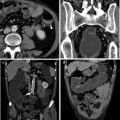

Fig. 10.1

59-year-old male patient with endoscopically detected sigmoid colon carcinoma. Water enema multidetector CT (a, b) depicts a 5-cm long lesion with circumferential mural thickening and regular external borders, consistent with a T2 stage tumour. In another 52-year-old male patient with an endoscopically impassable stage sigmoid colon cancer, an enhancing mural thickening with pericolonic fat infiltration (T3 stage) and luminal stenosis is detected (c, d). In both cases water enema CT colonography allows comprehensive exploration of the upstream colon, nodal and visceral staging

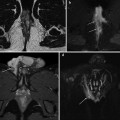

Alternatively, tumours of the rectum are exquisitely visualized by means of external phased-array coils Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as solid rectal wall thickening with abnormal signal intensity and enhancement (Fig. 10.2). MRI comprehensively demonstrates the tumour height and size, its extramural growth, the presence of perirectal lymph nodes and the distance of the tumour from the key anatomic landmark represented by the mesorectal fascia [19, 20].

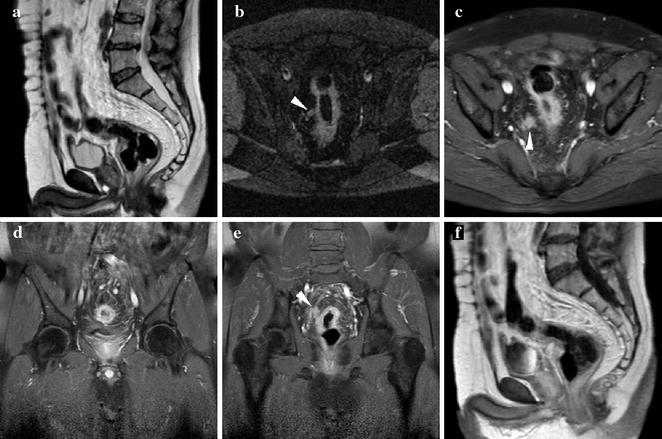

Fig. 10.2

60-year-old male patient with ulcerative colitis and endoscopic detection of rectosigmoid carcinoma. MRI including sagittal T2- (a), axial STIR (b) and post-contrast fat-suppressed (c–e) and unsuppressed (f) T1-weighted images effectively depicts 6-cm long circumferential full-thickness mural thickening, with strong contrast enhancement, irregular external margins, and at least one nodal metastasis (arrowheads) in the perivisceral fat

10.2 Low Rectal and Anal Carcinoma

An increased risk of anus and lower rectum carcinomas has been reported in patients with long-standing, severe perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease (CD). In patients with CD, anal cancer occurs 20 years earlier than the general population, and reaches a 14 % proportion among all colorectal tumours, which is ten times higher than the usual figure. However exceptionally, anal tumours may occasionally develop also in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC)-related chronic perianal inflammation (Fig. 10.3). The hypothesized pathogenesis involves an easier access of Human Papillomavirus to the anal epithelial layers due to fistulas, and chronic mucosal regeneration ultimately leading to neoplastic changes [21, 22].

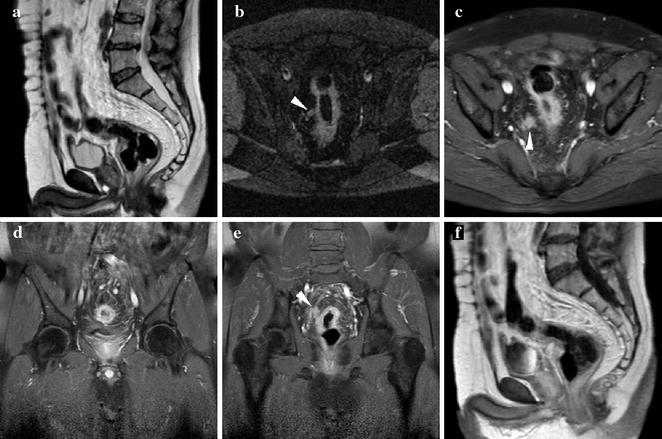

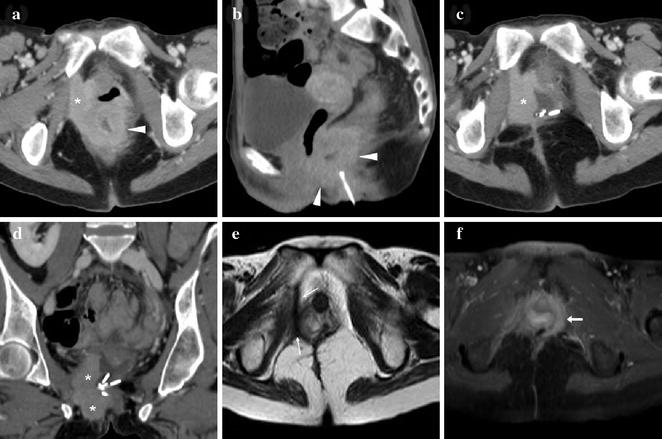

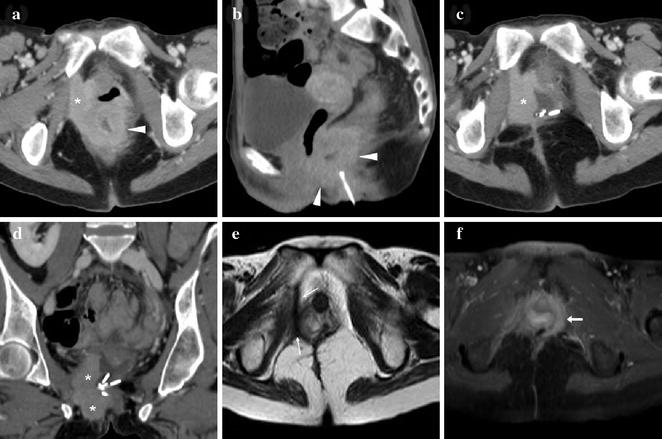

Fig. 10.3

39-year-old female with history of ulcerative colitis and perianal inflammation. Initial multiplanar MDCT (a, b) identified enhancing anal thickening (arrowheads) with right-sided vaginal infiltration and solid tissue (*) extending to reach the internal obturator muscle. After biopsy confirmation of SCAC and surgical debulking with colostomy, repeat MDCT (c, d) detected enlarging neoplastic residue (*). Shortly after chemoradiotherapy, MRI (e) detected the formation of a thick hypointense fibrotic band in the site of the regressed tumour (thin arrows). MRI follow-up (f) identified appearance of a contralateral enhancing tissue band interpreted as suspicious for local recurrence (arrow). After negative clinical reassessment and PET findings, this post-treatment finding remained stable on further MRI studies (not shown) (reprinted from Open Access Ref. no. 24)

The diagnosis of anal carcinoma in patients with IBD is usually unsuspected or delayed because of the pre-existent, unspecific complaints and because clinical assessment is hampered by complex inflammation with stricture and local pain. As a result, IBD-associated anal cancers are often advanced at presentation, may require extensive surgery plus chemo- and radiotherapy, and are associated with a severe prognosis [21–23].

Therefore, patients with long-standing IBD-related perianal inflammatory disease should undergo clinical and imaging surveillance, particularly when new or changed symptoms develop. Radiologists should be aware of the increased risk for anorectal cancer in middle-aged IBD patients, and clearly report any solid tissue as suspicious for neoplasm and suggest biopsy [21–24].

Currently, MRI represents the imaging modality of choice for primary regional staging of anal cancer. Solid neoplastic tissue shows low- to intermediate T1 signal intensity, T2- and STIR hypersignal superior to the internal reference standard represented by uninvolved anal sphincters and gluteal muscles, and positive enhancement after intravenous gadolinium contrast. Although with limited sensitivity compared to MRI, on CT images anal cancer may be detected as solid, enhancing nodules or masses within the anus, with progressive heterogeneity with increasing size [24–26].

As recommended by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), MRI is the primary imaging modality to accurately stage anal cancer taking into account the maximum tumour diameter, possible invasion of adjacent organs and nodal involvement. After radio-chemotherapy, imaging follow-up with MRI complements clinical evaluation in the assessment of therapeutic response, and of possible recurrences [24–26].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree