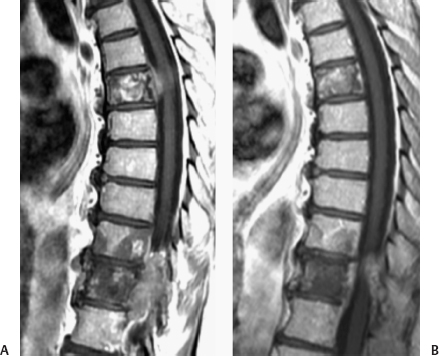

18 Optimal management of patients with spinal cord neoplasm requires collaboration between several disciplines: medical oncology, neurology, neurosurgery, radiation oncology, and radiology. The patients are a diverse group, but there are several guiding principles that aid in their assessment and management. Goals of care for the multidisciplinary team include early and accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, prevention and management of complications and comorbidities, functional improvement, and enhanced quality of life. This chapter will focus on some of the multidisciplinary aspects of caring for these patients. Most of our patients already have an established cancer diagnosis, and new patients may have an obvious primary neoplasm elsewhere, away from the spine. Occasionally, a patient presents with spinal metastases with an uncertain primary, or there may have been a time interval between a prior neoplasm and later metastases, making the tissue diagnosis uncertain. In such cases, a biopsy may be necessary. Prior to making this decision, it is useful to consider a complete workup to screen for malignancy elsewhere. For instance, an ambiguous solitary vertebral metastasis is more likely to be a metastatic focus if the workup reveals additional metastases elsewhere. Serum tumor markers can be used in this determination, such as prostate-specific antigen for prostate cancer, CA-15.3, CA-27, and CA-29 for breast cancer, and immunoglobulins for myeloma. There are three main ways that spinal tumors may present: incidental lesions in asymptomatic patients, those presenting with pain, and those presenting with neurologic symptoms. Most spine tumors are bone metastases to vertebral bodies. A variety of cancers metastasize to bone; the most frequently seen are breast, lung, and prostate cancers.1 We have observed that with newer and more effective systemic therapy, the natural history and metastatic pattern for certain cancers may be evolving; for instance, we have seen several cases of colorectal cancer with apparent hematogenous metastases to the spine, which previously was a rare occurrence. When surveillance studies indicate the incidental finding of an asymptomatic spinal metastasis, a decision needs to be made on whether further diagnostic study or lesion-specific treatment is necessary. Many asymptomatic lesions detected on a bone scan can have clinical follow-up. Solitary metastases may be considered for definitive treatment on an individualized basis. The common presenting pattern is pain. The typical picture is that of crescendo pain localized at the site of the radiographic abnormality over the spine, often with associated radicular pain or tenderness. For classic symptoms and a consistent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance, a decision may easily be made to treat. Unfortunately, the diagnosis is not always so straightforward. Back pain is a common diagnosis, even in patients without metastatic cancer. According to the results of a national survey, at least 2.5% of all medical visits in Ontario were because of malignant spinal cord compression pain.2 In a similar survey in Saskatchewan, the prevalence of back pain in adults was 28%.3 Patients may have pain from degenerative disease, muscular strain, or other conditions. Even in patients with definite metastases on imaging studies, their pain may not always be from the tumor. For example, vertebral compression fracture can cause pain generated by periosteal and soft tissue inflammation from the fracture. In such cases, MRI evaluation and multidisciplinary assessment will help determine the optimal management. The next common presenting pattern is with neurologic symptoms, including weakness, paresthesia, and incontinence.4 Making a diagnosis is usually straightforward in cases with rapid onset of classic symptoms. Typically, though, the symptoms are more subtle and can be confounded by concurrent neurologic conditions, such as peripheral sensory neuropathy from chemotherapy weakness from steroids or deconditioning.5 The most common chemotherapeutic agents that may cause neuropathy include the platinum compounds, taxanes, vinca alkaloids, thalidomide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil.6 Because clinical outcomes are improved with early treatment of symptomatic spinal cord compression, primary physicians need to remain vigilant. Multidisciplinary evaluation may be helpful in making the diagnosis of patients with overlapping neurologic symptoms. Multidisciplinary management can include several treatment modalities: surgery, fractionated radiotherapy, radiosurgery, systemic chemotherapy, steroids, physiotherapy, and attention to concurrent medical conditions. Many of these are addressed in other chapters. Most intramedullary spinal tumors are treated primarily with radiotherapy. In select cases we have also incorporated systemic chemotherapy. Patients with spinal cord gliomas can be treated with concurrent radiotherapy and Temodar (tomozolomide), in a fashion similar to brain gliomas.7 Patients with primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma with spine involvement may be treated primarily with chemotherapy, high-dose methotrexate, and/or rituximab.8 Patients may develop leptomeningeal metastases from a variety of tumors. About 5% of patients with advanced cancer may have clinical leptomeningeal metastases, but autopsy studies indicate that the prevalence may be considerably higher.9,10 Although cerebral or cranial nerve symptoms are typical presentations, many patients present with spinal symptoms. Presymptomatic patients may have the diagnosis suggested by MRI. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology is helpful in confirming the diagnosis, but it may not always be positive. If there is clinical suspicion, high-volume or repeat CSF cytology should be performed.11 If intrathecal chemotherapy is planned, a nuclear cisternogram should be considered to verify adequate CSF flow.12 If there is a block or bulky intraspinal or paraspinal tumor, then focal radiotherapy or radiosurgery may be considered to facilitate the distribution of the intrathecal medication. Chemotherapeutic agents for intrathecal administration include methotrexate, Ara C (cytarabine), and thiotepa. The spectrum of activity of these agents is limited, with predictable responses with leukemias and lymphomas, occasional responses with breast cancer, and rare responses with other solid tumors.13 Systemic chemotherapy agents can also be considered on an individualized basis, for example, Xeloda (capecitabine) in patients with breast cancer or highdose methotrexate for leptomeningeal lymphoma. The majority of cases discussed at the spine tumor board at Heny Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, have extra-axial systemic metastases to bone or paraspinal regions. In patients without spinal cord compression who have responsive tumors, such as lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and receptor-positive breast cancers, chemotherapy can be the primary treatment modality. A common dilemma is whether to treat with surgery or radiotherapy before systemic agents are used. For isolated metastases, nonresponsive tumors to chemotherapy such as renal cell carcinoma, or if there is encroachment into the canal, radiosurgery may be considered. There may be several vertebral levels that would need to be targeted. In such cases, multidisciplinary planning may be helpful to minimize the radiotherapy field and preserve marrow function to allow for later systemic therapy. Hormone therapy can achieve a rapid response in a subset of patients who present with pain and have advanced potentially hormone-responsive tumors, such as receptor-positive breast cancers and prostate cancer. We have seen dramatic responses within 1 or 2 days in prostate cancer patients treated with ketoconazole, or in breast cancer patients treated with an aromatase inhibitors. A patient with prostate cancer with spinal cord compression at T6 and T10-T11 causing lower extremity weakness is shown in Fig. 18.1. The T6 lesion was treated with ketoconazole alone, and the more severe T10-T11 lesion was treated with radiosurgery. A follow-up MRI scan showed significant tumor response to these treatments. However, special care must be taken because of the risk of tumor flair from luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) analogues or antiestrogens. Short-term follow-up with MRI and ancillary studies such as serum tumor markers should be performed in conjunction with clinical assessment. Patients responding to hormone therapy may have other modalities of treatment held, whereas those without early response may be considered for radiation. Bisphosphonates decrease osteoclastic activity, necessary for the lysis of bony cortex by skeletal metastases. They may also change the marrow microenvironment, with effects on the initiation and growth of metastases. Studies have documented reduction of pain and skeletal events in appropriately selected patients who are treated with these agents.14–16 The clinical benefits include a reduction in the rate of pathologic fractures, vertebral compression fractures in the spine tumor board population. Pain control may be enhanced with Zometa in patients with skeletal metastases.17 Patients with solitary or isolated metastases without apparent pathology in surrounding bone may not need systemic diphosphonates therapy. Most patients with diffuse disease, especially with a lytic component on plain film or CT, should be considered for treatment. Figure 18.1 Ketoconazole effect for prostate spinal cord compression. This patient presented with T6 and T10-T11 spinal cord compression with neurologic symptoms. The T6 compression was treated with ketoconazole alone, and the more severe T10-T11 compression was treated with 18 Gy radiosurgery. (A) Before treatment. (B) Two months after treatment. Bisphosphonates can also be used in patients with long-term steroid usage, those with ongoing treatment with aromatase inhibitors, and others at risk for osteoporosis. Bone density assessment can aid in determining which patients are candidates.18,19 Bisphosphonates can be used for prevention of compression fracture because the drugs can prevent bone loss.20

Multidisciplinary Combined Modality Approach for Cancer of the Spinal Cord

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Patient Presentation

Patient Presentation

Treatment

Treatment

Systemic Chemotherapy

Bisphosphonates

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree