Some benign pathologic entities of the breast, when diagnosed at image-guided core needle biopsies, have the potential to be upgraded to invasive carcinoma or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) upon complete excision by surgery. These entities are collectively categorized as high-risk lesions and include atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), flat epithelial atypia (FEA), atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH), lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), papillary lesions, radial scar, phyllodes tumor, and mucocele-like lesions. This chapter describes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features of these lesions.

Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia

ADH defines a group of epithelial proliferative lesions that have some, but not all, of the features of DCIS, either by lack of a major defining cytologic feature of carcinoma or by having the features to a lesser extent than true DCIS (i.e., involvement of a single duct and size of less than 2 mm in diameter) The most common types of ADH architecture are the cribriform and micropapillary patterns. The average age of women with ADH is late 40s. ADH is associated with a 4 to 5 times relative risk of development of breast cancer within 10 to 15 years after breast biopsy. The absolute risk of developing cancer in women with ADH after age 40 to 45 years is about 10% in the ensuing 15 years. The risk of cancer is at any site and in either breast.

ADH is clinically occult, usually detected on screening mammograms as suspicious microcalcifications. With the extensive use of screening mammography, there has been a significant increase in the diagnosis of ADH. It is found in approximately 10% of screen-directed biopsies. There are no reported characteristic features of ADH on sonography.

No studies to date show definitive and specific characteristics of ADH on MRI. According to published data by Liberman and colleagues, ADH may appear as masses or areas of nonmasslike enhancement. Figure 8.1 illustrates ADH presenting as a mass, and Figure 8.2 shows ADH, coexisting with flat epithelial atypia (FEA), as extensive nonmasslike enhancement in ductal and segmental distributions.

Distinction between ADH and DCIS on histopathology can be difficult. It is even more challenging on core needle biopsy samples because of fragmentation and the limited quantity of tissue. A study of the published data by Heller and Moy showed ADH to be the most common high-risk lesion detected on MRI and to have the highest upgrade rate to carcinoma on subsequent excision among all high-risk lesions. The reported rates of underestimation of malignancy of ADH (upgrade rates) are highly variable, ranging from 16% to 50%. Given the high upgrade rate, it has long been established that a diagnosis of ADH on core needle biopsy warrants surgical excision.

Flat Epithelial Atypia (Columnar Cell Changes/Hyperplasia with Atypia)

Columnar cell changes refer to a condition in which the normal epithelial cell layer of the terminal ductal tubular unit (TDLU) is replaced by one or two layers of taller columnar epithelial cells that have basal nuclei and apical cytoplasmic snouts. When these columnar cells show cellular stratification with more than two cell layers, the entity is described as columnar cell hyperplasia. Columnar cell change with atypia and columnar cell hyperplasia with atypia are collectively referred to as flat epithelial atypia (FEA). The number of FEA cases diagnosed is increasing because of advances in breast imaging and increasing use of core needle biopsy. FEA is usually diagnosed in premenopausal women between the ages of 35 and 50 years. However, the incidence of FEA is not well established.

FEA is a clinically silent entity that often appears as suspicious microcalcifications on mammography. When visible on sonography, FEA lesions appear most often as masses with irregular shapes, microlobulated margins, and hypoechoic or complex echotexture. No MRI features specific to FEA have been reported. Figure 8.3 illustrates a case of biopsy-proved FEA appearing as a small mass. Figure 8.4 is a case of FEA associated with ADH presenting as clumped nonmasslike enhancement in a segmental distribution on a background of fibrocystic changes.

FEA is frequently associated with low-grade DCIS, invasive tubular carcinoma, lobular neoplasia (i.e., ALH, LCIS), and invasive lobular carcinoma. The “Rosen triad” describes the association of columnar cell lesion, tubular carcinoma, and lobular neoplasia. FEA shows some genetic similarities to low-grade DCIS and invasive carcinoma. It appears likely that FEA may represent a precursor lesion of, or risk factor for low-grade DCIS or invasive carcinoma. Several studies showed that FEA diagnosed by core needle biopsy was upgraded to DCIS or invasive carcinoma on subsequent surgical excision in 14% to 21% of cases. However, Piubello and associates reported 0% upgrade rate in 20 cases of pure FEA on surgical excision in their series and suggested that FEA diagnosed by 11 gauge vacuum-assisted core needle biopsy may be managed with close imaging follow-up without surgery. Although more research is needed to determine the optimal clinical management of FEA, it is prudent to consider surgical excision when imaging-guided needle biopsy yields pure FEA, given the reported upgrade rates.

Lobular Neoplasia

ALH and LCIS are relatively uncommon lesions, collectively identified as lobular neoplasia. Both entities have identical cytologic features, consisting of round, small cells with increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, and are defined histologically by differing degrees of involvement and distention of acini in the terminal ductal lobular unit (TDLU). The true incidence of lobular neoplasia is unknown but estimated to be 1% to 3.6%. It is most commonly found in premenopausal women, with a mean age of 44 to 46 years. Lobular neoplasia is often multicentric (approximately 50% of cases) and bilateral in up to 30% of cases. These lesions are considered to be generalized risk factors for subsequent breast cancer, with a relative risk of 4 to 5 times for ALH and 8 to 10 times for LCIS. Current and ongoing epidemiologic and molecular studies support the notion that lobular neoplasias may also be precursor lesions.

Lobular neoplasia is clinically silent. Although it was previously regarded as an incidental finding on a biopsy performed for other reasons, recent reports show most of these lesions to be visible on imaging, albeit with nonspecific features. Destounis and coworkers reported that 54 of 64 biopsy-proven cases of LCIS were visible mammographically, appearing as microcalcifications, focal asymmetries, architectural distortions with or without calcifications, or masses with or without calcifications. Microcalcifications have been observed near or within involved TDLUs. There is no report of specific ultrasonographic features of lobular neoplasia.

To date, there are no reports that describe specific characteristics of lobular neoplasia on breast MRI. Experience at our institution shows that they may appear as nonmasslike enhancement ( Figure 8.5 ), a focus ( Figure 8.6 ), or a mass ( Figure 8.7 ). When appearing as a mass, the enhancement kinetics are medium or rapid in the early phase, and mixed persistent, plateau, and washout kinetics in late phase.

Lobular neoplasia is second to ADH in terms of incidence among high-risk lesions. In a large series, Brem and colleagues reported upgrade rates to malignancy of 23% for lobular neoplasia diagnosed on core needle biopsy (25% for LCIS and 22% for ALH). Four other smaller series reported upgrade rates for lobular neoplasia ranging from 19% (Mahoney et al.) to 50% (Crystal et al.). Although there is some controversy, surgical excision is usually recommended after a diagnosis of lobular neoplasia on core needle biopsies. This is especially true in the cases of mammographically detected lesions or variants of LCIS such as pleomorphic LCIS and LCIS with central necrosis, both of which have more aggressive behaviors than usual LCIS. There are divergent views regarding the appropriate treatment of patients in whom lobular neoplasia has been diagnosed. Management options include increased surveillance with physical examination, mammography, and MRI, as well as chemoprevention with female hormone antagonists such as Tamoxifen and Raloxifene. Bilateral mastectomy may be considered for women with a very strong family history of breast cancer or a breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility ( BRCA ) gene mutation.

Papillary Lesions

Papillary lesions of the breast may be classified as solitary intraductal papillomas, multiple intraductal (peripheral) papillomas, atypia-DCIS within a papilloma, micropapillary DCIS, and papillary carcinoma. Benign papillary lesions include solitary and multiple intraductal papillomas and papillomas with atypia. A distinction must be made between multiple intraductal papillomas and intraductal papillomatosis. Intraductal papillomatosis is used to describe microscopic ductal hyperplasia.

Papillomas are benign ductal neoplastic lesions composed of arborizing fronds of fibrovascular stroma with a stalk, covered with proliferative ductal epithelium and myoepithelial cells. They may be solitary or multiple and are usually found in perimenopausal women, although they have been increasingly diagnosed in younger asymptomatic patients because of the widespread use of screening mammography and breast ultrasound.

Solitary Intraductal Papilloma

Solitary papillomas are usually found centrally in the subareolar major lactiferous duct and cause bloody or serous nipple discharge when symptomatic. They are often nonpalpable but may appear as a palpable mass when large. They range from 3 to 5 mm to several centimeters in size.

Papillomas may be so small as to be mammographically occult. They may also be seen as a circumscribed mass or dilated duct or as microcalcifications. Sonographically, they may appear as a smooth hypoechoic mass within an ectatic duct or as a complex mass with a solid component. Color Doppler imaging may show the mass arising from a vascular feeding pedicle.

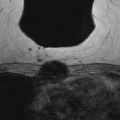

There are a few reports on the MRI appearance of papilloma. On MRI, papillomas may appear as a mass with smooth or irregular margins, often associated with a dilated duct, or they may appear as a complex cystic and solid mass. Summarized from the reports of Tominaga, Bhattarai, and Kurz and colleagues, the three most common features suggestive of papillomas are retroareolar location, homogeneous enhancement, and a dilated duct. Bhattarai and coworkers found the associated dilated ducts to show T1 and T2 signal hyperintensity, likely owing to hemorrhage and mixed-age blood products. Tominaga and colleagues observed that irregular papillomas completely filled the ductal lumen and were surrounded by fibrosis of the periductal fibroglandular tissue.

Papillomas are isointense in signal to fibroglandular tissue on T1-weighted precontrast images. They are iso- to slightly hyperintense on fat-suppressed T2-weighted images. The intraductal mass may be obscured by ductal contents on T2-weighted images ( Figure 8.8 ). Papillomas enhance avidly and rapidly, with variable persistent, plateau, or washout kinetics in the delayed phase. Washout kinetics are less common, but not rare, making differentiation from malignancy impossible without biopsy. There are no reported definitive MRI morphologic or kinetic features that predict upgrade of papillomas to malignancy.

Multiple Intraductal Papillomas

Multiple intraductal papillomas arise from the TDLU and are usually peripherally located. Therefore the condition is also named multiple peripheral papillomatosis . Except for their multiplicity and origination from TDLU, they have the same features as solitary papillomas on breast MRI ( Figure 8.9 ).

The diagnosis of intraductal papilloma is associated with an increased risk of developing breast carcinoma relative to the general population. The risk is higher (up to threefold) with multiple peripheral papillomas and extends equally to both breasts.

Juvenile Papillomatosis

Juvenile papillomatosis is an entity first described by Rosen and colleagues in 1980 in a group of adolescents and young women with a constellation of changes usually described as components of fibrocystic disease. This hereditary condition carries a slightly increased risk for malignancy. It may be a marker for families at risk for breast cancer, because 28% to 33% of affected women have a family history of breast carcinoma. With further follow-up, the frequency of positive family history exceeds 50%. “The female relatives of patients most likely to be affected by breast carcinoma are their mothers and maternal aunts.”

Summary

The presence of atypia in a papilloma confers a relative breast cancer risk 7.5 times that of a papilloma without atypia. A papilloma with atypia is associated with malignancy in as many as 67% of cases. There is consensus that papillomas with atypia diagnosed on core needle biopsy should be surgically excised. The need for surgical excision of papillomas without atypia is controversial. There are reported upgrade rates of papilloma as low as 3%, which some authors have used to support mammographic follow-up over surgical excision. However, because of the focal nature of atypia in papillary lesions and the frequent fragmentation on tissue samples, some recent studies recommend surgical excision, showing upgrade rates of up to 29% for papillary lesions thought to be benign at initial core biopsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree