Neoplasms

Pilocytic Astrocytoma

This benign, World Health Organization (WHO) grade I, tumor occurs in the cerebellum, optic pathway (optic nerve, chiasm), thalamus/hypothalamus, and brainstem (pons). It is the most common posterior fossa tumor of childhood (although close in incidence to medulloblastoma). Pilocytic astrocytomas are slow growing and typically large at diagnosis. In the cerebellum a lesion in the hemisphere (laterally located) is more common than in the vermis (medially located). The classic presentation is that of a cystic posterior fossa lesion, with an enhancing mural nodule, extrinsic to and causing mass effect upon the fourth ventricle ( Fig. 1.106 ). The cystic component will be hyperintense to CSF on FLAIR, due to protein content. A pilocytic cerebellar astrocytoma can thus present with obstructive hydrocephalus. Solid pilocytic astrocytomas also occur in the cerebellum, but like their cystic counterpart, are typically well circumscribed. Lesions involving the optic chiasm and optic nerve (optic glioma) are not uncommon in neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1); however, many such lesions are found in patients who do not have NF1. Enhancement of an optic tract lesion is variable, and can be absent. In the pons, a relatively large lesion is the most common presentation (with the lesion limited to the pons). Contiguous involvement of other portions of the brainstem (and thus a rather extensive lesion extending superiorly and/or inferiorly) occurs, but is rare.

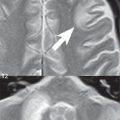

Tectal (quadrigeminal plate) gliomas are included here for discussion due to their indolent nature. This is a sub-type of brainstem glioma, presenting in childhood and young adults. Features include periaqueductal location, lack of contrast enhancement, and long-term stability. Tectal gliomas present as a small bulbous mass lesion, hyperintense on T2-weighted scans, and often narrow the cerebral aqueduct causing obstructive hydrocephalus (and thus clinical presentation). These are considered to be very low-grade lesions, with histology usually not available, and conservative management recommended. The main differential diagnostic consideration is benign aqueductal stenosis. The latter however can be distinguished by the presence of only a thin rim of periaqueductal T2 high signal intensity, without an associated mass.

Low-grade Astrocytoma

This WHO grade II tumor is infiltrative in nature, histologically well differentiated, and demonstrates slow growth with time. On imaging, its presentation is that of a focal mass lesion with its epicenter in white matter. Low-grade astrocytomas on MR are well-defined, homogeneous, non-enhancing mass lesions, with little mass effect and minimal vasogenic edema. They are hypointense on T1- and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The appearance of this lesion on MR, as a seemingly well-defined mass, is somewhat misleading relative to its infiltrative nature ( Fig. 1.107 ). The most common location is that of the frontal or temporal lobe. A rather characteristic location is in the insula extending medially to lie adjacent to the MCA trifurcation. Low-grade astrocytomas are poorly visualized on CT (they are often isodense with brain). Calcifications are noted in 25%. Clinical presentation is generally in the third to fifth decades of life, and they are a common primary tumor of adults. About half of pontine gliomas ( Fig. 1.108 ) are low-grade astrocytomas, as distinguished from pilocytic (WHO grade I) astrocytomas.

A general comment about astrocytomas is in order. On biopsy, different portions of a lesion commonly display different histology (and a different grade). Lesions are also not static histologically with time, with eventual progression in grade seen (from low-grade to anaplastic to a glioblastoma multiforme).

Anaplastic Astrocytoma

As with almost all features, this tumor is intermediate between a low-grade astrocytoma and a glioblastoma multiforme in histology (this is a WHO grade III tumor), imaging appearance, and prognosis. On MR, in distinction to a low-grade astrocytoma, an anaplastic astrocytoma is less well defined, mildly heterogeneous, often exhibiting some contrast enhancement, and displays mild to moderate mass effect and accompanying vasogenic edema ( Fig. 1.109 ). Intravenous contrast administration on MR is important for identification of recurrent or residual tumor (both with anaplastic astrocytomas and glioblastomas), with enhancement however correlating more closely only with the higher grade portions of the lesion. Recurrent tumor usually enhances, even if preoperatively it did not. One caveat is important about abnormal enhancement following surgery. A follow-up exam should always be obtained within 24 hours after resection, at which time any abnormal enhancement (along or adjacent to the resection margin) will be due to residual tumor, with postoperative changes causing abnormal enhancement only in subsequent days. Abnormal contrast enhancement does not differentiate between radiation necrosis (which usually occurs more than 1 year following treatment) and recurrent tumor. Perfusion (CBV) studies, either by CT or MR, however permit this differentiation. Diffusion also plays a role both in assessing tumor grade and in the identification following treatment of recurrent tumor. Histologic tumor grade (for glial tumors) correlates inversely with the minimum ADC. ADC maps provide information analogous to FDG-PET, allowing an approximation of tumor grade. And, for differentiation from chemoradiation injury, a reduction in ADC generally correlates with recurrent tumor. Radiation and chemotherapy reduce tumor cellularity, and thus usually lead to an increase in ADC.

Glioblastoma Multiforme

When considering astrocytomas of all grades, a glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common tumor ( Fig. 1.110 ). It is also the most common of all primary intracranial tumors. The hallmark on histology of this lesion is necrosis. When compared to lower grade astrocytomas, patients with a GBM are older, have a shorter duration of preoperative symptoms, and have a shorter survival. This highly malignant, WHO grade IV, widely infiltrative lesion grows along white matter tracts, with extension histologically of tumor beyond any border marked on imaging by high signal intensity on T2-weighted images or abnormal contrast enhancement. The typical location is in the cerebral hemisphere, with a frontal lobe location slightly more common than other lobes. Multiple lobe involvement and spread via the corpus callosum to the opposite hemisphere are not uncommon ( Fig. 1.111 ). The prognosis is poor, with survival of 1 to 2 years. Treatment includes surgical resection (with the greater the extent of tumor removed, the better prognosis), followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy (temozolomide and bevacizumab).

The appearance of a glioblastoma multiforme on MR (and on CT, although lesions are less well depicted with this modality) is distinctive, being a large lesion with a thick irregular enhancing ring, gross central necrosis, substantial mass effect, and extensive vasogenic edema in the adjacent white matter. The white matter tracts of the corpus callosum are very compact, thus high signal intensity extending along the corpus callosum on T2-weighted scans represents tumor extension, not edema. In a small percent of patients, on additional focus of tumor may be visualized distant from the primary lesion with apparent intervening normal brain.

Gliomatosis Cerebri

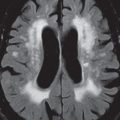

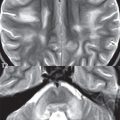

By definition, this diffusely infiltrating glial tumor involves three or more lobes of the brain. Although it infiltrates, and enlarges the involved brain, the underlying brain architecture is largely preserved. Gliomatosis cerebri has abnormal high signal intensity on T2-weighted scans, ( Fig. 1.112 ) where the involvement is best depicted, and typically displays no abnormal contrast enhancement.

Oligodendroglioma

This is a well differentiated, slowly growing cortical and subcortical, typically WHO grade II tumor, most commonly located in the frontal lobe, presenting in young to middle-aged adults. Oligodendrogliomas arise in white matter, and are usually peripherally located. Calcification is common, about half of all lesions mildly enhance, and there is rarely substantial associated edema. Due to their slow growth and location, they can cause calvarial erosion/remodeling ( Fig. 1.113 ). Fifty percent of oligodendrogliomas are mixed lesions (oligoastrocytoma). Although often seemingly well-defined on imaging, oligodendrogliomas are infiltrating lesions histologically. Treatment is by surgical excision and radiation.

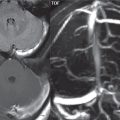

Higher grade tumors do occur, specifically anaplastic (WHO grade III) oligodendrogliomas and mixed lesions ( Fig. 1.114 ). Lesion perfusion is commonly assessed on imaging, typically by MR. As a general rule, higher grade gliomas demonstrate higher CBV, although oligodendrogliomas can have foci of high CBV, irrespective of grade. The most common benign tumor of the brain, a meningioma, also can have high CBV. With MR, there are two different techniques to acquire perfusion information, echoplanar dynamic imaging during bolus intravenous contrast administration and arterial spin labeling (ASL)—the latter not requiring contrast administration. The spatial resolution of ASL is however lower, and only CBF measurements can be obtained (not mean transit time) ( Fig. 1.115 ).

Ganglioglioma

The temporal lobe is the most frequent location for this slow growing, well demarcated, lower grade tumor (80% are grade I). The frontal and parietal lobes are the next most common locations. Gangliogliomas can be solid or cystic with a mural nodule, the latter being the most common presentation ( Fig. 1.116 ). Additional imaging characteristics include little or no associated edema, calcifications (in about half of cases), and contrast enhancement (in about half). Treatment of this tumor, which occurs in older children and young adults, is by surgical resection, which carries a relatively good prognosis.

Hemangioblastoma

This is the most common primary cerebellar tumor in an adult, although it should be kept in mind that the most common posterior fossa neoplasm in an adult is a metastasis. This highly vascular tumor is most commonly located in the cerebellar hemisphere. Most cases are sporadic, with von Hippel-Lindau disease patients predisposed to development of hemangioblastomas, both in the cerebellum and spine. The classic presentation is that of a well-defined cystic mass with a peripheral enhancing mural nodule ( Fig. 1.117 ). The signal intensity of the cyst on MR will be readily differentiable from CSF on FLAIR. One-third of lesions are solid. Enlarged associated blood vessels are often noted.

Primary CNS Lymphoma

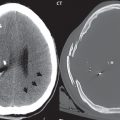

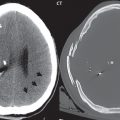

Lymphoma is the one diagnosis often not included in the differential (for lesions that subsequently prove to be lymphoma), so an important entity to keep in mind. Lymphoma carries a poor prognosis. The classic imaging description follows, although many lesions do not have this appearance. The presentation is that of an enhancing mass lesion, within the basal ganglia or periventricular white matter ( Fig. 1.118 ), often involving the corpus callosum. The common misconception is that this tumor is always or most often located in central white matter. In one clinical series, this was true in only 30% of cases. Lymphoma tends to be hyperdense on CT, and exhibit restricted diffusion on MR due to its high cellularity, the latter an important differential diagnostic point. On T2-weighted scans lymphoma may appear slightly hypointense to brain, another somewhat characteristic feature. The lesion is usually large at presentation (> 2 cm), in immunocompetent patients. There is usually prominent peritumoral edema. In immunocompromised patients (with this patient population having an increased incidence of lymphoma) there may be central necrosis with peripheral enhancement.

Medulloblastoma

The alternative term for medulloblastoma is a posterior fossa primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET). This is the second most frequent brain tumor of childhood after pilocytic astrocytoma, and the most common malignant lesion (it is WHO grade IV). Medulloblastomas are tumors of childhood and young adults, although predominantly occurring in the first decade of life. Histologically, this embryonal tumor is a heterogeneous disease with distinct subtypes, felt to originate from neuronal stem cells. These tumors most commonly arise from the roof of the fourth ventricle (the superior medullary velum). The tumor may either encroach upon or fill the fourth ventricle, with normal brain displaced ( Fig. 1.119 ).

In older patients medulloblastomas may arise in the cerebellar hemispheres. This highly cellular tumor is hyperdense on CT, demonstrates restricted diffusion, may appear relatively isointense with brain on T1- and T2-weighted sequences, and most commonly demonstrates intense enhancement. Abnormal contrast enhancement is however not always seen with medulloblastomas, and the enhancement can be heterogeneous. Small cystic or necrotic areas are noted in about half of all cases. Clinical presentation is often with increased intracranial pressure due to rapid tumor growth and obstructive hydrocephalus. Dissemination at the time of presentation in the CSF is common. Medulloblastomas are treated by surgical resection followed by chemotherapy and craniospinal radiation. The primary differential diagnoses include pilocytic astrocytoma, ependymoma, choroid plexus papilloma, and atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree