, David C. ShonkaJr.2, Max Wintermark3 and Prashant Raghavan4

(1)

Division of Neuroradiology, Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

(2)

Division of Head and Neck Surgical Oncology, Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

(3)

Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

(4)

Division of Neuroradiology, Department of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Abstract

The nasopharynx is located at the crossroads between the skull base superiorly, the nasal cavity anteriorly, and the oropharynx inferiorly. Disease processes can spread to and from the nasopharynx through well-defined anatomic pathways. The focus of this chapter will be on nasopharyngeal carcinoma, with a brief overview of a few other lesions.

3.1 Introduction

The nasopharynx is located at the crossroads between the skull base superiorly, the nasal cavity anteriorly, and the oropharynx inferiorly. Disease processes can spread to and from the nasopharynx through well-defined anatomic pathways. The focus of this chapter will be on nasopharyngeal carcinoma, with a brief overview of a few other lesions.

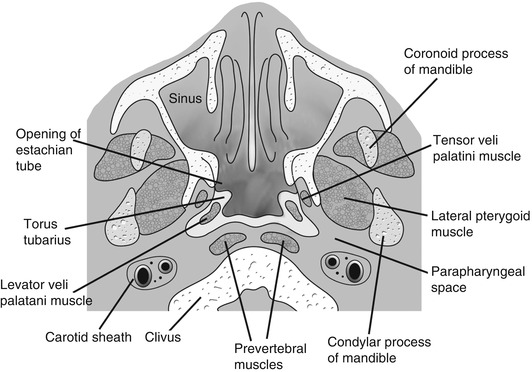

3.2 Anatomy and Physiology

The nasopharynx is located posterosuperior to the hard palate and contains adenoidal lymphoid tissue and an abundance of minor salivary glands. It is bound by the floor of the sphenoid sinus and clivus superiorly, by the nasal choanae anteriorly, by the posterosuperior surface of the soft palate anteroinferiorly, by the prevertebral musculature and clivus posteriorly, and by the parapharyngeal spaces laterally. It is continuous with the oropharynx inferiorly. The lateral wall of the nasopharynx includes the fossa of Rosenmüller, located lateral and posterior to the torus tubarius (the cartilaginous opening of Eustachian tube); the fossa is the most common site of primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) (Figs. 3.1 and 3.2). Also along the lateral wall are the tensor and levator veli palatini muscles, separated by a small fat pad, the effacement of which is an early radiographic sign of NPC (Figs. 3.2 and 3.3).

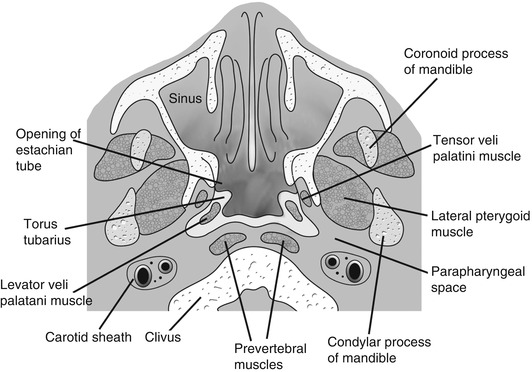

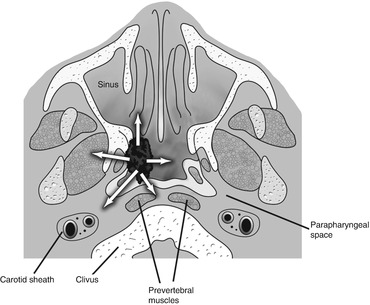

Fig. 3.1

Axial graphic of the nasopharynx showing the important landmarks. Just behind the elevated torus tubarius lies a fat-filled mucosal recess known as fossa of Rosenmüller. Evaluation of this recess is critical for identifying early nasopharyngeal carcinomas

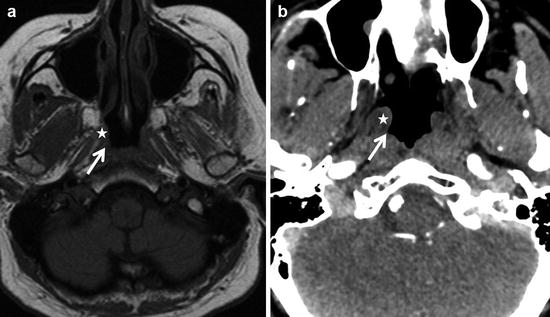

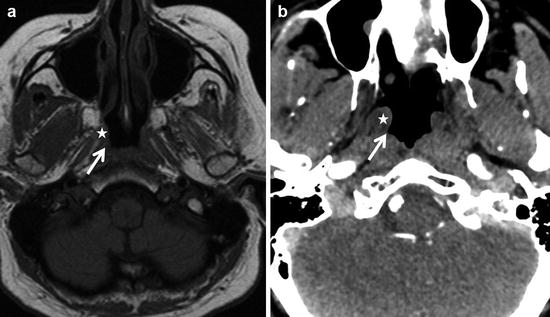

Fig. 3.2

Normal axial CT and MR of the nasopharynx. (a) (CT) and (b) (T1 MR) showing the relevant anatomy, consisting of torus tubarius (white star) and the fossa of Rosenmüller (white arrow) behind it. Effacement of the fat in this region with asymmetrical fullness is seen in early nasopharyngeal carcinomas

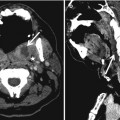

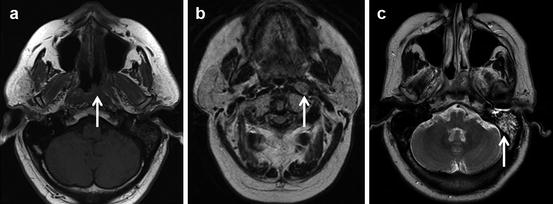

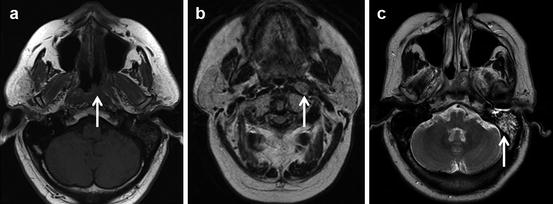

Fig. 3.3

Early nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Subtle effacement with fullness along the left lateral nasopharyngeal wall (arrow in a), along with pathological left retropharyngeal node (arrow in b), and left mastoid effusion (arrow in c), due to Eustachian tube dysfunction in this patient with biopsy-proven nasopharyngeal carcinoma

NPCs have a high propensity to invade local structures; the extent of local invasion significantly impacts staging and prognosis. An important avenue for expansion is via the sinus of Morgagni, a potential gap in the pharyngobasilar fascia between the superior edge of the superior constrictor muscle and the skull base. This sinus allows NPC to enter the parapharyngeal and other adjacent deep extra mucosal spaces.

The lateral retropharyngeal nodes of Rouvier represent the first echelon nodes in nasopharyngeal lymphatic drainage. They are typically ventral to the prevertebral musculature and medial to the carotid sheath (Fig. 3.3).

3.3 Pathology

The nasopharynx can be involved by congenital lesions such as notochord remnant (e.g., Thornwaldt’s cyst) basal encephaloceles and epidermoids, dermoids, hamartomas, and neurenteric cysts. Lesions arising from the sella and the clivus can also extend inferiorly to involve the nasopharynx. Benign acquired lesions of the nasopharynx include squamous papillomas, antrochoanal polyps, and hemangiomas. Infectious and inflammatory changes of the nasopharynx occur secondary to involvement of the adenoids. Extension of infection can also occur from the sinuses or from osteomyelitis of the central skull base. Many of these aggressive infections are either fungal or granulomatous (e.g., tuberculosis) and are usually associated with immunocompromise; thus, they should be considered in patients with HIV, undergoing active immune suppression, (e.g., posttransplant, autoimmune disorders), being treated with chemotherapy, or with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.

NPC represents the predominant malignancy in the nasopharynx, comprising almost 80 % of the known malignant lesions with lymphomas being the next most common. Rarer malignancies include nasopharyngeal melanomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, and minor salivary gland malignancies. The predominant benign tumor of the nasopharynx is the juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA). These arise from the sphenopalatine foramen and frequently involve the nasopharynx (Fig. 3.4); they are discussed in the sinonasal chapter.

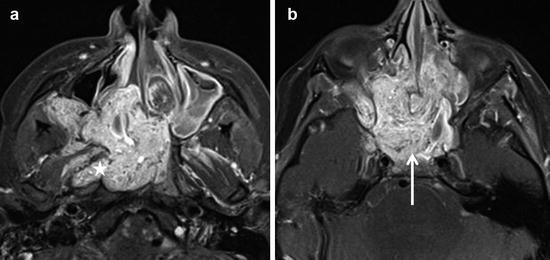

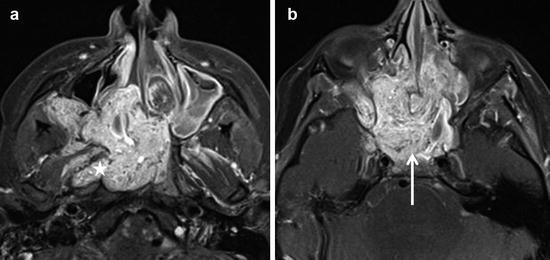

Fig. 3.4

Axial post-contrast MR images (a, b) demonstrate a large heterogeneously enhancing mass involving the right pterygopalatine fossa, sinonasal cavity, nasopharynx, and central skull base (arrow in b). Note the extension of the tumor laterally from the nasopharynx into the right fossa of Rosenmüller, torus tubarius, and Eustachian tube orifice (white star in a). This was a biopsy-proven juvenile angiofibroma

3.4 Imaging Evaluation

Nasopharyngeal lesions are usually evaluated using a combination of contrast-enhanced CT and MRI scans. Axial and coronal views are the mainstays. On CT scans, thin (0.5–1 mm) sections are usually obtained and reformatted in multiple planes to provide the requisite soft tissue and bony detail. MRI scans are usually obtained with 3–4 mm sections and a field of view of approximately 10–15 cm. A combination of fat-suppressed pre- and post-contrast T1- and T2-weighted images, in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes is obtained for adequate evaluation. MRI is superior for evaluating locoregional extent of tumors, including skull base and intracranial extent. CT provides better definition of local bony destruction. FDG-PET can be helpful for detecting distant metastases and in the evaluation of therapeutic response posttreatment. Catheter angiography is sometime used in the evaluation of nasopharyngeal lesions such as JNAs.

3.5 Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

NPC is unique when compared to squamous cell carcinomas elsewhere in the head and neck. It is more common in people from Southeast Asia, especially those from southern China. In the USA, NPC is more commonly seen in Americans of Chinese ancestry. The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified NPC into three broad histological patterns: Type 1, keratinizing squamous carcinoma; Type 2, nonkeratinizing squamous carcinoma (with or without lymphoid stroma); and Type 3, undifferentiated carcinoma (with or without lymphoid stroma). Types 2 and 3 comprise the bulk of NPC. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma has a bimodal presentation: a subset of younger (15–30 years old) patients with Type 3 cancers (in patients from China and of Chinese descent) and a second subset of older patients (>40 years old) who typically have Type 1 and Type 2 cancers. A small group of aggressive, poorly differentiated NPC (pediatric NPC) occurs in adolescents, with a propensity for advanced locoregional and distant spread.

The TNM classification for nasopharyngeal carcinoma is summarized in Box 3.1. Involvement of parapharyngeal space (PPS) (T2 lesion) results in a worse prognosis as compared to involvement of the nasal cavity or oropharynx (Fig. 3.5). Other landmarks to be noted include osseous structures of the skull base and paranasal sinuses for T3 lesions (Fig. 3.6); intracranial extension and/or involvement of cranial nerves and orbits or with extension to the infratemporal fossa/masticator space, which are T4 lesions (Figs. 3.6 and 3.7).

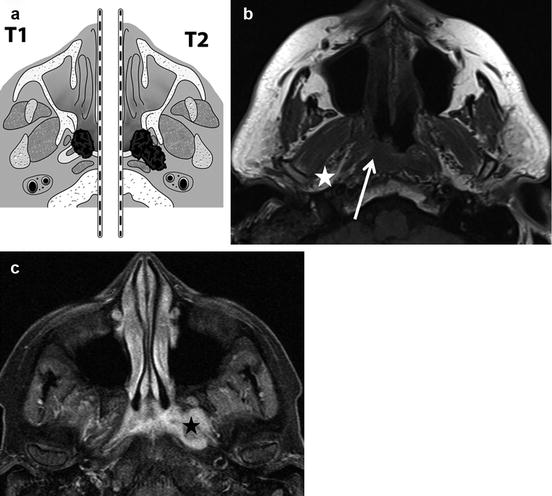

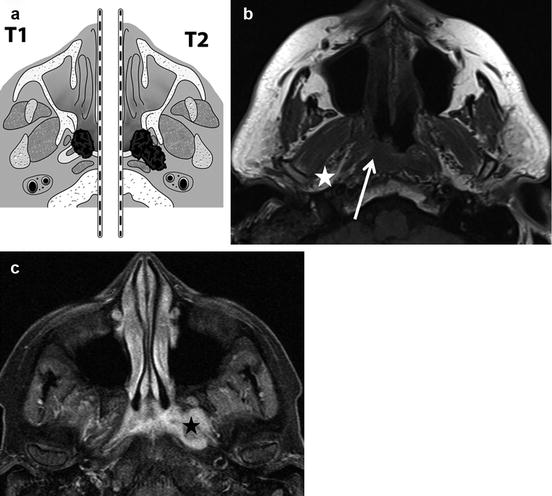

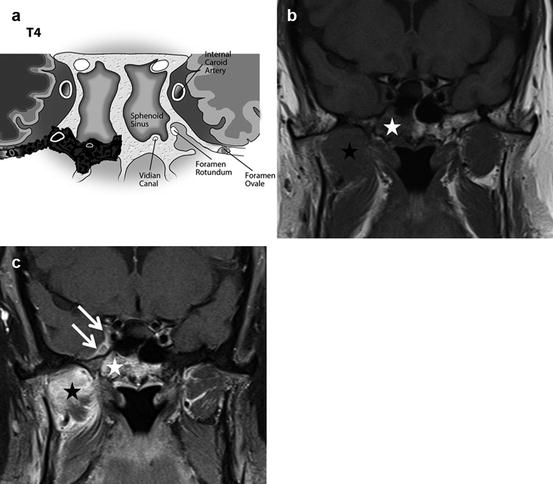

Fig. 3.5

Axial graphic (a) shows T1 and T2 lesions. T2 lesions extend into the adjacent parapharyngeal space. Axial T1 non-contrast MR elegantly demonstrates the subtle loss of T1 fat signal in the right lateral nasopharyngeal recess (white arrow), with preserved normal right parapharyngeal fat of a T1 tumor (white star in b). Axial T2 fat saturated sequences show a T2 tumor on the left (black star in c) with involvement of the left parapharyngeal recess

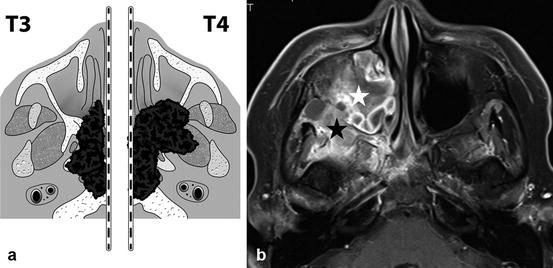

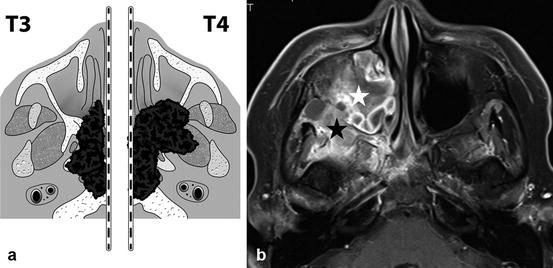

Fig. 3.6

Axial graphic (a) showing T3 (extension into the bony structures and paranasal sinuses) and T4 tumors (extension into masticator space). Axial T1 post-contrast sequences (b) demonstrates a T4 lesion on the right which involves both the right maxillary sinus (white star) and the right infratemporal masticator space and central skull base (black star)

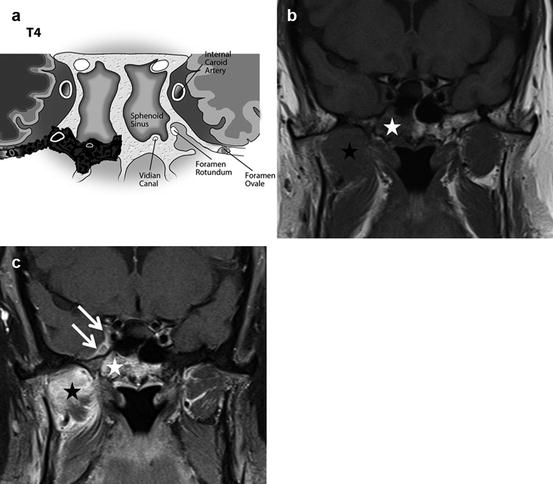

Fig. 3.7

Coronal graphic (a) demonstrating T4 lesion extending to the right central skull base and the foramen rotundum and foramen ovale with intracranial extension. Axial T1 pre- (b) and post-contrast sequences (c) show a T4 lesion in the right masticator space (black star) involving the central skull base/clivus (white star) with intracranial extension into the right cavernous sinus through the right foramen rotundum along the V2 division of the right trigeminal nerve (white arrows)

The most common imaging appearance of NPC is a mass centered at the lateral nasopharyngeal recess (fossa of Rosenmüller) with deeper extension and associated cervical nodal disease (Fig. 3.8). Frequently, the tumor is identified extending beyond the nasopharynx into adjacent spaces. NPCs spread along these well-defined routes (Fig. 3.9), and care should be taken to evaluate these areas on imaging (Box 3.2):

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

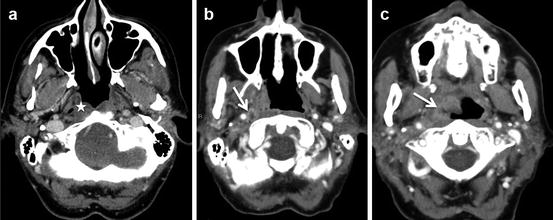

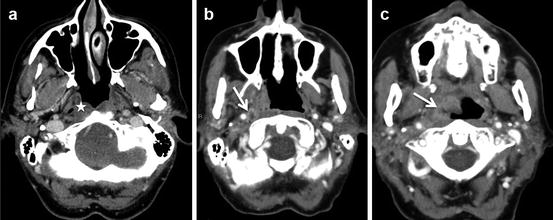

Fig. 3.8

Axial contrast-enhanced CT images (a, b and c) demonstrate the common imaging appearance of NPC as a mass centered at the lateral nasopharyngeal recess (fossa of Rosenmüller) (star in a) with pathological retropharyngeal adenopathy (arrow in b). Note the inferior extension along the right nasopharyngeal wall (arrow in c)

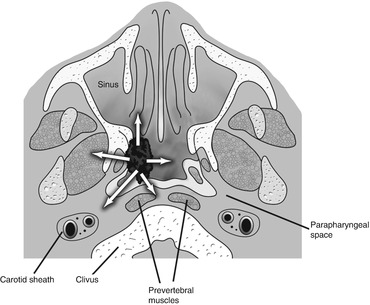

Fig. 3.9

An axial graphic showing the various pathways of spread of a NPC. These include anterior extension into the nasal cavity; lateral extension into the parapharyngeal, masticator, and carotid spaces; and posterior extension into the prevertebral space. NPC is also notorious for superior extension into the clivus and skull base with intracranial extension

1.

Lateral spread is the most common via the sinus of Morgagni into the parapharyngeal space. This appears as effacement of the parapharyngeal fat triangle. From there, the tumor might extend into the masticator space and involve the pterygoid muscles which are associated with trismus, or into the carotid sheath (Fig. 3.10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree