Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become an important part of the work-up of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancers. Although no large studies have proved a survival advantage, and questions remain as to whether preoperative MRI has reduced re-excision and recurrence rates, the potential benefit of preoperative MRI cannot be questioned. MRI can identify foci of invasive disease with greater sensitivity than mammography or sonography, allowing identification of multicentric and multifocal disease that would otherwise go undetected. Identifying these additional foci may lead to a more extensive lumpectomy than originally planned, or even mastectomy. MRI may also demonstrate axillary lymphadenopathy and chest wall invasion, which can have an impact on surgical management. MRI is also the most accurate modality for monitoring patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Ductal carcinoma makes up about 85% of all breast cancers. Invasive lobular carcinoma constitutes another 5% to 15%. Special types of breast cancer and sarcoma make up the remainder. These include tubular, medullary, and mucinous carcinomas. Inflammatory carcinoma does not represent a distinct histologic subtype of breast carcinoma, but it is distinguished by its clinical presentation and because its treatment differs from that of other breast cancers. Recognition of these special types of breast cancer may have implications in the management of breast cancer. The mammographic and sonographic features of these special types of breast cancer have been well characterized, but their MRI features are not as widely known. MRI may allow more accurate distinction of the various types of breast cancer than that provided by conventional imaging because it adds physiologic information. This chapter discusses the MRI features of several special types of breast cancer.

MRI of Invasive Lobular Carcinoma

Invasive lobular carcinoma constitutes 5% to 15% of breast cancers. It is characterized by an insidious growth pattern, with uniform, small, round tumor cells, typically infiltrating in single file. This growth pattern is probably the result of a lack of e-cadherin expression, a gene involved in cell-cell cohesion. Lack of e-cadherin expression is one way that invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is differentiated histologically from invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). ILC does not cause a significant desmoplastic reaction and is less commonly associated with calcifications than is IDC. As such, ILC is typically harder to detect during a physical exam, being more likely to present as palpable thickening or skin or nipple retraction than as a discrete palpable mass.

On mammography, lobular carcinoma tends to be iso- or hypodense to breast tissue, limiting its visibility. Although the most common presentation on mammography is a spiculated or ill-defined mass, it is more likely than IDC to present as an asymmetry or architectural distortion. Round or circumscribed masses are uncommon, seen in only 1% to 3% of cases. It is not uncommon for findings to be present on one view only, most commonly the craniocaudal view because of its better compression. Another characteristic finding on mammography is that of a “shrinking” breast. It is thought that the sheet-like infiltrating pattern of the tumor reduces the breast’s natural elasticity, allowing for less spreading of the tissue during mammographic compression. Clinically, however, the breast may remain symmetric in size with respect to the other side. Microcalcifications also are uncommon, being reported in 1% to 28% of cases, presumably owing to the absence of associated ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

These factors all contribute to a decreased sensitivity of mammography, and ILC is a well-known cause of false-negative mammography results. The reported sensitivity of mammography ranges from 34% to 92%. But even when mammography detects tumors, it tends to underestimate their size.

Ultrasound has a higher sensitivity for ILC than mammography, ranging from 68% to 98%. Imaged by ultrasound, ILC most commonly appears as an irregular, hypoechoic mass with ill-defined or spiculated margins and associated acoustic shadowing. The tumor may also appear as shadowing without a discrete mass because of the sheet-like infiltrative nature of the tumor.

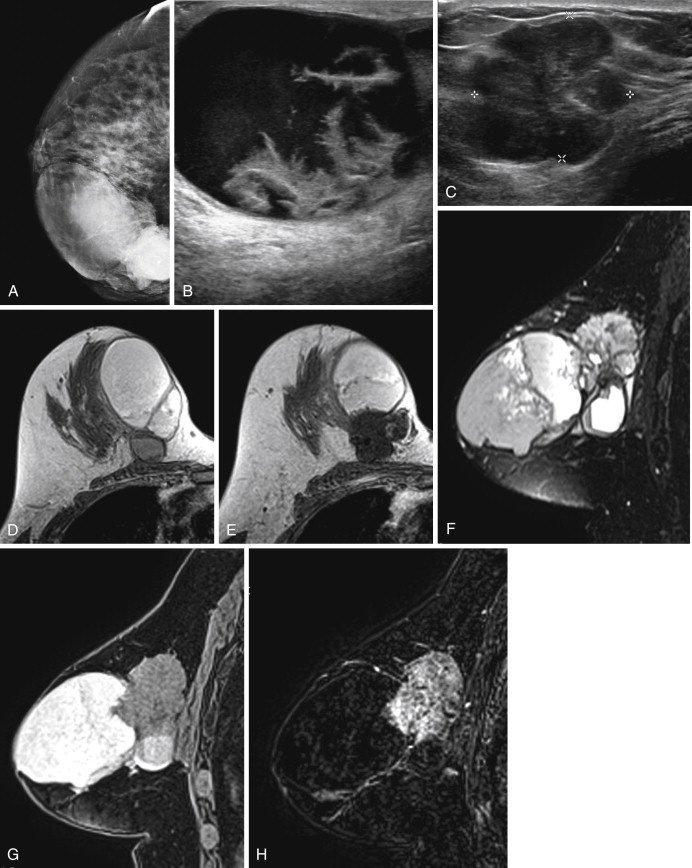

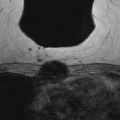

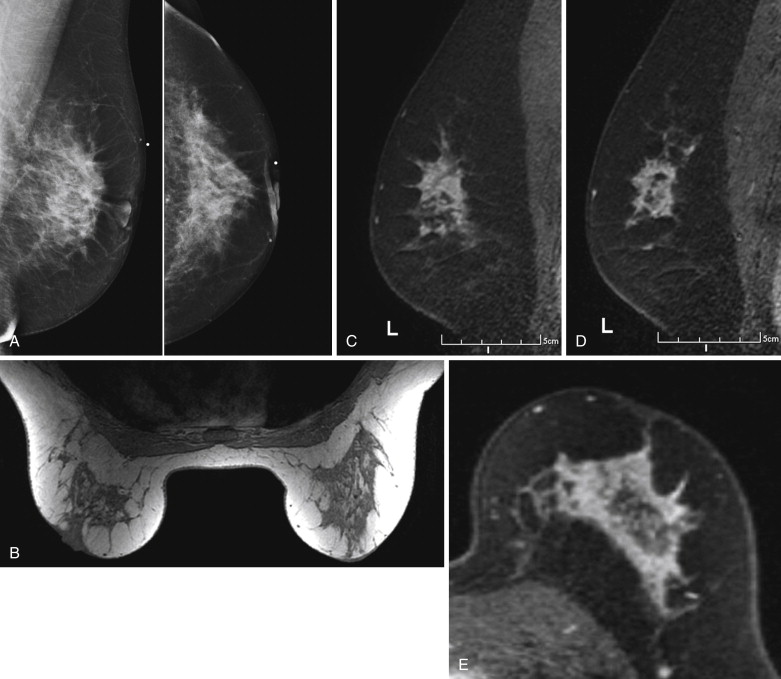

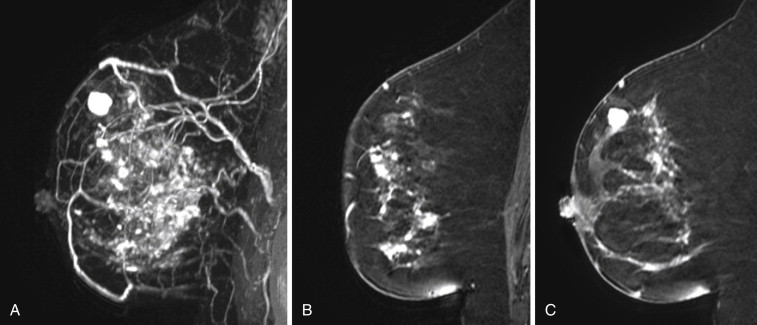

Because it can be more difficult to detect both clinically and on imaging than other cancers, ILC is more frequently locally advanced at diagnosis and is generally a larger tumor at the time of presentation than is IDC. It also has a higher incidence of multifocality and multicentricity than does IDC. Patients with ILC are more likely to have positive surgical margins after lumpectomy, and although ILC often manifests with larger tumors, overall patient survival is similar to or slightly better than that of patients with IDC. Despite its more infiltrative growth pattern, ILC is very similar to IDC in its MRI appearance ( Figure 6.1 through Figure 6.5 ). The most common MRI presentation is an irregularly shaped mass with irregular or spiculated margins. Round masses are rarely described: In a meta-analysis by Mann and colleagues, only 1 out of 143 masses was described as round. Absence of smooth margins was a feature found to be significantly associated with ILC by Stivalet and coworkers ; however, a study by Levrini and colleagues found smooth margins in 5 of 13 masses. Mass internal enhancement is most often described as heterogeneous. Two studies comparing the morphologic features of ILC with those of IDC on MRI found no significant difference in the distribution of morphologic descriptors between the two.

Some investigators have described a stranding pattern of tumor enhancement associated with ILC. Qayyum and coworkers described a pattern of multiple, small, enhancing foci with or without interconnecting enhancing strands. This pattern was seen in 62% of their cases and correlated with the histopathologic finding of tumor clusters separated by either normal breast tissue or tumor cells infiltrating in single file between more nodular tumor foci. In 8%, enhancing septa were seen without a dominant focus. A similar pattern of multiple small enhancing foci separated by enhancing strands was reported in a later study by Schelfout and colleagues and seen in 12% of cases. This pattern is concordant with the single file and sheetlike pattern of infiltrative growth seen with ILC. Another common pattern described by Schelfout was a dominant lesion surrounded by multiple small enhancing foci.

In terms of kinetic features, two early studies reported a later peak enhancement for ILC cases with wash-out seen only in a minority of cases. In a later study by Dietzel and coworkers again comparing IDC to ILC, almost all ILCs and IDCs showed intermediate or strong wash-in, but delayed phase wash-out was more common with IDC, present in 72.6% of IDC cases versus 57.4% of ILC cases. Mann and colleagues also compared enhancement kinetics between ILC and IDC. They found that the maximum relative enhancement and the fraction of voxels that showed rapid enhancement were similar between the two groups. However, in the ILC group, a smaller proportion of the tumor showed delayed phase wash-out curves than in the IDC group, and a larger proportion of the tumor showed persistent delayed phase curves. Accordingly, when visual inspection, rather than computer-aided detection (CAD), was used to assess kinetics, wash-out was more frequently seen, but involved a smaller proportion of the tumor in ILC than in IDC. They concluded that ILC enhances slower than IDC, reaching peak enhancement later, but there is no significant difference in the peak enhancement.

ILC has a greater propensity to be multifocal or multicentric than IDC (see Figure 6.5 ). Additionally, it can be difficult to detect on conventional imaging. These factors make MRI an indispensable tool in preoperative assessment of ILC. As previously discussed, MRI more accurately determines tumor size in lobular carcinoma than does mammography. In a meta-analysis by Mann and coworkers, additional ipsilateral malignant lesions were detected only on MRI in 32% of patients with histologically proven ILC. Overall, MRI findings changed management in 28% of cases. In another study of 57 patients with ILC, MRI changed management in 49%, resulting in more extensive surgery in 40% and less extensive surgery in 9%. In a larger study of 267 patients with ILC, investigators reported reduced reexcision rates in patients undergoing breast conservation therapy with preoperative MRI (9%) compared to re-excision rates in those with no preoperative MRI (27%).

Mucinous Carcinoma

Mucinous carcinoma of the breast is an uncommon variety of breast cancer accounting for 1% to 7% of all breast cancers and typically seen in an older age group. Its characteristic feature is production of abundant extracellular mucin, resulting in a histologic appearance of islands of tumor cells floating on pools of mucin. However, the tumor can frequently have a mixed histologic pattern, with variable amounts and distribution of IDC NOS (not otherwise specified). In these cases the tumor is described as mixed mucinous carcinoma . The term pure mucinous carcinoma is used when less than 10% of the tumor is made up of IDC.

The distinction between pure mucinous carcinoma and mixed mucinous carcinoma is important because pure mucinous carcinoma has a lower likelihood of axillary lymph node metastases and an overall better prognosis than the mixed type. The 10-year survival rate for pure mucinous carcinoma ranges from 87% to 90.4%, and that for mixed mucinous carcinoma ranges from 54% to 66%.

The imaging features of mucinous carcinoma depend on the amount of extracellular mucin present and whether it is pure or mixed with IDC NOS. Pure mucinous carcinomas with abundant extracellular mucin are more likely to appear on mammography as a mass with circumscribed or microlobulated margins, whereas mixed tumors usually have indistinct or spiculated margins. Calcifications are uncommon. On ultrasound, mucinous carcinomas may be isoechoic or hypoechoic. Complex mixed cystic and solid masses are frequent. There may be associated acoustic enhancement. This finding is more commonly seen in tumors with abundant mucin.

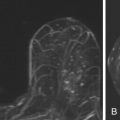

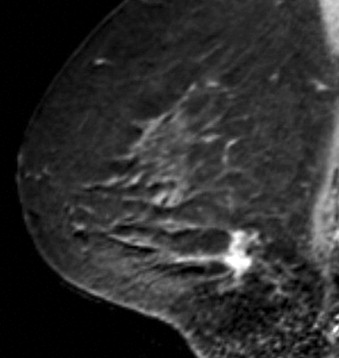

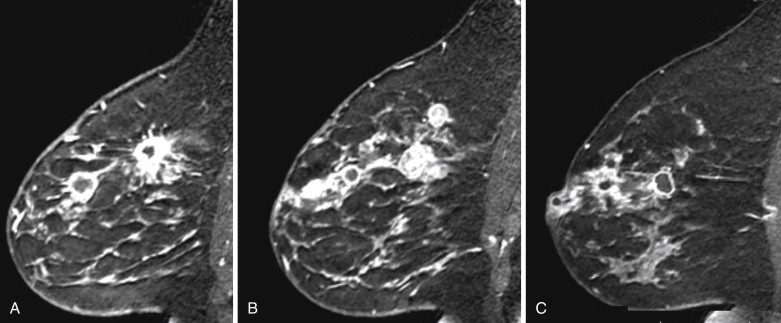

Several studies have described the MRI features of mucinous carcinoma. The most characteristic MRI feature of mucinous carcinoma is high T2 signal intensity caused by the high water content of the mucin ( Figure 6.6 ). The tumor may contain areas of iso-intense T2 signal related to fibrous septations and bands or related to areas hemorrhage and necrosis. More solid components of the tumor may also show lower T2 signal intensity. The predominant lesion type is a mass. Mass shape is most frequently lobular and less often round or oval. Mass margins are most frequently smooth but can be irregular.

The internal enhancement pattern depends on the distribution of the cellular elements. A rim enhancement pattern is frequently seen and has been attributed to a peripheral distribution of cellular elements. Otherwise, internal enhancement tends to be heterogeneous and can be attributed to the heterogeneous distribution of cellular elements and mucin in the tumor. Dark internal septations have been described related to thick fibrous septa.

Another typical feature of mucinous carcinoma on MRI is slow or persistent enhancement kinetics. This is due to the longer time it takes for contrast to diffuse through the mucin compared with its diffusion in more cellular tumors or in tumors with more fibrous stroma. Rapid enhancement with wash-out can also be seen, although this is less common. In one study, tumors with higher cellular grade tended to have stronger enhancement, and lower-grade tumors tended to have mild enhancement.

On diffusion-weighted imaging, the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) of pure mucinous tumors has been shown to be higher than that of IDC NOS and that of benign tissues. This is not surprising in light of the generally low cellularity and mucin content of pure mucinous carcinomas. Woodhams and colleagues found that mixed mucinous carcinomas had ADC values between those of IDC and pure mucinous carcinomas, although there were only two cases of mixed mucinous carcinoma in that study. Hatakenaka found a significant difference between the ADCs of mucinous tumors and ADCs of fibroadenomas, which is important because other MRI features, such as high T2 signal and tendency toward persistent enhancement, can be similar between mucinous tumors and fibroadenomas. Thus diffusion-weighted imaging may aid in imaging differentiation between benign fibroadenomas and mucinous carcinomas.

Medullary Carcinoma

Medullary carcinoma is rare, accounting for 5% to 7% of all breast cancers. It has an increased incidence in young women, making up 11% of breast cancers in women receiving the diagnosis of breast cancer at age 35 or younger. It also has an increased incidence in women who are breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility ( BRCA1)- gene–positive. True medullary carcinoma has a better prognosis than invasive ductal carcinoma, having a 10-year survival rate of 92%.

The World Health Organization criteria for the histologic diagnosis of medullary carcinoma includes “syncytial growth pattern (>75%), diffuse moderate to marked lymphocytoplasmacytic infiltrate, moderate to marked nuclear pleomorphism, and complete histologic circumscription.” Medullary carcinoma does not infiltrate the surrounding tissues, growing with a “pushing” margin, sometimes with encapsulation, resulting in a tumor with a circumscribed appearance histologically. At gross evaluation, its features can mimic those of a fibroadenoma. There is no glandular structure and scant stroma is present. Lymphocytoplasmacytic infiltrate is a prominent feature, and can be within the tumor or in its surroundings. The tumor is often quite large at presentation.

Lesions that exhibit some, but not all of these features were formerly considered to be atypical medullary carcinomas. Now these tumors are referred to as IDC with medullary features. The histologic differentiation between typical medullary carcinoma and IDC with medullary features is important because these atypical tumors do not exhibit the same good prognosis.

The mammographic and sonographic features of medullary carcinoma can also mimic those of fibroadenomas. On mammography, medullary carcinoma usually appears as a noncalcified mass, frequently of high density, with circumscribed, indistinct, or obscured margins. On ultrasound, medullary carcinomas present as hypoechoic masses associated with acoustic enhancement, shadowing, or no posterior acoustic features. Margins may be lobular, circumscribed, or indistinct but tend not to be spiculated. In comparison with IDC with medullary features, typical medullary carcinoma is more frequently seen as a circumscribed mass on mammography. In one study, two thirds of typical medullary carcinomas had circumscribed margins and the remainder had partially indistinct margins. Only 1 of 15 typical medullary carcinomas contained calcifications compared with 4 of 17 cases of IDC with medullary features.

By histologic definition, medullary carcinoma is a circumscribed mass. However, on imaging, it frequently presents with indistinct margins. This has been attributed to surrounding lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates.

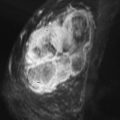

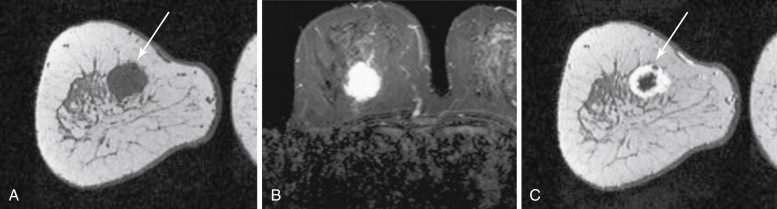

Two studies have specifically described the MRI appearance of medullary carcinoma. Tominaga and colleagues compared the MRI findings in eight cases of medullary carcinoma with their histopathologic appearance. All eight cases were masses with lobular shape and smooth margins. All were iso-intense on precontrast T1-weighted images and iso- or slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted images. All showed plateau or wash-out kinetic curves. The tumors all showed peripheral enhancement in the late phase, which the authors thought suggested prominent surrounding inflammatory changes. Four tumors had homogeneous internal enhancement, all of which had a uniform distribution of tumor cells without necrosis. Four lesions had heterogenous internal enhancement with “small non-enhanced spots” ( Figure 6.7 ). All of these tumors had necrotic areas.

More recently, Jeong and coworkers described the MRI features of 15 medullary carcinomas. All 15 lesions were masses on MRI. Two were irregular masses with irregular margins, and the rest were oval or lobular masses with smooth margins. All lesions were iso- or hypointense on precontrast T1-weighted images, and iso- or hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Thirteen of 15 lesions showed rim enhancement with or without internal septations. Internal septations on MRI correlated with fibroepithelial septations at histology. Nine of 15 lesions showed a hypointense rim on T2-weighted images. The authors believe that this might have been caused by a peripheral fibrous capsule. At histology, the two irregular masses had intense lymphocytic reaction or secondary nodules around the tumor, causing the appearance of a microlobulated border.

Papillary Carcinoma

Papillary lesions of the breast represent a family of lesions that have in common a frondlike growth pattern with epithelium supported by a fibro-vascular stroma. Papillary lesions of the breast include benign papillomas, papillary DCIS, and papillary carcinoma. The presence or absence of myoepithelial cells lining the basement membrane of the frondlike projections differentiates benign papillomas, in which they are present, from papillary carcinoma, in which they are absent.

Papillary carcinoma can be invasive or noninvasive. The noninvasive forms were previously described as intracystic or intraductal, depending on whether a cystic component was identified. However, the “cystic” form likely represents an intraductal lesion growing within an obstructed and cystically dilated duct. In both cases, there is a central mass encased by a thickened fibrous wall. The term encapsulated papillary carcinoma is now favored to describe both lesion types. Classically, the fibrous wall contains myoepithelial cells, supporting the classification as a noninvasive lesion. However, myoepithelial cells may be absent in a large proportion (in 85% of cases), leading some investigators to consider these lesions to be indolent invasive lesions. Special stains such as p63, calponin, smooth muscle actin, and CD10 can be used to assess for the presence or absence of myoepithelial cells. There can be associated foci of typical invasive carcinoma, usually ductal carcinoma. These are most commonly located at the periphery of the lesion and can also infiltrate beyond the fibrous capsule.

The imaging features of papillary lesions reflect the intraductal nature of the lesion. These lesions commonly present as a retro-areolar round, oval, or lobulated mass. Mammographically, the mass margins may be circumscribed or indistinct. Spiculation is uncommon. There may be associated clustered calcifications. On ultrasound, single or multiple masses may be seen. Masses are usually hypoechoic and may be solid or complex, with a cystic component. Masses commonly show posterior acoustic enhancement. The imaging features of papillary carcinoma overlap with those of benign papillomas and there are no imaging features that can reliably differentiate between benign and malignant papillary lesions. Hemorrhage is a frequent feature of papillary lesions and may be caused by torsion of the stalk and infarction of the solid components. This can lead to hemorrhage within the cyst fluid. The fibrovascular core may contain large vessels that may be apparent on Doppler ultrasound.

Clinically, papillary carcinomas are rare, accounting for fewer than 2% of all breast carcinomas. They typically occur in an older patient population than the typical patient population with ductal carcinomas. Patients commonly present with bloody nipple discharge, which is present in 5% to 25%.

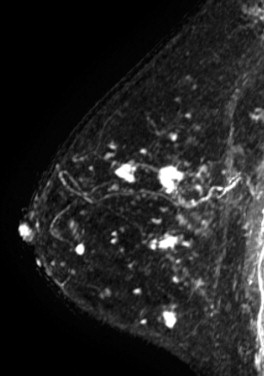

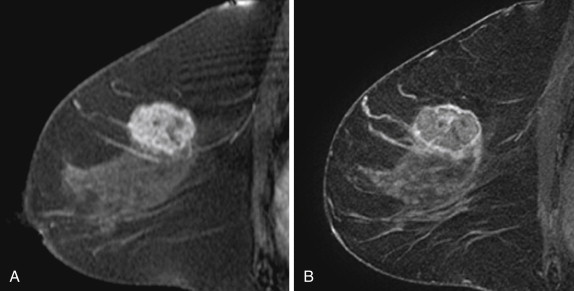

The literature regarding the MRI appearance of papillary carcinoma is scant and generally limited to case reports. A multi-cystic appearance with marked enhancement of the cyst wall, intralesion septations, and mural nodules has been described, as well as intracystic hemorrhage causing fluid-fluid levels on precontrast images ( Figure 6.8 ). Multifocal areas of high precontrast T1 signal owing to hemorrhage have also been described. The largest series was reported by Linda and colleagues and included eight cases of intracystic and intraductal papillary carcinoma and five cases of invasive papillary carcinoma. They found that the morphologic and kinetic features of papillary carcinoma were somewhat variable. Three of four intracystic tumors were detectable on MRI as round or oval masses with well-defined borders. Intraductal papillary carcinomas were more likely to be seen as irregular masses, with two of four described as irregular in shape, and one described as dendritic in shape. No intracystic or intraductal tumors had wash-out, and out of all eight intracystic or intraductal lesions, only one case showed more than 100% enhancement in the first postcontrast minute. Invasive papillary carcinomas were also more likely to appear as irregular or dendritic masses, and three of four lesions detectable with MRI had ill-defined borders. Three of four detectable invasive papillary carcinomas had greater than 100% early enhancement and three of four had wash-out. Invasive papillary carcinomas were also more likely to show inhomogeneous internal enhancement or rim enhancement than intraductal or intracystic lesions.