Fig. 1 a, b

a Coronal reformatted maximal intensity projection (MIP) image of a three-dimensional (3D) SPACE sequence demonstrates normal appearance of the bilateral sciatic nerves (short arrows) and superior gluteal nerves and associated vessels (long arrows) exiting the greater sciatic foramen. b Coronal reformatted MIP image of a 3D SPACE sequence demonstrates the exiting right L3 and L4 lumbar nerve roots (short arrows) as well as the lumbar contribution of the femoral nerve (long arrow). Note that the vessels are also projected in the reformatted MIP images

Table 1

Lumbosacral plexus muscular innervations by nerve root

T12 | L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Obturator internus | * | * | |||||||||

Obturator externus | * | * | * | ||||||||

Pectineus | * | * | * | ||||||||

Psoas major | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||

Iliacus | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||

Iliopsoas | * | * | * | ||||||||

Gluteus minimus | * | * | |||||||||

Gluteus medius | * | * | |||||||||

Gluteus maximus | * | * | |||||||||

Piriformis | * | * | |||||||||

Adductor brevis | * | * | * | ||||||||

Adductor longus | * | * | |||||||||

Adductor magnus | * | * | |||||||||

Levator ani | * | * |

Sciatic Nerve

The sciatic nerve is the largest peripheral nerve in the body and is reliably demonstrated on computed tomography (CT) and MRI [5]. It is formed from the L4-S3 nerve roots and most often descends anterior to the piriformis muscle. After exiting the pelvis through the infrapiriformis greater sciatic foramen, it descends in the thigh between the adductor magnus and the gluteus maximus muscles (Fig. 2). The sciatic nerve is composed of the medial tibial and the lateral common peroneal divisions, which provide motor innervation to the posterior thigh muscles, and all motor function below the knee (anterior, lateral, posterior and deep muscular compartments). It gives all sensory innervation to the lower limb with the exception of medial sensory innervation of the thigh and leg, which is provided by the obturator and femoral nerves.

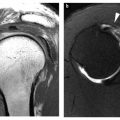

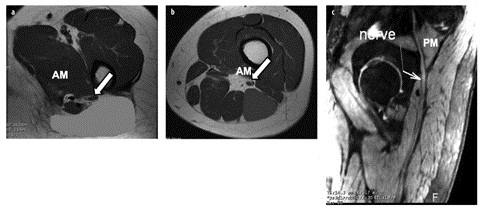

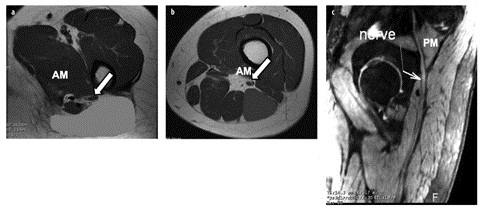

Fig. 2 a–c

Normal sciatic nerve. Axial T1 magnetic resonance images, just below the lesser trochanter (a) and at the proximal thigh (b), demonstrate the sciatic nerve (arrow) descending in the thigh between the adductor magnus (AM), gluteus maximus (green) and biceps femoris long head (blue) muscles. c Sagittal maximal intensity projection three-dimensional PSIF (preexcitation refocused steady-state sequence) image depicts the sciatic nerve (arrow) exiting the pelvis at the level of the greater sciatic notch beneath the piriformis muscle (PM) (for color reproduction see p 306)

Superior and Inferior Gluteal Nerves

The superior gluteal nerve is formed from the posterior roots of L4, L5 and S1. It exits the pelvis, through the suprapiriformis greater sciatic notch, and then passes between the gluteus minimus and gluteus medius muscles before giving off superior and inferior branches (Fig. 3). The superior branch terminates in the gluteus minimus muscle and the inferior branch terminates in the tensor fascia lata. The superior gluteal nerve acts to abduct the thigh at the hip by providing motor innervation to the gluteus minimus, gluteus medius and tensor fascia lata muscles.

Fig. 3

Coronal T2 image demonstrates bilateral superior gluteal nerves (arrows) curving under the roof of the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscles

The inferior gluteal nerve formed from the posterior roots of L5, S1 and S2 provides motor innervations to the gluteus maximus, which with the aid of the hamstrings, acts to extend the thigh. It exits the pelvis through the infrapiriformis sciatic notch and lies medial to the sciatic nerve before its terminal branch provides motor innervation to the gluteus maximus muscle. The superior and inferior gluteal nerves have no sensory contribution.

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve arises from L2 and L3, descends lateral to the psoas muscle, crosses the iliacus muscle deep to its fascia, and passes either through or underneath the lateral aspect of the inguinal ligament to the lateral thigh where it divides into anterior and posterior branches (Fig. 4). It innervates the skin on the lateral aspect of the thigh, and as its name implies is purely sensory.

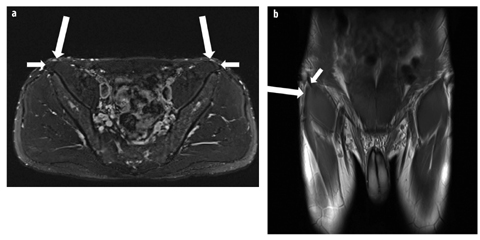

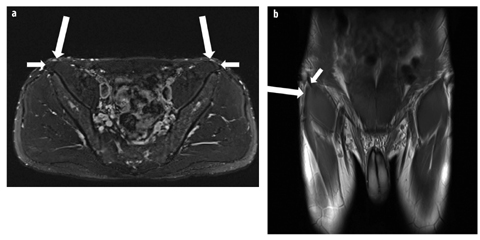

Fig. 4 a, b

Normal lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. a Axial T2 fat-saturated image demonstrates the bilateral lateral femoral cutaneous nerves (long arrows) adjacent to the anterior superior iliac spine origin of the sartorius (short arrows). b Coronal proton density image demonstrates the right lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (long arrow) at the level of the anterior superior iliac spine. Note the close relationship with the origin of the sartorius muscle (short arrow)

Femoral Nerve

The femoral nerve is formed by the L2, L3 and L4 nerve roots and descends between the iliacus and psoas muscles before exiting the pelvis under the inguinal ligament, in a canal between the iliopsoas muscle and the iliopectineal fascia (Fig. 5). It gives off a motor branch to the iliacus and the psoas muscles before dividing into anterior and posterior divisions and forming the saphenous nerve. The femoral nerve controls hip flexion and knee extension by providing motor innervation to the iliacus, psoas, pectineus, sartorius and quadriceps femoris muscles. Sensory innervation is of the medial thigh, anteromedial knee, medial leg and foot.

Fig. 5

Axial T2 image depicts the relationship of the femoral nerve (arrow), artery (*) and vein in the groin, going from lateral to medial. The femoral nerve can be difficult to visualize in the pelvis

Obturator Nerve

The obturator nerve is formed by the L2–L4 ventral rami. It descends into the pelvis, running along the ilio – pectineal line, exiting the pelvis via the obturator canal, at the superior aspect of obturator foramen. Within the pelvis, it assumes a near vertical orientation anterior to the psoas muscle and is well demonstrated on coronal imaging. It divides into an anterior branch, which passes anterior to adductor brevis and supplies the hip, and a posterior branch, which passes within the obturator externus muscle, and between adductor brevis and magnus muscles. The anterior branch gives motor innervation to the hip, gracilis, adductor brevis and longus muscles and occasionally the pectineus muscle, while the posterior branch supplies the obturator externus and a portion of the adductor magnus muscles. Sensory innervation is to the medial thigh and knee.

Pudendal Nerve

The pudendal nerve is formed by the ventral rami of S2, and all of the rami of S3 and S4. It passes between the piriformis and the coccygeus muscles and leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen. After crossing the ischial spine, it re-enters the perineum through the lesser sciatic foramen and travels in Alcock’s canal along the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossa (Fig. 6). The major branches are the inferior rectal nerve, the perineal nerve and the dorsal nerve of the penis or clitoris. Motor innervation is of the bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus muscles and the external urethral and rectal sphincters, while sensory innervation is of the perineum, scrotum and anus.

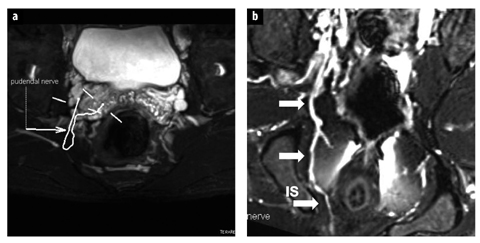

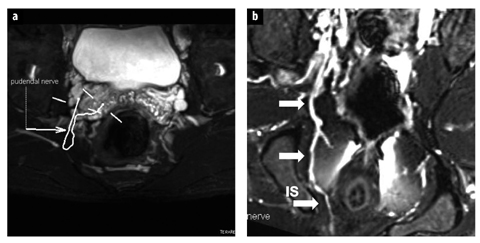

Fig. 6 a, b.

Normal pudendal nerve. a Axial three-dimensional (3D) SPACE STIR image demonstrates mapping of the pudendal nerve on consecutive overlapped images. b Maximal intensity projection 3D SPACE STIR demonstrates the normal course of the right pudendal nerve and vessels (arrows) posterior and medial to the ischial spine (IS)

Iliohypogastric Nerve

The iliohypogastric nerve is formed mainly from the anterior division of L1 with a small contribution from T12, and runs anteriorly and inferiorly along the lateral border of the psoas major and quadratus lumborum muscles. It pierces the transversus abdominus muscle and runs within the lateral abdominal wall, above the iliac crest, before dividing into its lateral and anterior cutaneous branches. Its terminal branch runs parallel to the inguinal ligament and exits the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. The nerve provides motor innervation to the abdominal wall musculature, and sensory innervation to the skin above the inguinal

Ilioinguinal Nerve

The ilioinguinal nerve is formed from the anterior division of L1, sometimes with a small contribution from Axial T2 image depicts the relationship of the femoral nerve T12. It runs a similar course to the iliohypogastric nerve, running inferiorly along the quadratus lumborum before piercing the lateral abdominal wall and running medially to the inguinal ligament. It contributes to motor innervations of the abdominal wall musculature, and gives sensory branches to the pubic symphysis, femoral triangle, labia majora or root of the penis and scrotum.

Genitofemoral Nerve

The genitofemoral nerve is formed by the anterior divisions of L1 and L2 nerve roots and pierces the psoas major muscle at the L3/L4 level before dividing into two branches which run along the anterior margin of the psoas muscle. The medial, genitalis or external spermatic, branch in males enters the inguinal canal and runs along with the spermatic cord to supply the cremaster muscle, spermatic cord, scrotum and adjacent thigh, and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. In females, it runs with the round ligament of the uterus and gives sensory innervations of the labia majora and adjacent thigh. The lateral, or femoral, branch runs lateral to the femoral artery and posterior to the inguinal ligament into the proximal thigh, where it pierces the sartorius muscle and supplies the proximal lateral aspect of the femoral triangle. It is a purely sensory nerve.

Imaging Findings

MRI plays a crucial role in evaluating patients with neurogenic pain and in characterizing potential etiologies. With recent technical advances in MRI, and particularly the advent of MR neurography, direct and indirect signs of neuropathy can be demonstrated even in the absence of a detectable compressive etiology. Diagnostic criteria for neural pathology include increased size of the nerve (larger than the adjacent artery), increased intraneural T2 signal and abnormal fascicular morphology, including focal enlargement or loss of definition of the internal fascicles. Nerves might have an abnormal course, with infiltration of the perineural fat when involved in scarring, and abnormal shape when focally enlarged or involved by tumor. Normal nerves should not enhance, except in those locations where the blood-nerve barrier is absent (dorsal root ganglion). Enhancement is most commonly seen in the setting of tumor or inflammation [3].

Indirect signs of neuropathy, particularly muscle denervation patterns, are also a very useful secondary sign of pelvic neuropathy. Increased T2 signal in the setting of muscular denervation does not represent true edema, and is best termed ‘edema-like signal’ or denervation signal alteration. This can progress to muscular fatty replacement, which is best detected on T1 weighted imaging, and eventually to muscle atrophy. Edema-like signal without fatty replacement is potentially reversible, if the underlying neuropathy resolves. There are multiple differential considerations for increased intramuscular T2 signal. Denervation edema-like signal is characterized by diffuse homogeneous involvement of the entire muscle, sharp margins, lack of associated fascial and perifascial fluid or inflammation, and conformation to a particular nerve distribution. Occasional variant innervation configurations and plexopathy can, however, confuse the pattern of muscle denervation changes.

Pathology: General Concepts

A wide variety of pathology can result in abnormal imaging findings of the pelvic nerves and musculature, ranging from infectious and inflammatory lesions, systemic diseases such as polymyositis to benign and malignant space occupying processes. Pathology, which tends to result in painful neuropathic symptomatology, is usually due to local causes, and can be divided into three major categories: (1) space occupying lesions, (2) post-traumatic lesions, and (3) iatrogenic lesions. Space occupying lesions can be benign or malignant. Almost any pelvic mass can potentially result in neural compression; however certain lesions have a predilection for causing neural compression because of their anatomical location. Certain pelvic nerves can be susceptible to compression at particular anatomical bony or fibrous canals. Other nerves can be placed at risk during certain surgical procedures, or can be susceptible to traumatic injury because of their proximity to commonly fractured or avulsed osseous or tendinous structures. Relatively common benign lesions that can potentially cause a compressive neuropathy include, ganglion cysts, perineural cysts and fluid filled bursae. Para labral cysts of the hip should be specifically noted, as they might decompress anteriorly resulting in obturator nerve compression, or posteriorly compromising the sciatic or superior gluteal nerve [6, 7] (Fig. 7). Communication with the hip joint should always be considered when a cystic lesion in these locations is encountered, particularly as paralabral cysts may grow to a very large size and appear to be remote from the hip. Malignant lesions encompass any malignant pelvic soft tissue masses, including gynecological and rectal tumors, bone and lymph node metastases. Nerve sheath tumors may be benign or malignant, but are more commonly benign, and have quite characteristic imaging appearances, manifested by markedly hyperintense T2 signal, sometimes associated with a target sign, and avid enhancement [8]. The orientation along the long axis of a peripheral nerve and the presence of distal muscular atrophy are other useful signs suggestive of a neurogenic tumor [9]. Post-traumatic lesions include direct traumatic injury, where the more superficially located femoral and sciatic nerves are at greater risk. Nerve impingement may also occur in the setting of healed fractures, remote avulsion injuries and heterotopic ossification. The obturator nerve is particularly susceptible in the setting of pubic rami and pelvic fractures while the superior gluteal nerve may be injured after hip fracture [10]. Traumatic hamstring tendon avulsion from the ischial tuberosity may result in sciatic neuropathy. The anterior branch of the obturator nerve may be affected by adductor brevis tendinopathy [11]. Traction related indirect nerve injury, particularly to the sciatic, femoral and obturator nerves, during abdominal, hip and genitourinary surgery might range from subclinical to clinical but often resolves spontaneously. Direct iatrogenic injury of pelvic nerves can also occur during pelvic surgery, with the obturator nerve being particularly susceptible during genitourinary surgery (e.g., hysterectomy and prostatectomy) [12] (Fig. 8). The femoral nerve might be injured following vascular intervention in the groin, either directly while accessing the femoral artery, or indirectly by hematoma or pseudoaneurysm complicating the procedure. Neuropathy of the superior gluteal nerve is a recognized, relatively common, complication of total hip arthroplasty [13, 14], and there have been case reports of femoral and obturator neuropathy due to cement extrusion [15]. Like any peripheral nerve, the nerves of the pelvis and lumbosacral plexus may also become affected by neuritis or neuropathy in the absence of a compressive lesion or injury. This may be infectious or inflammatory in origin, and is most commonly seen in the setting of systemic disease, following viral infections (chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy) and pelvic irradiation. Neuropathy with secondary muscular denervation in the clinical setting of diabetes mellitus is a well-recognized phenomenon (diabetic amyotrophy), and has a particular predilection for the lumbosacral plexus [3]. Hereditary neuropathies can also occur, most notably Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease or hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN).