Fig. 10.1

Patent urachus. (a) Ultrasonography demonstrates a tubular structure (arrow) located in the midline. (b) In the sagittal plane, the structure extends from the bladder dome to the umbilicus. There is expansion in the cranial direction (left side of the image) and a hyperechoic structure at this site. (c) Axial plane near the umbilicus demonstrates an expanded patent ductus urachus. Fatty tissue around the duct is inflamed. A calculus (arrow) can also be seen

Sinography

May be used to demonstrate the tract in cases of patent urachus or if there is an active periumbilical discharge

Computed Tomography

Computed tomographic findings are similar to ultrasound.

A tubular, fluid-containing tract extending from the bladder to the umbilicus (patent urachus), a cystic lesion in patients with urachal cyst and diverticular extension from the dome of the bladder or from the umbilicus in umbilical-urachal sinus, and vesicourachal diverticula can be demonstrated on CT.

In case of an infection, increased wall thickness and increased attenuation compared to water density may be present (Fig. 10.2a, b).

Fig. 10.2

Patent urachus. (a) Enhanced CT examination demonstrates a tubular, fluid-filled structure in the midline, in front of the bladder, behind rectus muscle (arrow). This finding is consistent with patent urachus. (b) Inflammation of the duct may lead to an increase in wall thickness (arrow) and calcification (arrowhead)

If malignancy arises in a urachal remnant, a heterogeneously enhancing mass lesion with areas of low attenuation (due to mucin content) can be demonstrated. Calcifications are evident in 50–70 % of urachal carcinomas.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Multiplanar capabilities of MRI may be useful to demonstrate the relationship of a urachal remnant to the urinary bladder.

Diffusion-weighted MRI reveals hindered diffusion in the fluid component of urachal cysts.

Pathology

In the early fetal stage, the urachus connects the apex of the bladder to the allantois, located at the umbilicus.

Failure of obliteration of the urachus, which usually occurs by the fourth month in utero, produces several malformations, which may be complicated by abdominal pain, chronic drainage from the umbilicus, infection, abscess formation, or stone formation.

Completely patent urachus, evident at birth, denotes free communication between the bladder and the umbilicus, with drainage of urine via the umbilicus.

Alternating urachal sinus, which presents after the neonatal period, is a variant of completely patent urachus in which loculated infections developing in potential spaces along the course of the urachus eventually drain into the bladder and via the umbilicus.

Incompletely patent urachus may manifest as a blind urachal cyst, closed at each end of the urachus; an umbilicourachal sinus, closed at the bladder end and patent at the umbilical end; or a vesicourachal sinus or diverticulum, patent at the bladder end and closed at the umbilical end (Figs. 10.3 and 10.4). Urachal cysts are lined by urothelium, by glandular epithelium, or by flat cuboidal epithelium (Fig. 10.5).

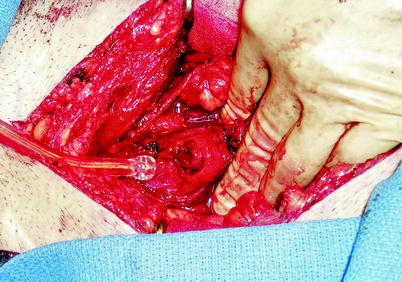

Fig. 10.3

Urachal cyst. This urachal cyst in the bladder dome was unroofed during cystoscopy to evaluate microhematuria in a 45-year-old man, and then subsequently resected surgically, as shown in this image. It was unclear whether the cyst had an established pre-existing communication with the bladder lumen (Photo courtesy of Tom Leininger, M.D.)

Fig. 10.4

Urachal cyst. Urachal cyst and urachal tract to the level of the umbilicus were resected (Photo courtesy of Tom Leininger, M.D.)

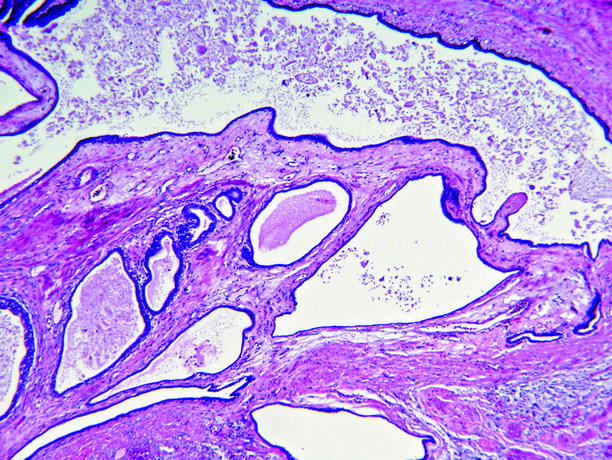

Fig. 10.5

Urachal cyst. The cyst has a complex architecture. The lining epithelium is cytologically benign; it is predominantly flat cuboidal epithelium, interspersed with glandular-type epithelium

Urachal adenocarcinoma is considered to be an entity distinct from adenocarcinoma arising in bladder mucosa.

Diagnostic criteria are strict:

It must be located in the dome of the bladder.

There must be no cystitis glandularis or intestinal metaplasia in the adjacent bladder mucosa.

There should be an abrupt transition from normal urothelium to adenocarcinoma (Fig. 10.6).

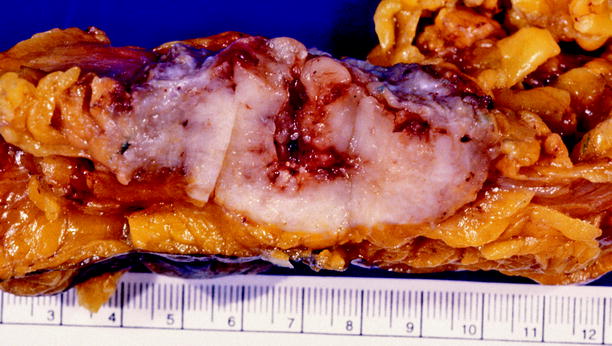

Fig. 10.6

Adenocarcinoma of urachus. Tumor was in the dome of the bladder. The adjacent bladder epithelium showed no abnormalities. No intestinal lesions were present

In addition, origin from an adjacent organ such as colon must be excluded.

A variety of histologic patterns may be evident microscopically; mucinous (colloid) carcinoma is most common, but other types include enteric type, signet ring cell type and adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (Fig. 10.7).

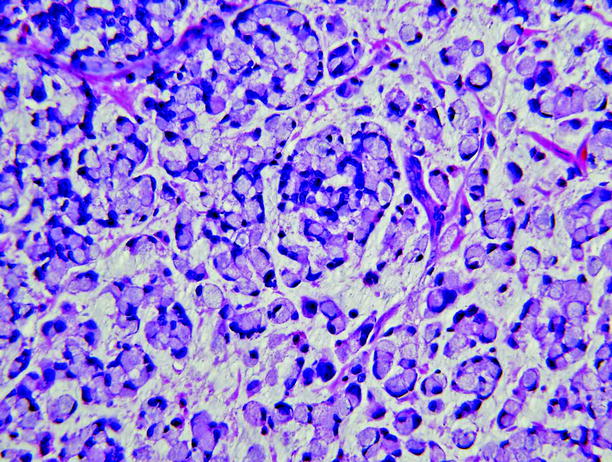

Fig. 10.7

Adenocarcinoma of urachus. The tumor was a mixture of mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell-type adenocarcinoma

Differential Diagnosis

Omphalitis

Granulation tissue at the umbilical stump

Bladder diverticula

Pearls and Pitfalls

Patent urachus is generally symptomatic in the neonatal period. The other urachal abnormalities may present as incidental imaging findings in an adult.

Of the urachal remnant anomalies, urachal cysts are the last to present with symptoms.

Patients with urachal remnants may present with urinary infection, periumbilical fluid discharge, or a palpable lower abdominal mass.

Ultrasonography is the first choice of imaging due to the lack of radiation and also very high detection rates with high frequency transducers.

A solitary bladder diverticulum at the anterosuperior wall of the bladder should raise the suspicion for a vesicourachal diverticulum, as this is not a typical location for acquired bladder diverticula.

The development of malignancy in urachal remnants is rare. Such malignancies account for less than 1 % of bladder cancers, and 90 % of them arise in the juxtavesical portion of the urachus.

Bladder Herniation

General Information

A portion of the bladder is involved in 1–4 % of inguinal hernias.

The involvement rate is higher in men older than 50 years (10 %).

The bladder can also be herniated through the femoral canal.

Only 10 % of all bladder hernias are diagnosed preoperatively.

Imaging

Plain Film Radiography

Increased soft tissue density in the inguinal and/or scrotal region

Intravenous Pyelography

Lateral displacement of the lower 1/3 of one or both ureters

Small, asymmetrical bladder

Incomplete visualization of the bladder base

Hydronephrosis if obstruction is present

Cystography

Dumbbell-shaped bladder: Part of the bladder in the pelvis and part in the hernial sac extending to the scrotum

Ultrasound

Cystic structure inside inguinal canal communicating with the bladder (Fig. 10.8a).

Fig. 10.8

Herniation of the bladder to the inguinal canal. Transabdominal ultrasound (a), corresponding sagittal CT (b), and 3D-reconstruction CT (c) demonstrate bladder herniation (arrows)

The size might increase with Valsalva’s maneuver (due to increased intra-abdominal pressure).

Hernias can be reduced spontaneously or by external manipulation.

Rarely can extend to the scrotum (scrotal cystocele).

Computed Tomography

Visualization of a portion of the bladder inside the inguinal or femoral canal.

Displacement of the ureter.

Multiplanar reformations or three-dimensional reconstructions might be useful to demonstrate the connection of the cystic structure with the bladder (Fig. 10.8b, c).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Similar to CT findings

Differential Diagnosis

Inguinal hernia

Rare cases of herniation (herniation of mesenteric duplication cyst, synovial cyst, ovarian cyst)

Pearls and Pitfalls

Benign prostatic hypertrophy, because it is a chronic and progressive cause of bladder outlet obstruction, might play a role in the etiology of herniation by contributing to the formation of bladder diverticula, or by causing chronic bladder distension due to failure to empty the bladder completely with voiding, or by necessitating abdominal straining and increased intra-abdominal pressure to accomplish voiding.

Preoperative imaging should always be used in men older than 50 years, presenting with inguinal hernia and obstructive lower urinary tract symptoms (nocturia, frequency, dysuria).

Double micturition due to a delay in the emptying of the herniated portion is also an important symptom.

In some cases, the hernia might be visible only when the patient is standing upright, so IVP (an examination performed in supine position) might be uninformative, but voiding cystourethrography in the same patient might demonstrate the pathology.

A narrow entrance to the herniated portion may prevent passage of the contrast medium to the herniated segment, preventing its visualization.

Valsalva’s maneuver should be used in sonographic examination.

Potential complications of bladder herniation include stone formation, strangulation with necrosis and perforation, vesicoureteral reflux (due to the displacement of the vesicoureteric-insertion angle), and hydronephrosis.

Bladder Diverticulum

General Information

A diverticulum is an outpouching of the bladder mucosa and submucosa through the muscular layer. It is more frequent in men older than 50 years, and male-to-female ratio is 9:1.

It is generally asymptomatic.

The male dominance is mainly due to the presence of benign prostatic hypertrophy, an important cause of bladder output obstruction and increased intravesical pressure.

Most bladder diverticula are acquired.

Upper neuron-type neurogenic bladder is another less frequent etiology.

Certain clinical syndromes are associated with multiple bladder diverticula (Williams, Prune belly, Ehlers-Danlos, Menkes syndromes).

Due to urinary stasis, diverticula sometimes contain urinary stones.

Chronic stasis may contribute to the development of malignancy, but the validity of this hypothesis is unproven.

Imaging

Intravenous Pyelography

Contrast-filled single or multiple outpouchings near the bladder.

Filling defects might be present if there is stone formation or neoplasm inside the diverticula.

Cystography

Contrast filled outpouchings with/without filling defects (Fig. 10.9)

Fig. 10.9

Bladder diverticula. Cystography demonstrates the presence of a diverticulum at the upper-left portion of the bladder as a contrast-filled outpouching

Ultrasound

The bladder wall may be thickened and trabeculated (due to outlet obstruction).

Anechoic cystic structure near the bladder.

The communication with the bladder (the neck of the diverticulum) should be demonstrated to differentiate from other cystic masses (Fig. 10.10).

Fig. 10.10

Bladder diverticula. (a) Gray-scale ultrasound demonstrates a small, tubular bladder diverticula, with a narrow neck. (b) A large diverticula

Diverticular outpouching may contain stones (hyperechoic structure with acoustic shadowing), hematoma (heterogenous avascular echogenicity), or neoplasm.

Doppler ultrasound may demonstrate the presence of a diverticular jet between the bladder and the diverticulum. Diverticular jet refers to “to-and-fro” flow between the diverticulum and bladder that can be demonstrated on color flow Doppler ultrasound. The jet may be periodic, due to the pulsations of the iliac artery.

Computed Tomography

CT can demonstrate outpouchings with fluid density. The neck might not be visible if it is very narrow.

If contrast material has been administered, delayed images may demonstrate filling of the diverticulum.

Neoplasms may be recognizable as mucosal thickenings or as enhancing mass lesions (Fig. 10.11).

Fig. 10.11

Neoplasia in bladder diverticula. CT examination demonstrates an enhancing mass lesion within a bladder diverticula at the left base of the bladder. Pathologic examination revealed the mass to be transitional cell carcinoma (Courtesy of Prof. Dr. Arzu Armagan Poyanlı, Istanbul University, Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Department of Radiology)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree