Fig. 1 a–e.

Distal femur osteosarcoma in a 16-year-old girl. a Short TI inversion recovery (STIR) sequence is used to look for skip metastases. The Q body coils must be placed in order to get sufficient signal at the opposite side of the lesion. A surface coil placed on the tumor is then used to allow accurate local assessment of tumoral extension. b Coronal T1-weighted image. c Axial T2 fat-saturation image. d Coronal reconstruction of three-dimensional gadolinium T1 fat-saturation sequence. e Coronal ADC map (b0-b900) done at mid course of chemotherapy: signal measurement of the whole tumor would allow following the tumoral response

Surface coil centered on the tumor to look especially for a possible transphyseal extension. Coronal T1, axial T2, three-dimensional T1 fat-saturation gadolinium weighted sequences (Fig. 1) need to be done at the very least.

Diffusion weighted MR sequences may have an interesting role to play in early differentiation of poor and good responders to chemotherapy in osteosarcomas. Initial results that were obtained on a small series need to be confirmed before it can be used in current practice [2] (Fig. 1). 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET has also been used to assess the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in this indication. A strong correlation between a decrease in FDG uptake and tumor necrosis has been demonstrated. However, there is still no standardized uptake value threshold available that could definitely separate good responders from poor responders. The FDG-PET response is obtained too late in the treatment course to modify a potentially unsuccessful treatment [3–5].

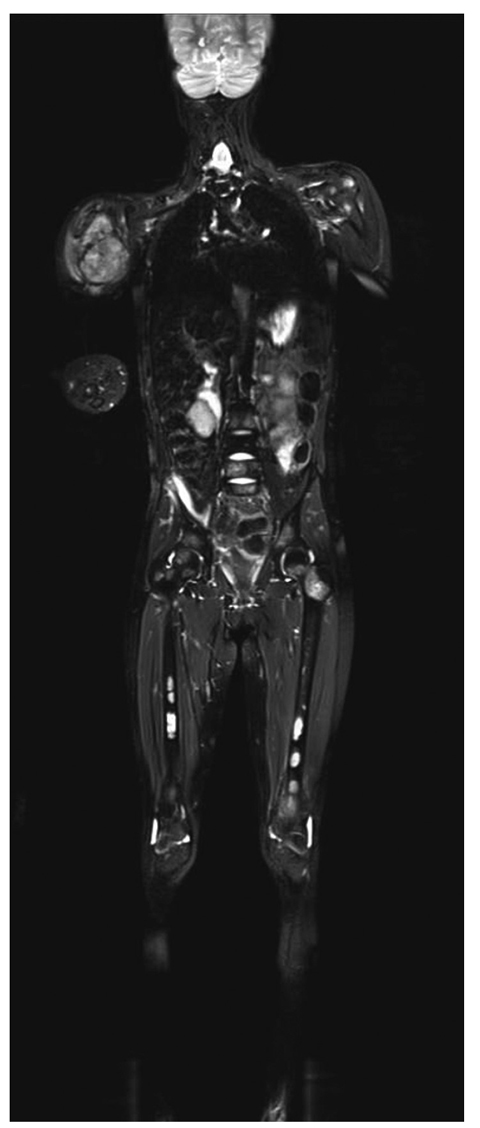

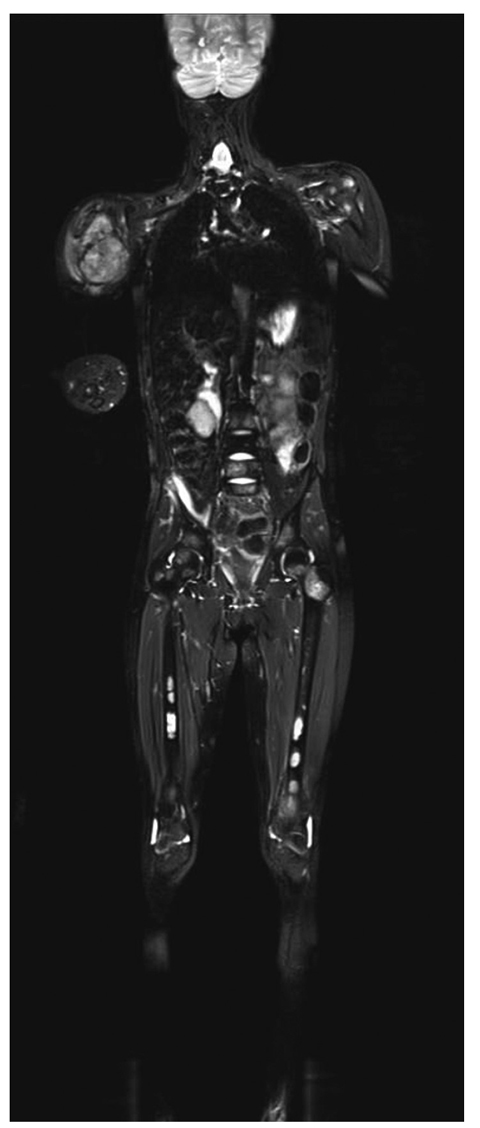

Whole body MR (WBMR) is gaining acceptance in pediatric radiology. Despite the length of acquisition (at least 20–0 min) and the need for sedation in the youngest patients, a high spatial resolution associated with an absence of radiation are obvious advantages of MR, compared with bone scan scintigraphy and PET-CT. WBMR has been demonstrated to be more accurate than Tc scintigraphy [6, 7]. However, comparative pediatric studies between WBMR and PET-CT are scarce in the literature [6]. They have mostly concentrated on tumoral diseases (Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, lymphoma, histiocytosis). Different MR sequences have been tested (T2 fat saturation, STIR, T1, diffusion) alone and in combination, and compared with PET-CT the results have been considered satisfactory [8, 9]. The addition of diffusion weighted sequences to STIR WBMR sequences has enhanced observation of the lesion and improved diagnostic accuracy for lymphomas [10]. Despite the potential application of WBMR in the investigation of metastases (Fig. 2), the major drawback is the length of exploration time (45 min).

Fig. 2

Whole body magnetic resonance imaging of a 13-year-old girl with Ewing sarcoma of the right humerus. Fusion images of short TI inversion recovery (STIR) and diffusion weighted sequences reveal numerous bone metastases (for color reproduction see p 307)

Soft Tissue Tumors

Regarding this topic, the eternal question that is particularly relevant is: ‘how can we obviate to miss a malignant soft tissue tumor without to ask any time for a biopsy. Most of these lesions are benign (pseudotumors, vascular tumor and vascular malformations, fibrohistocytic tumors). The age of the patient, site of the lesion, clinical history and especially chronicity of the lesion are cornerstones of diagnosis. Some predisposing diseases should also be investigated (neurofibromatosis, Li Fraumeni syndrome, etc.) [11].

Malignant tumors are rare, accounting for around 1% of all soft tissue tumors in pediatrics. Rhabdomyosarcoma accounts for 50% of all soft tissue sarcomas. The most frequently occurring non-rhabdomyosarcoma malignant tumors are tumors of the peripheral primitive neuroectodermal/ Ewing (pPNET/Ew) sarcoma family (19%), malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (6.5%), infantile fibrosarcomas (6%) and synovial sarcomas (5%) [12].

The following clinical criteria indicate strong suspicion of malignancy: size greater than 5 cm, increase in size, pain and deep location of the lesion [11].

The first radiological approach is ultrasound (US) Doppler. X-rays and MR imaging are second-line investigation techniques. CT should not be carried out if there is suspicion of a soft tissue tumor, except if myositis ossificans is suspected.

Rhabdomyosarcoma (Fig. 3) can occur at any age, and the principal differential diagnosis is the intramuscular venous malformation (VM). Therefore it is important that the radiologist can clearly separate these two entities, and in order to do this US must be used to look for some specific features. The presence of fluid-fluid level in the lesion is not sufficient to provide a diagnosis of VM. On the other hand, the presence of some poor arterial flow (<15 cm/s) does not exclude a diagnosis of VM. It is then essential to look for a round-shaped phlebolith, with or without posterior shadowing. Rhabdomyosarcoma is principally composed of tissues of different echogenicity, usually with a rich arterial flow. One must take into account that even with the high sensitivity of Doppler, absence of Doppler flow does not mean that the lesion is not vascularized. However, this finding indicates a possible benign nature of the lesion. Contrast US is of interest in this setting, and particularly to separate rhabdomyosarcoma from VM [13]. However, this technique has not received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in pediatric practice. The actual strategy used to differentiate rhabdomyosarcoma from VM is explained in the abstract of the workshop “Vascular malformations of the pediatric musculoskeletal system”, in the Kangaroo course.

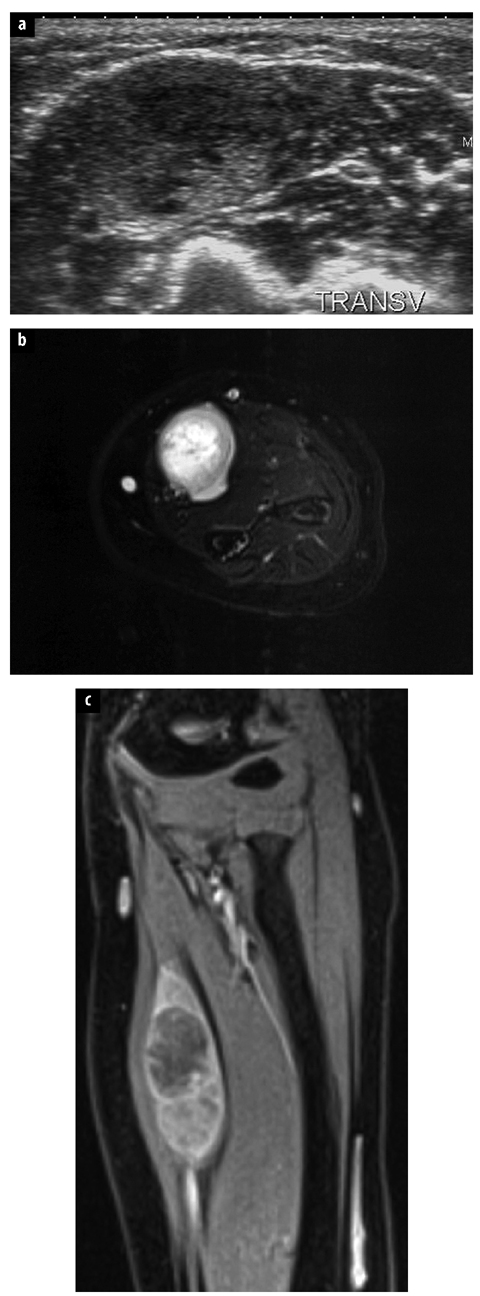

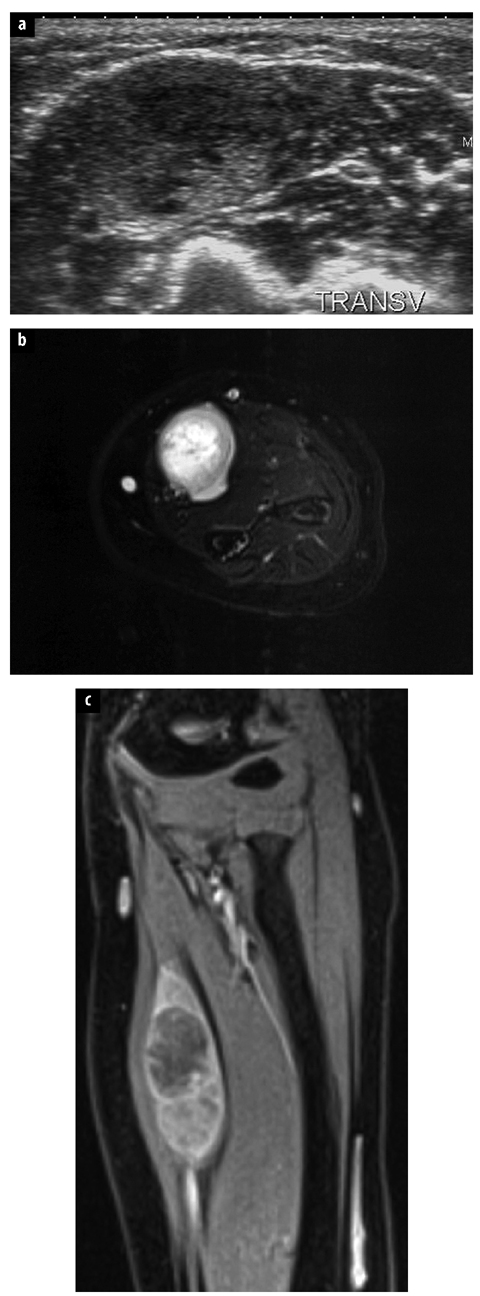

Fig. 3 a–c.

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma of the left forearm in a 2- year-old girl. a On ultrasound, the intramuscular mass can be misdiagnosed for a recent thrombosed venous malformation. b Axial T2 fat-saturation weighted image reveals a frank mixed hypersignal without fresh hemorrhage. c T1 gadolinium coronal fat-saturation weighted image shows an enhancing intramuscular lesion with excentric necrotic area

When the lesion has not been definitely recognized clinically, or by US and X-ray imaging, then MR exploration is mandatory [14]. Once again, this examination must be done prior to biopsy or surgery in order to accurately delineate the limits of the tumor, and sometimes to allow recognition of the lesion. We recommend to always use at least a Spin Echo (SE) T2 sequence without fat saturation to allow correct assessment of the pure fluid into the lesion. With a T2 fat-saturation sequence, necrotic malignant lesions and myxoid lesions may have a pseudocystic appearance. Gadolinium injection is always indicated, except when a VM or a lymphatic malformation has been definitely recognized on US Doppler. Criteria in favour of malignancy are: size (more than 5 cm), absence of low signal intensity on T2, signal heterogeneity on T1, peripheral and centripetal contrast enhancement, contiguous invasion of bone and/or neurovascular structures However, none of these MR criteria are 100% specific [11].

MR diffusion has not proved to be capable to either separate benign from malignant processes, or evaluate post-therapeutic changes accurately [15].

All soft tissue masses that are of uncertain origin must be subjected to a multidisciplinary approach in order to decide the type of biopsy (fine-needle aspiration, core biopsy, surgical open biopsy) necessary, and the destination of the samples (histopathology, immunohistochemistry and/or cytogenetic laboratories).

Pediatric Inflammatory Disease (Infectious)

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis [16] is defined as an infection of the bone marrow; the most common causal organism is Staphylococcus aureus. Less frequently, Streptococcus spp., Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are cultured from blood or aspirates [17]. The incidence of Haemophilus influenzae osteomyelitis has decreased dramatically since the introduction of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccination. The manifestation of osteomyelitis in children is age-dependent. In infants, diaphysial vessels penetrate the growth plate to reach the epiphysis, facilitating epiphysial and joint infections in this age group.

In older children, the growth plate constitutes a barrier for the diaphyseal vessels. Vessels at the metaphysis terminate in slow-flow venous sinusoidal lakes, predisposing the metaphysis as the initiation point for acute hematogenous osteomyelitis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

A one and a half year old girl who refuses to bear weight on her left foot, and shows fever. The lucent lesion represents metaphyseal osteomyelitis. The epiphysis was not affected

The increased pressure within the medullary cavity causes the infection to spread via the Haversian and Volkmann’s canals into the subperiostal space. Because the periosteum is less firmly attached to the cortex in infants and children than in adults, elevation will be more pronounced in childhood osteomyelitis. In contrast, sequestration is rare in neonatal osteomyelitis [17].

Conventional radiography is usually the initial modality used to demonstrate deep soft tissue swelling in early disease. However, bone destruction and periosteal reaction become obvious but only 7–10 days after the onset of disease. Conventional radiography is a screening method that can often suggest a diagnosis, exclude other pathology, and be correlated with other imaging findings.

Ultrasonography (US) can detect cortical defects and abscesses in the course of the disease (Fig. 5). Detection of subperiosteal abscesses is especially important because US-guided aspiration or surgical drainage has to be considered in these patients, whereas those with osteomyelitis without abscesses can be treated with antibiotics only. CT demonstrates osseous abnormalities earlier in the course of the disease than conventional radiographs; however, this is at the expense of a higher dose of radiation. It is superior to MR imaging for visualizing bone destruction, gas in the bone and bone sequestration.

Fig. 5 a–d.

A 5-year-old boy with intermittent swelling of the left ankle after a minor trauma 1 year ago. a Radiograph at the time of trauma shows no abnormalities. b Radiograph 1 year later demonstrates soft tissue swelling, cortical thickening and a cortical defect. Growth line in tibia probably represents the initial event. c, d Ultrasonography shows a sequestrum floating in a soft tissue abscess that communicates with the bone marrow through a small cortical defect (arrow). Chronic osteomyelitis. Cultures were positive for Staphylococcus aureus

MR is, as with CT, not a screening method, but an invaluable method of demonstrating the intra- and extraosseous extent of osteomyelitis. Predictors of early osteomyelitis are ill-defined low T1 and high T2 signal intensity, poorly defined soft tissue planes, lack of cortical thickening and poor interface between normal and abnormal marrow. In chronic osteomyelitis, there is good differentiation between diseased marrow and soft tissue abnormalities [18].

(Spondylo)discitis

Spondylitis, spondylodiscitis and discitis in children are perhaps different manifestations of the same disease: a low-grade infection affecting the vertebral body and intervertebral disc [21]. Many organisms cause spondylo — discitis; even low-grade viral infection has been postulated in patients with no positive cultures (50%) [22]. The clinical symptoms may be subtle, varying from limping, the inability to stand or sit upright, to frank back pain. The first radiological sign is intervertebral disc space narrowing with indistinct endplates on either side, and this eventually leads to destruction of the endplates. The best imaging technique is MR imaging, which demonstrates signal intensity abnormalities in the intervertebral disc and adjacent vertebral bodies.

Septic Arthritis

The hip joint is the most frequent location of septic arthritis in childhood; the knee, shoulder and elbow are also common sites [17]. Early diagnosis is mandatory to prevent cartilage destruction, joint deformity, growth disturbance and eventually premature arthrosis. Most commonly, it is caused by hematogeneous seeding or, less frequently, by extension into the joint space from osteomyelitis. Etiologic organisms are S. aureus (most common), group A streptococci and Streptococcus pneumoniae. In neonates, group B streptococci and E. coli are important causes, whereas Neisseria gonorrhoeae can be a cause in adolescents [17]. The incidence of H. influenzae has declined since large vaccination programs were introduced. The presenting sympoms are fever, nonweight bearing, erythrocyte sedimentation rate >40, and peripheral white blood cell count of >12,000. If all these symptoms are present, the likelihood of septic arthritis is 99% [23]. Unfortunately, many children do not show such an obvious clinical picture and imaging techniques are important tools to give additional information about the suspected joint.

Conventional radiographs can be normal or they can demonstrate joint space widening with adjacent soft tissue swelling. However, sensitivity and specificity for septic arthritis is low.

US is very sensitive for the detection of joint effusion, especially in the pediatric population, and small amounts, up to 1 mL, can be detected. However, the specificity of the diagnosis is poor. The absence of joint effusion virtually excludes septic arthritis [24]. Neither the size nor the echogenicity of the effusion can distinguish an infectious from a noninfectious effusion [25, 26].

CT is less sensitive for the detection of joint effusion, but may identify areas of adjacent osteomyelitis. MR is very sensitive for the detection of synovial disease [27]. Initially, MR imaging reveals distention of the joint capsule by nonspecific T2 high intensity fluid. In later stages, the joint effusion tends to have a more intermediate signal intensity and seems to be heterogeneous. Moreover, MR can demonstrate cartilage destruction and adjacent cellulitis [28]. Combined with gadolinium injection and fat suppression techniques, sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 77% can be accomplished with MR [29].

Soft Tissue Infections

Cellulitis, Soft Tissue Abscesses and Necrotizing Fasciitis

Cellulitis, soft tissue abscesses and necrotizing fasciitis are infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, with a predilection for the extremities in children [30]. S. aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes account for the majority of the infections. Patients present with soft tissue swelling, erythema and fever.

Conventional radiographs often show nonspecific soft tissue swelling. The US appearance resembles edema of the subcutaneous fat, showing swelling, increased echogenicity of the subcutaneous fat with decreased acoustic transmission, blurring of tissue planes, progressing to hypoechoic strands between hyperechoic fatty lobules. This appearance is nonspecific and cannot be distinguished from noninfectious causes of soft tissue edema [31]. Increased vascularity at color or power Doppler US can suggest an infectious cause [32].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree