Necrotizing (“Malignant”) Otitis Externa

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography can make the presumptive diagnosis of necrotizing otitis externa when the disease is beyond its early stage and produces at least some bone erosion.

- Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is useful in treatment surveillance, based on the evaluation of soft tissue changes. Bony changes during healing cannot be used to help monitor therapy.

- Radionuclide studies also can help to assess the response to antimicrobial therapy but are of limited specific diagnostic value.

INTRODUCTION

Etiology

Necrotizing (“malignant”) otitis externa (NOE) is a spreading necrotizing infection of the external auditory canal (EAC) soft tissue that can produce an osteomyelitis of the entire skull base. It is most commonly caused by pseudomonas but is also less commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus mirabilis. Aspergillus may also be a causative agent.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

NOE is a sporadic condition that occurs principally in elderly diabetic patients usually caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. It may occur in other immune-compromised patients, including those with HIV infections, hematological malignancies, and pharmacologic immune suppression.

Clinical Presentation

Patients typically will present with otalgia and swelling with granulation tissue present at the junction of the bony and cartilage portions of the EAC accompanied by drainage from an obvious external otitis. More advanced cases will have a deeper form of otalgia with headaches and perhaps fever and signs of septicemia. In more advanced cases, there will be a cranial neuropathy that can involve cranial nerves V through XII, most commonly VII or X.

Pathophysiology

Anatomy

The anatomy of interest is that of the entire temporal bone and posterior skull base, described in detail in Chapter 104. In particular, the detailed anatomy of the EAC and petrotympanic fissure must be understood to evaluate the disease properly in its early stages (Figs. 104.21–104.23). It is also useful to understand the relationship of the surrounding anatomy, including the temporomandibular joint and masticator and parapharyngeal spaces (Chapter 142).

Pathology and Patterns of Disease

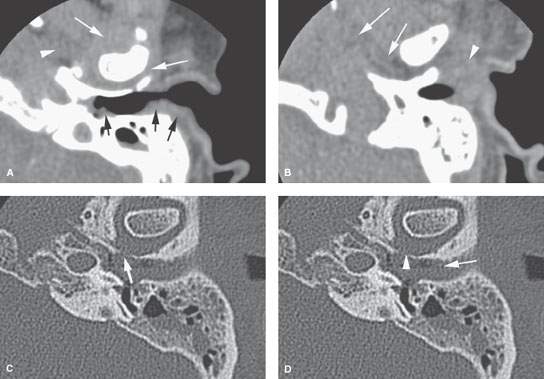

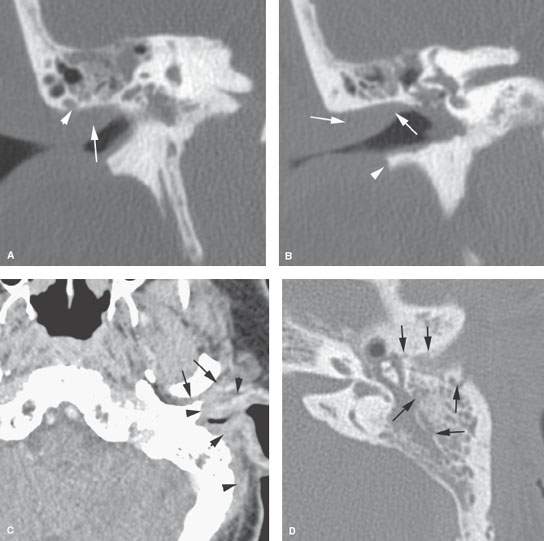

This is a spreading, necrotizing infection that starts in the soft tissues and affects bone from the outside to the inside. It is best thought of as a periosteal spreading pattern with regard to how it follows bone. The earliest finding is nonspecific soft tissue swelling within and around the EAC (Fig. 114.1). In the next stage of the disease, bone will be demineralized at the petrotympanic fissure, correlating with the clinical tendency for granulation tissue to accumulate at the bony cartilaginous junction and then infiltrate medially along the tympanic bone to its juncture with the petrous portion (Fig. 114.1). Erosion along the walls of the EAC and into the mastoid air cells is a relatively less common initial spread pattern (Fig. 114.2).

FIGURE 114.1. Computed tomography study of a patient with relatively early necrotizing otitis externa. A: Soft tissue changes are an early sign of disease and frequently involve the planes around the temporomandibular joint (white arrows) and the parapharyngeal space (arrowhead) as well as the pinna and external auditory canal (EAC) (black arrows). B: A more inferior section showing the typical soft tissue swelling of the pinna and along the cartilage portion of the EAC (white arrowhead) and more advanced deeper soft tissue swelling in the parapharyngeal space (arrows). C: Bone windows showing early erosion of bone in the EAC (arrows) and soft tissue swelling within the canal (arrow). D: The EAC is filled with soft tissue swelling. The most common site of bone erosion in the external canal is more proximal than that seen in (D) and closer to the region of the petrotympanic fissure (arrowhead).

Later-stage disease will spread along the periosteal surfaces of the mastoid and petrous portions of the temporal bone, usually following the eustachian tube, to the petrous apex (Fig. 114.3) and posterior skull base, frequently reaching the clivus (Figs. 114.4 and 114.5) and at times crossing to the other side (Figs. 114.4 and 114.5). Frank subperiosteal or other abscess formation is possible but only rarely presents and certainly is not a prominent part of the gross morphology of the disease. When present, it may suggest an etiology other than pseudomonas or a superimposed second bacterial infection with a more pyogenic organism (Fig. 114.5C,D). The surrounding cellulitis at the skull base may be very extensive.

Intracranial spread is a very late stage of the disease and not commonly encountered, as antibiotics effective against pseudomonas have been introduced.

Pathologically Altered Function

Typically, there are no specific deficits created early in the pathogenesis of the infection. More extensive or aggressive lesions can cause cranial neuropathies. Inner ear dysfunction secondary to labyrinthitis and intracranial and vascular complications are uncommon compared to other aggressive bacterial infections of the temporal bone.

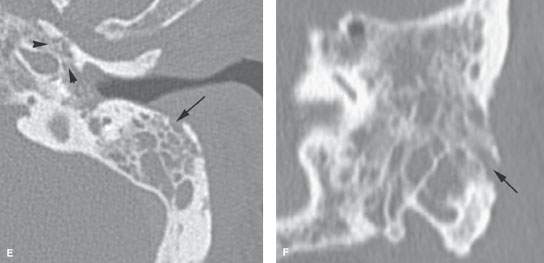

FIGURE 114.2. Two patients with mastoid involvement due to necrotizing otitis externa (NOE). A, B: Computed tomography study of Patient 1 with relatively early NOE. In (A), the coronal image shows erosion along the superior canal wall involving a mastoid air cell (arrowhead). There is extensive swelling within the canal. Bone erosion primarily along the mastoid is somewhat unusual. In (B), extensive swelling is present in the external auditory canal (EAC); this is a nonspecific finding. There is fairly extensive bone erosion along the inferior canal wall (arrowhead)—a relatively common pattern seen at the junction of the bone and cartilage portions of the canal. C–F: Patient 2. In (C), there is extensive soft tissue swelling of the external ear and along the mastoid (arrowheads) as well as along the posterior aspect of the temporomandibular joint (arrows). In (D), there is extensive bone erosion along the anterior wall of the EAC in addition to multiple areas of mastoid bone erosion. In (E), bone erosion extends along the petrotympanic fissure in a fairly typical pattern (arrowheads), but it also involves the mastoid cortex in a less typical pattern. In (F), the coronal reformation shows the direct involvement of the mastoid laterally.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree