion of C5/6. Here polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) was used as a spacer, often referred to clinically as a “dowel.” Final fusion is not complete until years after surgery when the PMMA beads are covered on all sides by bone.

For long-segment stenosis of the cervical spinal canal associated with myelopathy, vertebral replacement is increasingly preferred as a technically simpler operation that facilitates extensive decompression of the spinal canal. An iliac crest bone graft, Harms titanium cage (Fig. 2.23) and, less frequently, carbon fibers can be used as interposition materials. The procedure is being increasingly employed for the management of OPLL syndrome (ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament), which occurs frequently, and primarily in Japan, but less often in Germany where it will sometimes be seen as a diagnostic pitfall.

It is essential to establish a diagnosis because of the marked adhesions present between this calcified longitudinal ligament and the dura. Dural tears can appear during resection of the space-occupying mass, so the occurrence of CSF accumulations should be looked for after surgery.

Adequate documentation is important after diagnosing any cervical spine deformity (kyphosis?) or its correction after surgery. For technical reasons the width of the spinal canal can be underestimated on T2-weighted images so that T1-weighted sections should be used for an anatomically correct assessment. Because MR imaging is generally insufficient in depicting bone, the extent of the stenosis can be better assessed on a supplementary CT scan. Dorsal narrowing of the myelon by infolded ligamenta flava is only detectable by MRI on sagittal sections. This narrowing can be surgically corrected by holding the motion segment apart with some form of interposition material, which will require monitoring on follow-up scans after surgery. At times, only MRI will allow the diagnosis of marked diskoligamentous stenoses of the cervical spinal canal on inclination, so that with clinically unequivocal symptoms, but initially inadequate findings, only a view of the cervical spine in maximum anteflexion will provide the exclusion diagnosis of stenosis of the cervical spinal canal.

Fig. 2.5a—c Implantation of a Sulfix dowel:

a Finding after implantation of a Sulfix dowel as a replacement for the removed disk C5/6.

b Note the typical signaling on the T1-weighted image.

c The changes on the T2-weighted image are typical for long-term reactions in the adjacent vertebrae, which can demonstrate marrow edema and fatty marrow formation and cause local symptoms.

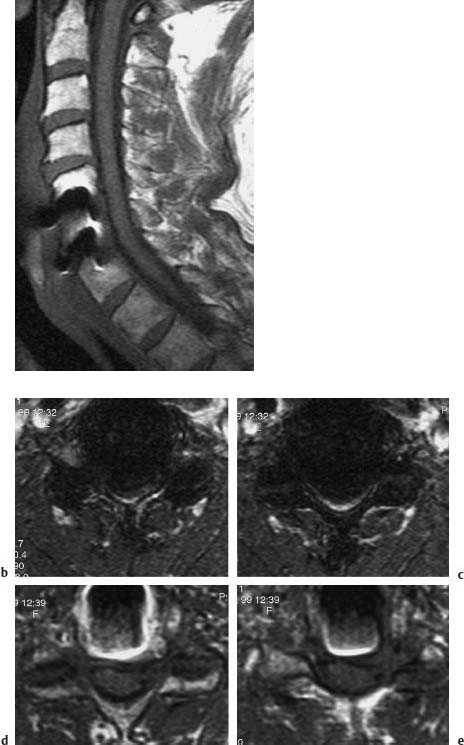

Fig. 2.6a—e Formation of artifacts after implantation of titanium spacers in the intervertebral cavity during surgery for stenosis of the cervical spinal canal secondary to osteochondrotic ridging at the C5/6/7 level:

a The spinal canal can still be assessed despite the artifacts.

The extent of the artifact effect depends on the sequences selected and, particularly in the axial sequences, can have considerable influence (b, c) or hardly any at all (d, e).

Operative technique of anterior operations on the cervical spine

Since most pathological changes associated with degenerative disorders of the cervical spine lie anterior to the spinal cord and nerve roots, an anterior procedure is more efficient and less hazardous than a posterior operation in the vast majority of cases. Nearly every patient dreads the risk of spinal cord paralysis during surgery, an unjustified fear given the performance statistics from experienced surgeons. Even in extreme spinal stenosis, deterioration secondary to surgery is exceedingly rare provided the correct operative technique is used, and when it does occur then obvious risk factors are most likely involved (angiopathy, cardiopulmonary decompensation).

A transverse median skin incision is placed two-thirds off midline towards the side of the operative site. The side of approach is often merely a question of the surgeon’s handedness rather than one of, for example, the location of the prolapse. After dividing the platysma longitudinally, blunt dissection is carried down, displacing the trachea and esophagus medially (take care: there is risk of injury; watch for air collections after surgery as an indication of infection secondary to perforation) while the neurovascular bundle (carotid artery, jugular vein, vagus nerve) is displaced laterally. After division of the deep cervical fascia, access is gained to the anterior aspect of the cervical spine; the longus colli muscle is detached on either side and then the actual procedure on the cervical spine is performed:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree