Malignant Mucosal Processes

Etiology

A wide range of benign disease processes can affect the mucosa of the stomach, including inflammatory, infectious, hereditary, and autoimmune processes. What these processes have in common is that they affect one of the primary defenses of the stomach wall—the mucosal layer.

In considering the radiologic appearance of these entities, it is helpful to divide them into their primary mucosal manifestations—ulcers, polyps and masses, and diffuse mucosal processes. Some of the more common processes include the following:

- •

Ulcers: Infections ( Helicobacter pylori, cytomegalovirus), erosive gastritis (nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], alcohol, stress, radiation, direct trauma), Crohn’s disease, autoimmune (Behçet’s) disease, sarcoidosis

- •

Polyps and masses: Hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps (also seen in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome and familial polyposis of the colon), hamartomas (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Cowden’s disease), heterotopic pancreatic tissue, lymphoid hyperplasia

- •

Diffuse mucosal processes: Acute gastritis, atrophic gastritis, eosinophilic and lymphocytic gastritis, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, Ménétrier’s disease, and those that cause a linitis plastica appearance (corrosives, radiation, Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, syphilis)

In this chapter, the discussion is tailored to each of these categories, with a description of the most common entities.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Benign Diseases Causing Mucosal Ulcerations

The most common benign cause of mucosal ulcerations is peptic ulcer disease. Although decreasing in overall incidence with the routine use of histamine-2 (H 2 ) blockers, the overall death rate from peptic ulcer disease has remained stable. The vast majority of cases of gastric ulcers (70% to 90%) and duodenal ulcers (up to 90%) are due to H. pylori infection.

Other causes of gastric ulcers include NSAIDs and aspirin. Chronic NSAID users have a prevalence of peptic ulcer disease of 25%. Less common causes of benign gastric mucosal ulcers include stress ulcers in burn patients (Curling’s ulcers) and head trauma patients (Cushing’s ulcer), crack cocaine and alcohol abuse, Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis, cytomegalovirus infection, and Behçet’s disease.

Benign Diseases Causing Polyps and Masses

Polypoid lesions of the stomach include hyperplastic (regenerative), adenomatous, hamartomatous, and inflammatory polyps, as well as heterotopic pancreatic tissue. The most common benign polyps are hyperplastic polyps, which can commonly occur in the setting of gastritis. Unlike adenomatous polyps, which can degenerate in a fashion similar to that of colonic adenomas, hyperplastic polyps have almost no malignant potential.

Hamartomatous polyposis syndromes are rare and include Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, multiple hamartoma/Cowden’s disease, juvenile polyposis, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. Whereas hamartomatous polyps are themselves without malignant potential, they are frequently associated with adenomatous polyps. More importantly, these syndromes can be associated with extraintestinal malignancies, and diagnosis is essential so the patient can be undergo screening.

Benign Diseases Causing Diffuse Mucosal Abnormalities

The most common diseases that affect the gastric mucosa diffusely are acute gastritis and chronic and atrophic gastritis. Acute gastritis, most commonly secondary to H. pylori infection, can progress to a chronic state if left untreated. Other causes of acute gastritis include NSAID-induced gastritis, caustic ingestion, and granulomatous disease (sarcoidosis, tuberculosis), as well as less common causes such as cytomegalovirus infection, herpesvirus infection, and syphilis.

Chronic gastritis can progress to atrophic gastritis, which is characterized by loss of the normal mucosal glands and is categorized by the portion of the stomach involved. Type A chronic and atrophic gastritis, which affects predominantly the fundus and body, has been termed autoimmune gastritis and is the least common of the two types. This form is associated with pernicious anemia, caused by destruction of the parietal cells and loss of intrinsic factor, which leads to vitamin B 12 deficiency and megaloblastic anemia. More common is type B chronic/atrophic gastritis, which affects predominantly the antrum and is associated with chronic H. pylori infection.

Other causes of gastritis are less common. Eosinophilic gastritis is characterized by blood eosinophilia and eosinophilic gastric wall infiltrates. The antrum is predominantly involved, and mucosal fold thickening can become severe enough to cause gastric outlet obstruction. Bowel involvement can occur and is termed eosinophilic gastroenteritis .

Diffuse gastric fold thickening can occur as a result of inflammation or infiltration. In Ménétrier’s disease there is hypertrophy of the mucus-producing cells of the stomach mucosa, causing marked fold thickening. This rare disorder is of unknown cause and can mimic malignancy as well as severe gastritis or an infiltrative process. In addition to the usual clinical presentation of pain, weight loss, and occasional bleeding, the disorder is characterized by hypoalbuminemia secondary to loss of proteins.

Pathology

In general, entities that affect the stomach mucosa can be divided into a few broad categories: infectious, inflammatory, infiltrative, autoimmune, and hereditary. Those processes causing ulcers can fall into any of these categories, but polypoid lesions tend to represent either inflammatory or hereditary causes.

Infectious causes, including most commonly H. pylori, all begin by circumventing the stomach mucosa’s natural defenses. Because of its highly acidic environment, the stomach is able to withstand infection from a wide range of ingested bacteria. However, in H. pylori, the bacteria have adapted mechanisms to neutralize the acidic environment by creating sodium bicarbonate and ammonia from the enzyme urease. Once it has colonized the stomach, H. pylori causes an increase in gastric acid production through a variety of mechanisms, including inhibition of the production of somatostatin by the antral D cells. Because somatostatin is a potent inhibitor of antral G cell gastrin production, this leads to an overall increase in acid secretion. This acid hypersecretion is thought to be the primary mechanism for H. pylori —induced gastritis and ulcer formation.

Other infectious agents, including herpesvirus and cytomegalovirus, involve direct viral infection of the mucosal cells. Clinically, these affect immunocompromised patients. Cytomegalovirus infection is characterized by intranuclear inclusions seen on biopsy. Syphilitic involvement of the stomach is rare but has been seen with increasing frequency in immunocompromised patients. In early disease, gastritis is characterized pathologically by perivascular and mucosal mononuclear infiltration. In later stages of the disease, gummatous involvement of the stomach can occur, as well as scarring and stricture.

Inflammatory causes of gastritis include NSAID-induced gastritis, as well as caustic ingestion. The most common of these disorders is NSAID-induced gastritis. NSAIDs cause a decrease in stomach mucus and bicarbonate production by inhibiting prostaglandins. This leads to a breakdown in the defensive barrier of the stomach lining to gastric acid, which in turn leads to gastritis and ulcer disease.

Infiltrative causes tend to result in a diffuse abnormality of the stomach mucosa. These include eosinophilic and lymphocytic gastritis, Ménétrier’s disease, sarcoidosis, and tuberculosis. The pathologic hallmark is infiltration of mucosa or submucosa with abnormally increased cells (in the case of eosinophilic and lymphocytic gastritis, as well as Ménétrier’s disease) or reactive tissue (in the case of granulomas of sarcoidosis and tuberculosis).

Benign polypoid and mucosal mass lesions of the stomach are most commonly hyperplastic and seen in the setting of gastritis. These have a low potential for malignancy. Adenomatous polyps, which can be seen in the setting of polyposis syndromes mentioned previously, have a higher potential for malignancy and can be either tubular or villous. Finally, hamartomatous polyps, also seen in the setting of polyposis syndromes, are the least common of the subtypes.

Imaging

Ulcers

Gastric ulcer disease typically manifests as symptoms of epigastric or abdominal pain, which is worse with eating. These clinical symptoms are nonspecific and can be seen in a variety of abdominal pathologic processes, not just referable to the stomach. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasonography, and positron emission and computed tomography (PET/CT) are not generally useful in the diagnosis.

Radiography.

Evaluation of mucosal disease is best seen with double-contrast barium evaluation. Gastric ulcers appear as abnormal accumulations of contrast media that persist on different views. Within the stomach, these collections are most often round, as opposed to in the esophagus, where they can also appear as linear defects. In benign ulcers, the ulcer crater projects outside the gastric lumen. Additionally, mucosal folds are typically thin and extend to the margin of the ulcer (this is not seen with malignant ulcers or ulcerated masses). The pattern of mucosal ulcerations also can be useful. In the case of erosive gastritis caused by NSAID use, small ulcers are aligned along thickened folds ( Figure 20-1 ). Peptic ulcers tend to be solitary or few, but aphthous ulcers of Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease are often multiple.

Computed Tomography.

Studies have shown that multidetector CT with virtual gastroscopy is a useful way to distinguish benign from malignant gastric ulcers. Using criteria such as ulcer shape and margin (regular vs. irregular), gastric fold changes, and enhancement of the ulcer base, Lee and colleagues reported 80% to 90% sensitivity and 77% to 78% specificity for the differentiation of benign from malignant ulcers.

More commonly, CT is used generally to evaluate patients with abdominal pain. In these cases, gastric wall thickening or edema can be seen at the site of ulcers. Importantly, some of the complications of gastric ulcers can be readily detected by CT, including perforation ( Figure 20-2 ) and gastric outlet obstruction. Bleeding ulcers are less likely to be detected with CT.

Polyps and Masses

Gastric polyps and benign masses are generally clinically occult unless they cause bleeding or gastric outlet obstruction. These are typically incidentally detected with endoscopy or barium radiography. MRI, ultrasonography, nuclear medicine studies, and PET/CT are not generally useful in diagnosis.

Radiography.

The radiographic evaluation of benign mucosal polyps and masses again rests on the double-contrast barium upper gastrointestinal evaluation. Gastric polyps appear as filling defects on barium studies and can be pedunculated or tubular ( Figure 20-3 ) or villous. When numerous, the possibility of a polyposis syndrome is raised. Additionally, mucosal masses such as heterotopic pancreatic rests can have a characteristic appearance, typically with a centrally umbilicated mass in the pylorus.

Computed Tomography.

CT is not generally useful when imaging mucosal lesions unless there is a large mass or a complication such as gastric outlet obstruction.

Diffuse Mucosal Disease

Again, abdominal pain is the most common manifesting symptom in these cases and is nonspecific. If a patient has scarring or fibrosis, early satiety may be a symptom that would prompt evaluation of the stomach. Additionally, patients with Ménétrier’s disease present with hypoalbuminemia, which may prompt a search for an underlying cause.

Radiography.

Double-contrast barium radiography may be ordered in the patient with early satiety to evaluate for underlying neoplasm or mass. Barium studies may show gastric nondistensibility, or segmental scarring, such as in Crohn’s disease. The differential considerations for this appearance are wide, and close evaluation of the patient’s history may narrow the diagnostic possibilities.

Computed Tomography.

CT is generally not useful without a distended stomach. Wall thickening of the stomach can be simulated by underdistention.

Positron Emission Tomography With Computed Tomography.

PET/CT is not useful in the diagnosis of diffuse gastric mucosal disease. In patients who have PET/CT for other reasons, incidental detection of inflammatory processes such as gastritis may be seen with increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.

Imaging Algorithm.

In patients presenting with abdominal pain, the first-line imaging study is typically CT. If CT does not yield a diagnosis, the patient should proceed to double-contrast barium upper gastrointestinal study or endoscopy for further evaluation. The choice of these two procedures most often depends on the patient’s clinical status and pretest likelihood of disease.

- •

Hampton’s line (benign ulcer): Thin straight line at the base of the ulcer seen in profile indicating thin rim of undermined mucosa

- •

Ram’s horn sign (Crohn’s disease): Deformity, nondistensibility, narrowing, and poor peristalsis of the stomach antrum, leading to configuration similar to a ram’s horn

- •

Linear and serpiginous gastric ulcers: Aspirin/NSAID-induced erosive gastritis)

- •

Heterotopic pancreatic rests: A centrally umbilicated mass located in the pylorus

Differential Diagnosis

Abdominal and epigastric pain are classic symptoms of gastritis and ulcer disease. These are nonspecific symptoms and may prompt evaluation of the stomach only with the appropriate clinical history (e.g., NSAID use, history of Crohn’s disease or sarcoidosis).

As discussed previously, the differential diagnosis rests on categorizing mucosal diseases into their primary manifestations: ulcers, polyp and masses, and diffuse processes.

Malignant Mucosal Processes

Etiology

Malignant mucosal processes can have manifestations similar to those of benign disease, and it is helpful to categorize them according to their most common presentations. Overall, there is considerable overlap in the presentation of malignant gastric diseases because the major diseases—gastric adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, and metastatic disease—can manifest as any of the radiologic manifestations described here. Classifying these processes by their different mucosal manifestations—ulcer, polyp or mass, and diffuse mucosal processes—yields the following causes:

- •

Ulcers: Malignant gastric ulcer secondary to gastric adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, carcinoid, metastatic disease from melanoma, lung, adenocarcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma

- •

Polyps and masses: Gastric carcinoma, carcinoid

- •

Diffuse mucosal processes: Linitis plastica (gastric carcinoma, lymphoma, metastatic disease especially from breast cancer), Ménétrier’s disease with associated adenocarcinoma

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Both primary and metastatic malignancy can affect the stomach. Primary malignancies include adenocarcinoma (95%), lymphoma (4%), and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) (1%). Of metastatic malignancies, direct invasion from adjacent tumors of the pancreas or colon is more common than hematogenous metastases such as those from carcinoma of the breast and melanoma. Of these, malignancies that affect the gastric mucosa include adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, and hematogenous metastases.

Overall, gastric malignancy incidence has decreased over the past century. In the early 1900s, gastric cancer was the leading cause of death in men in the United States, whereas today it is not in the top 10. However, while the incidence has decreased in the West, gastric cancer is still relatively common in Asia and Eastern Europe, representing the second most common cancer. The highest prevalence occurs in Costa Rica, Japan, and the republics of the former Soviet Union, whereas the lowest prevalence is in the United States and parts of Africa and Southeast Asia. Overall, prognosis is poor, with 5-year survival at 22%, a statistic that has not changed significantly in the past 30 years.

Causes of gastric adenocarcinoma are unclear, but epidemiologic studies have pointed to diet (low in fruits and vegetables, high in nitrates and salt) as a factor. Additionally, H. pylori infection has been implicated in the increased risk for both adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. Genetic mutations, including those seen with Li-Fraumeni syndrome and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, increase the risk for gastric malignancy.

Unlike adenocarcinoma, the incidence of gastric lymphoma has been increasing. Similar to adenocarcinoma, infection with H. pylori is a risk factor and there can be significant regression of lymphomatous involvement with antibiotic treatment. Staging for gastric lymphoma, which is almost always the B-cell non-Hodgkin’s type, is the same as for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Pathology

Gastric adenocarcinoma, which accounts for 95% of gastric malignancies, is generally divided into two broad categories: type I (intestinal) and type II (diffuse). Type I adenocarcinoma is generally well differentiated, contains distinct glandular elements, is typically found in older male patients, and carries a better prognosis. Type II adenocarcinoma is poorly differentiated, is infiltrative, is found in younger and female patients, and carries a worse prognosis.

Gastric lymphoma, although less common, is the most common extranodal site for lymphomatous involvement. Almost all cases of gastric lymphoma are B-cell non-Hodgkin’s type. These can include both well-differentiated superficial mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and high-grade large cell lymphoma.

Imaging

Malignant Mucosal Disease

There is considerable overlap in the clinical presentation of benign and malignant gastric mucosal processes, including epigastric pain, weight loss, food avoidance, and anemia. Generally, because it is easier and less invasive to perform double-contrast barium radiography, this is often the initial test ordered.

Radiography.

Double-contrast barium radiography is often recommended as the first method of evaluation for patients presenting with a wide variety of epigastric or abdominal complaints. When mucosal abnormalities are present, they generally fall into one of three main categories: ulcers, polyps or masses, or diffuse mucosal disease. These three categories include numerous benign and malignant causes, and most often the patient must undergo endoscopic evaluation and biopsy for definitive diagnosis. There are, however, classically described findings in benign and malignant ulcers that may suggest a cause.

The goal of double-contrast barium radiography in the evaluation of mucosal ulcerations is to distinguish benign from malignant ulcers. Benign ulcers have been classically described as round, with thin mucosal folds radiating to the crater surface as well as projecting outside the gastric lumen. In contrast, malignant ulcers have nodular, irregular radiating folds that do not extend to the ulcer crater (ulcerated mass) and lie within the stomach wall. Using these criteria, those ulcers that clearly fall within the benign category do not need endoscopic confirmation according to the radiology literature. However, it is recommended in the internal medicine literature that all ulcers undergo endoscopic evaluation to confirm benignity.

In patients with mucosal polyps or masses seen on double-contrast barium radiography, the majority are benign hyperplastic or inflammatory polyps. However, because a percentage of these polyps are adenomatous and cannot be distinguished from hyperplastic polyps, endoscopic removal is recommended to exclude premalignant lesions. Villous polyps have a higher rate of malignancy (55%) and are removed endoscopically or surgically when found.

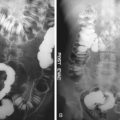

Thickened gastric folds and other diffuse mucosal presentations can have a variety of causes. In general, thickened, irregular, tortuous folds invoke an infiltrative cause, such as adenocarcinoma ( Figure 20-4 ), lymphoma, or metastatic disease. However, there is overlap with other conditions such as Ménétrier’s disease, which can be benign or associated with other malignancies ( Figure 20-5 ). Nondistensibility of the stomach is not helpful because it can be seen with scirrhous carcinoma and metastatic disease as well as benign causes such as Crohn’s disease and syphilis. When these findings are seen at double-contrast barium radiography, they should trigger further evaluation for the underlying cause.