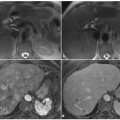

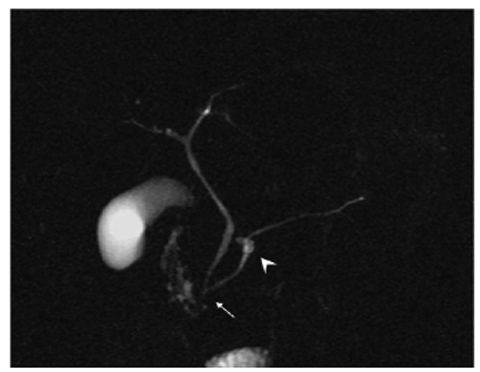

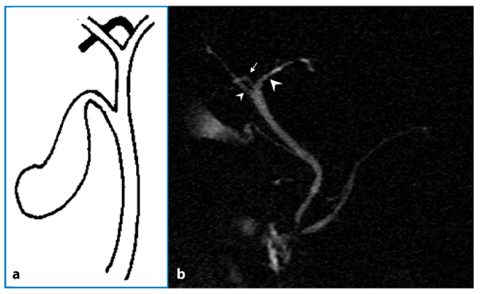

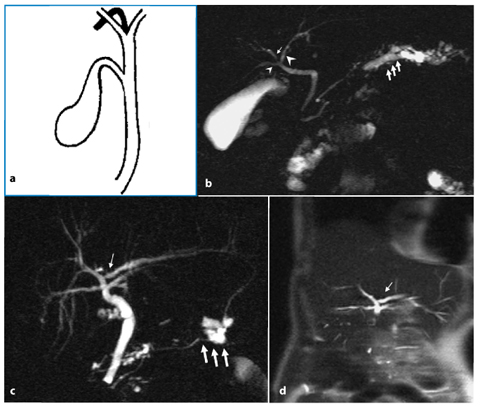

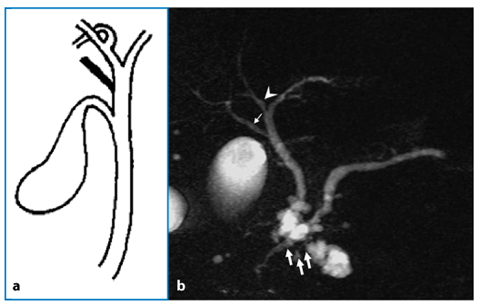

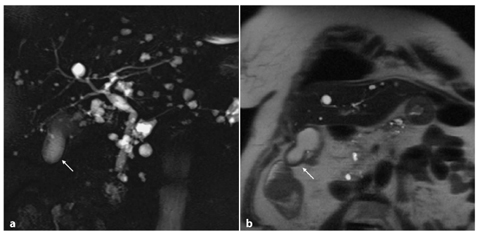

Fig. 2.1

Normal anatomy of the intrahepatic biliary drainage system. a Schematic drawing of normal hepatic biliary segmental anatomy. b A projective magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows normal confluence (arrow) of the right posterior hepatic duct and right anterior hepatic duct with a left (medial) approach. Note the normal fusion of the draining duct of segment I (arrowhead) with the left hepatic duct. Note the normal lateral insertion of the cystic duct (double arrows) into the extrahepatic bile duct approximately halfway between the porta hepatis and the ampulla of Vater. Note the normal aspect of the main pancreatic duct draining into the papilla major (dw) and the duct of Santorini draining into the papilla minor (ds)

The individual biliary drainage system is parallel to portal venous supply. The right hepatic duct has two major branches: a posterior or dorso-caudal branch draining the posterior segments (VI and VII), with an almost horizontal course, and an anterior or ventrocranial branch draining the anterior segments (V and VIII), with a more vertical course. The right posterior duct usually runs posterior and fuses with the right anterior duct from a left (medial) approach to form the right hepatic duct. The left hepatic duct is formed by segmental tributaries draining segments II–IV. The bile duct draining the caudate lobe usually joins the origin of the left or right hepatic duct [1].

The common hepatic duct is the portion of the bile duct above the cystic duct and below the bifurcation. It is formed by fusion of the right hepatic duct, which is usually short, and the left hepatic duct, and they usually join up just outside the porta hepatis (±1 cm below the edge of the liver).

Familiarity with segmental hepatic biliary anatomy is essential for both staging and localization of intrahepatic liver neoplasms and bile duct tumors, before hepatic lobectomy or segmentectomy, and before percutaneous or endoscopic interventions, to determine the most appropriate approach and to assess the extent of the disease [1].

2.1.3 Anatomy of the Gallbladder, Cystic Duct and Common Bile Duct

The gallbladder (vesica fellea) is a pearshaped hollow viscus located in a fossa on the lower surface of the liver, between the right lobe and the quadrate lobe. It usually measures 10 cm in length, with a diameter ranging from 3 to 5 cm, and its wall is less than 3 mm thick [7]. The gallbladder is divided into four parts: the fundus, which is the part that is palpable in vivo and usually projects beyond the inferior border of the liver; the body, which is the part in contact with the second portion of the duodenum and the colon; the infundibulum, or Hartmann’s pouch, located at the free edge of the lesser omentum bulging toward the cystic duct; and the neck, which is the part between the body and the cystic duct. The gallbladder should be imaged after the patient has fasted for 8–12 h, as this promotes its physiological distention. During fasting, water is reabsorbed and the concentration of cholesterol and bile salts increases, leading to a shortened T1-relaxation time. A layering effect is sometimes observed, with concentrated and denser bile in the dependent position. The gallbladder wall has low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images, and is enhanced uniformly after the administration of gadolinium-based contrast material. Normal bile appears uniformly bright on T2- weighted sequences, while on T1-weighted images it varies greatly in signal intensity depending on its concentration [7].

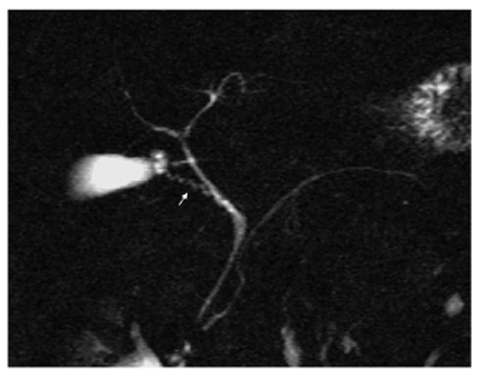

The cystic duct connects the gallbladder to the extrahepatic bile duct and its point of insertion into the extrahepatic bile duct marks the division between the common hepatic duct and the common bile duct [8]. The cystic duct usually joins the common hepatic duct into the right side at a certain angle, coursing to the right of the hepatic artery, approximately halfway between the porta hepatis and the ampulla of Vater (Fig. 2.1b). The cystic duct usually measures 2–4 cm in length, with a diameter ranging from 1 to 5 mm, and it contains prominent concentric folds known as spiral valves of Heister (Fig. 2.2) [8]. The insertion of the cystic duct into the hepatic duct can be demonstrated with routine T2-weighted imaging, and MRCP.

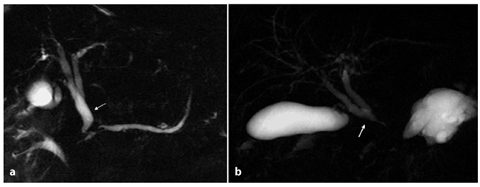

Fig. 2.2

Normal cystic duct anatomy. A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows that the cystic duct connects the gallbladder to the extrahepatic bile duct, approximately halfway between the porta hepatis and the ampulla of Vater. Note the undulating contour of the duct produced by the valves of Heister (arrow)

The common bile duct is the portion above the papilla and below the cystic duct; it has a mean diameter of 5 mm for patients up to the age of 50 years, and increases 1 mm per decade thereafter. The course of the normal common bile duct is through the pancreatic parenchyma (65% of patients), in a groove in the posterior aspect of the pancreatic head (25% of patients), and posterior to the pancreatic head and totally extrapancreatic (10% of patients). If the distal common bile duct courses through the pancreatic parenchyma, it may be smaller in diameter than the suprapancreatic portion [9].

2.1.4 Pancreas and Vaterian Sphincter Complex

The pancreas is a retroperitoneal lobulated organ that extends transversely across the abdomen from the concavity of the duodenum to the spleen, and crosses the lumbar spine at approximately the level of the first and second lumbar vertebrae. The gland can be divided into four parts: head, neck, body and tail. The head is located to the right of the superior mesenteric vein, within the curve of duodenum. The uncinate process is a prolongation of the caudal part of the head, and has a triangular appearance. The pancreatic neck is the portion to the left of the head and ventral to the superior mesenteric vein. The border between the body and tail is not clearly defined, but can be determined using one-half of the distance between the neck and the end of the pancreas [2].

The main pancreatic duct usually measures 9.5–25 cm in length, with maximal anteroposterior diameters of the head, body and tail of 3.5 mm, 2.5 mm and 1.5 mm, respectively. It terminates at the major papilla in the duodenum, and the common types of course are a „sigmoid” configuration (ascending-horizontal-ascending) or a „pistol” configuration (ascending-horizontal-horizontal) [4, 9]. This principal duct drains the greater part of the gland. As a rule, only a small upper anterior part of the head uses the accessory pancreatic duct (of Santorini), which enters the duodenum at the small accessory papilla (Fig. 2.1b). The accessory duct usually communicates with the main pancreatic duct within the head of the pancreas, and has a small diameter, usually 1 mm less than the diameter of the duct of Wirsung [6]. The side branches of principal duct, usually between 15 and 30 in number, appear at regular intervals in the body and tail, and they are variable in number, length and caliber in the pancreatic head.

Because the pancreatic duct is curved and oblique, it is not usually seen in its entirety on a single source image; however, the entire length can usually be evaluated when reviewing sequential images. When half-Fourier pulse sequences are used, the main pancreatic duct in the head, body and tail can be seen in up to 97%, 97% and 83% of cases, respectively [2]. However, because of a decrease in spatial resolution, the pancreatic side branches are seen less frequently, with secondary branches in the head, body and tail seen in 19%, 10% and 5% of cases, respectively. Because imaging is performed in the physiological non-distended state, non-visualization of the duct at MRCP does not necessarily indicate disease [2]. The evaluation of normal or less abnormal pancreatic ducts remains crucial, and dynamic MRCP after secretin stimulation has shown a significant improvement in visualization of the main pancreatic duct and image quality of the normal pancreatic duct [10].

The pancreatic and common bile ducts join within the wall of the duodenum and have a short common terminal portion, which usually measures 2–15 mm (mean 5 mm) in length. In some cases, each duct has its own opening either at the papilla or occasionally at some distance, and this can be as much as 2 cm. The slightly dilated distal segment of the common channel is also called the ampulla. The Vaterian sphincter complex includes the intramural part of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct, the papilla and the surrounding smooth muscle (sphincter of Oddi); it usually measures 10–15 mm in length and has an oblique course. The papilla forms an endoluminal protrusion at the medial wall of the duodenum and contains the orifice. The papilla is usually located at the posteromedial wall of mid-descending duodenum and has a length of less than 10–15 mm. The junction between the distal common bile duct and the pancreatic duct can be classified as follows: Y-type junction (approximately 70% of cases) (Fig. 2.3), V-type junction (approximately 20%), U-type junction (approximately 10%), or another type. The location of the minor papilla is 1–2 cm proximal to the major papilla, where the accessory pancreatic duct of Santorini empties into the duodenum [9].

Fig. 2.3

Y-type junction. A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows the most common type of junction (arrow) between the distal common bile duct and the pancreatic duct (Y-type junction). Note the multiple cystic dilatations (arrowhead) of side branches in the body of the pancreas (multifocal intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm)

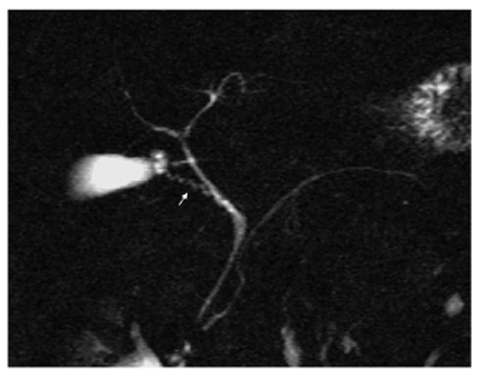

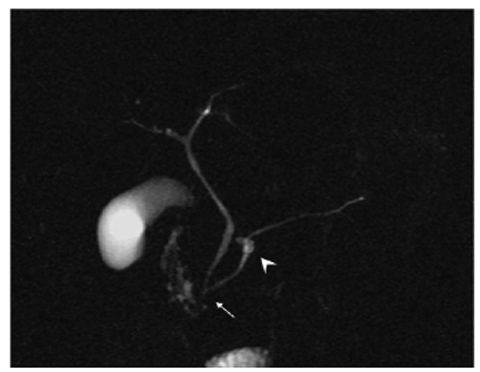

The most distal portions of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct may be difficult to evaluate with MRCP. In fact, the non-visualization of the Vaterian sphincter complex may be related to the small size of the intrasphincteric portion of the ducts or the contractile activity of the sphincter, and this may lead to false-negative results. With repetitive single- shot MRCP, the Vaterian sphincter complex can be examined several times within a short time window, and changes in morphology can be assessed (Fig. 2.4) [11].

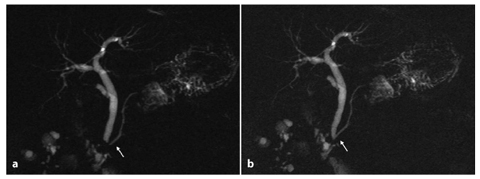

Fig. 2.4

Functional activity of the Vaterian sphincter complex. a, b Projective images with an interval of 30 s. a A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) image shows an invisible common bile duct (arrow). b An MRCP image taken 30 s later shows the Vaterian sphincter complex clearly (arrow). Result of cholecystectomy

2.2 Anatomical Variants of the Intrahepatic and Extrahepatic Biliary Tree

Anatomical variations are defined as anomalies in the course of the bile ducts that are generally asymptomatic, even though they may predispose to pathological conditions, and make up a wide and complex spectrum of entities that are frequently encountered at MRCP [12]. There are as many as 24–57% of individuals with variant biliary patterns [13]. Defining these anatomical variations before surgery is crucial to reducing both the risk of complication and the operating time [14].

2.2.1 Common Anatomical Variants of the Intrahepatic and Extrahepatic Biliary Tree

As reported in the literature, the most common anatomical variants in the branching of the biliary tree involve the right posterior duct (draining the VI and VII hepatic segments) and fusion with the right anterior or left hepatic duct. Normally, the right posterior duct passes posteriorly to the right anterior duct and joins it from the left to form the right hepatic duct [1].

In 13–19% of the population, the most common anatomical variant of the biliary system is the drainage of the right posterior duct into the left hepatic duct before its confluence with the right anterior duct (also known as crossover anomaly) (Fig. 2.5) [1, 4, 12].

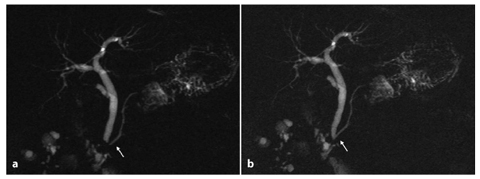

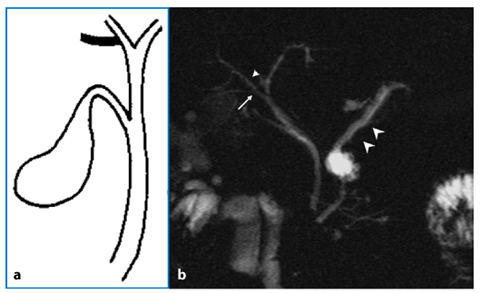

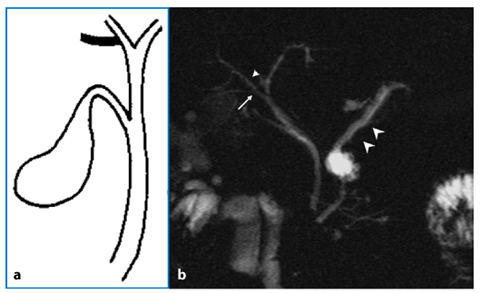

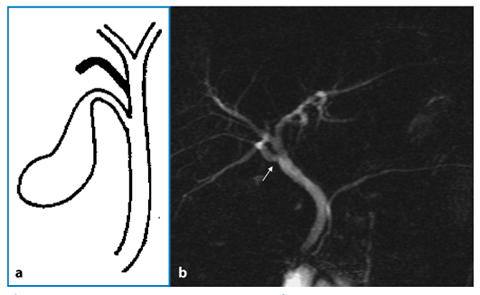

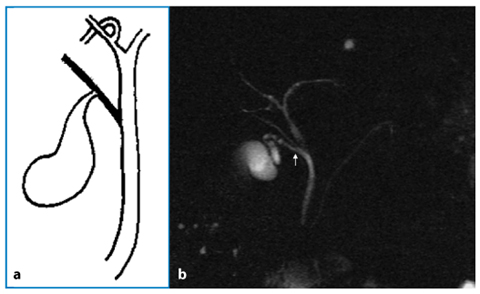

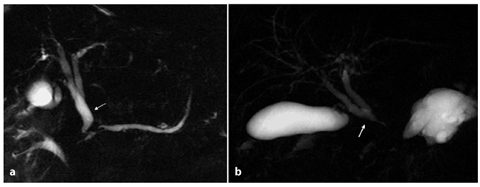

Fig. 2.5

Crossover anomaly. a Schematic drawing. b A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows the emptying of the right posterior duct (arrow) into the left hepatic duct (large arrowhead) before joining the right anterior duct (small arrowhead)

In 12% of the population, the right posterior duct does not pass the right anterior duct posteriorly, but empties into the right aspect of the right anterior duct (Fig. 2.6) [1, 4, 12].

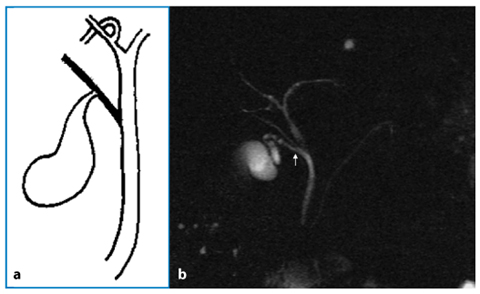

Fig. 2.6

Right posterior duct. a Schematic drawing. b A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows the emptying of the right posterior duct (arrow) into the right anterior hepatic duct (small arrowhead), viewed from the right side. Note the cystic serous neoplasm in the body of the pancreas, and the dilatation of the main pancreatic duct in the body and tail; these are manifestations of chronic pancreatitis (large arrowheads). Result of cholecystectomy

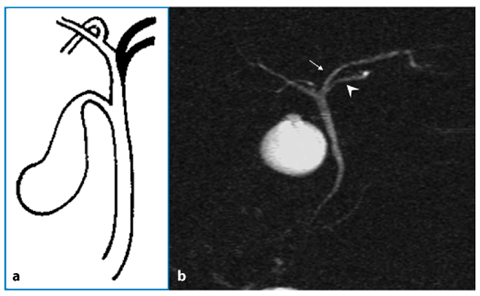

Another common variant (11% of cases) of the main biliary branching is the so-called triple confluence (Fig. 2.7), which is an anomaly characterized by simultaneous emptying of the right posterior duct, right anterior duct and left hepatic duct into the common hepatic duct. In patients with this variant, the right hepatic duct is virtually non-existent [1, 4, 12].

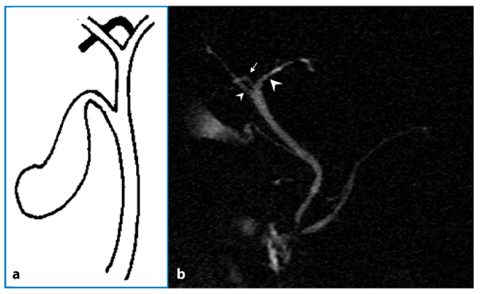

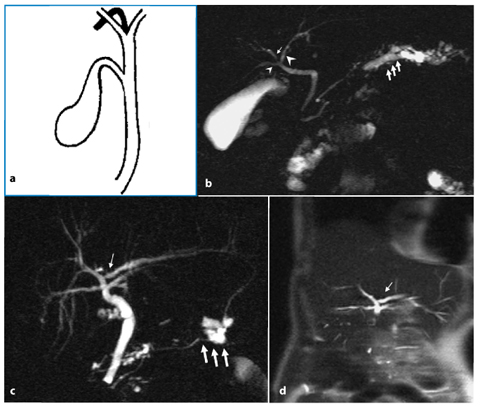

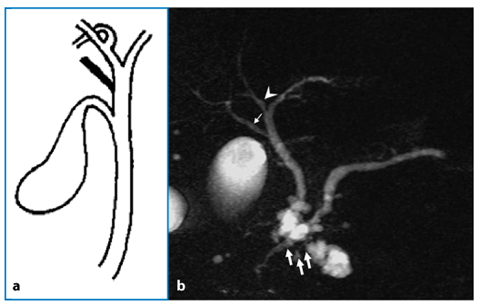

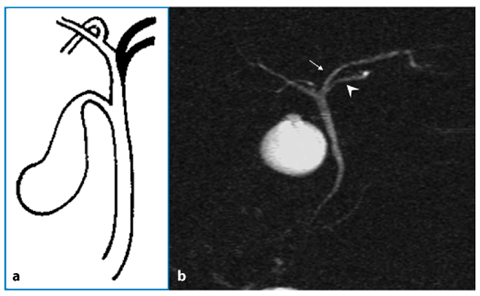

Fig. 2.7

Triple confluence. a Schematic drawing. b Case 1. A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) image shows triple confluence of the right anterior duct (small arrow), the right posterior duct (small arrowhead) and the left hepatic duct (large arrowhead). Note the dilatation of the main pancreatic duct and side branches (large arrows) in the tail of the pancreas; these are manifestations of chronic pancreatitis. c, d Case 2. c An MRCP image shows triple confluence of right anterior, right posterior and left hepatic ducts. Note the drainage of an accessory left hepatic duct (small arrow) into the anterior right hepatic duct. Result of cholecystectomy. Note the cystic serous neoplasm in the tail of the pancreas (large arrows). d Coronal half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo (HASTE) T2- weighted image confirms the presence of the triple confluence of right anterior, right posterior and left hepatic ducts, and an accessory left hepatic duct (arrow) draining into the anterior right hepatic duct

2.2.2 Uncommon Anatomical Variants of the Intrahepatic and Extrahepatic Biliary Tree

Several less common and usually more complicated anatomical variations of the bile duct have been described, and these consist of both aberrant and accessory bile ducts [1]. In 5% of the population, the right posterior duct flows into the common hepatic duct on the right side; in 1% of the population it flows into the common hepatic duct on the left side, and this is an important variant also known as the aberrant hepatic duct (Fig. 2.8) [1, 4]. An additional bile duct draining the same area of the liver is observed in approximately 2% of patients, and this may originate from and run its course along both the left and the right ductal systems. This variant is also known as an accessory hepatic duct (Figs. 2.7c, d and 2.9) [1, 15].

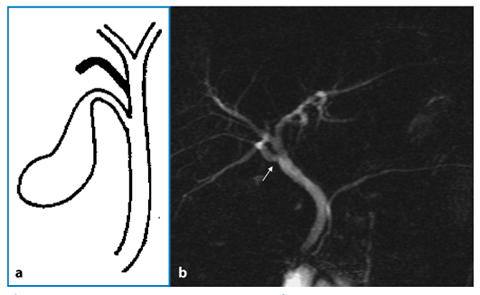

Fig. 2.8

Aberrant hepatic duct. a Schematic drawing. b A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows drainage of the right posterior duct (arrow) into the common hepatic duct from the right side, a variant also known as the aberrant hepatic duct. Result of cholecystectomy

Fig. 2.9

Accessory right hepatic biliary duct. a Schematic drawing. b A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows drainage of an accessory right hepatic duct (small arrow) into the common hepatic duct from the right side. Note the normal confluence (arrowhead) of the right posterior hepatic duct and right anterior hepatic duct with a left (medial) approach. Note the multiple cystic dilatations (large arrows) of side branches in the head of the pancreas (multifocal intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm). Result of cholecystectomy

An aberrant or accessory right hepatic biliary duct emptying into the cystic duct is also an uncommon anatomical variation (Fig. 2.10) [1, 8, 15]. An accessory hepatic duct might also run through the gallbladder bed and can sometimes even enter the gallbladder itself [6]. Other exceedingly rare variations in bile duct branching can be seen and these may range from unique solitary findings to extensively complicated anatomy, including segments II and III of the left hepatic duct draining individually into the right hepatic duct (Fig. 2.11), the quadrifurcation of the right or main hepatic duct (Fig. 2.12), unusually large right or left segmental branches, and a lower location of the bifurcation of right and left hepatic ducts. In individuals with low union or non-union, the cystic duct drains into the right hepatic duct (Fig. 2.13) [1, 9].

Fig. 2.10

Accessory right hepatic biliary duct. a Schematic drawing. b A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows drainage of an accessory right hepatic duct (arrow) into the cystic duct

Fig. 2.11

Segments II and III of the left hepatic duct. a Schematic drawing. b A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows segment II (arrow) and segment III (arrowhead) draining individually into the right hepatic duct

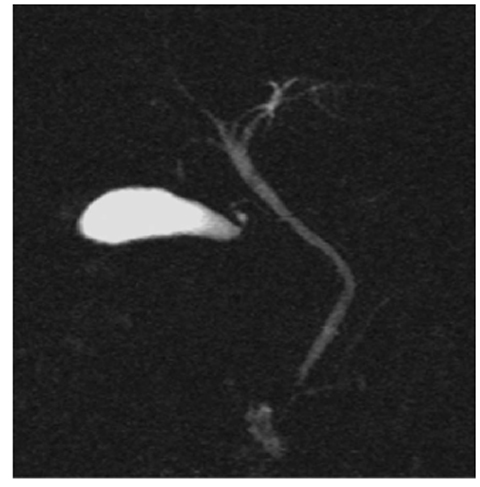

Fig. 2.12

Quadrifurcation. A projective magnetic res – onance cholangiopancreatography image shows the quadrifurcation of main hepatic duct, an exceedingly rare variation

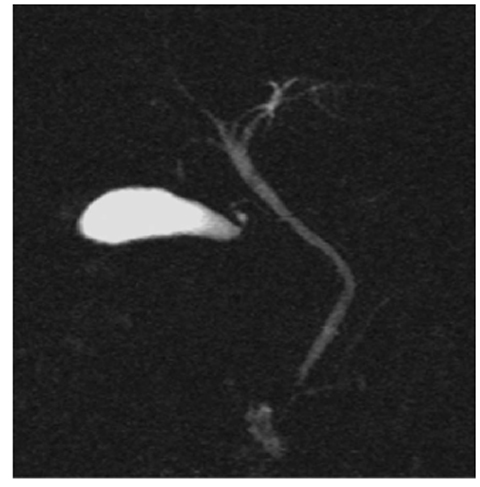

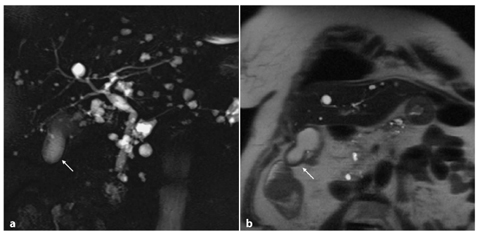

Fig. 2.13

Low bifurcation of the right and left hepatic ducts. a A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows a low bifurcation (arrow) and the cystic duct draining into the bile duct just below the bifurcation. b Another case of low bifurcation. The cystic duct drains into the right hepatic duct (arrow)

In extremely rare cases, the right and left ducts drain separately into the duodenum [1, 9]. Congenital doubling of the extrahepatic biliary tract is extremely rare with sporadic cases reported, and it consists of a common bile duct with a septum within the lumen, a common bile duct that bifurcates with two independent drainages, double biliary drainage without any direct communication, or double biliary drainage with one or more communicating channels [16].

A consequence of the development of fetal obstructive cholangiopathy is atresia of the biliary pathways, and this can be extrahepatic or intrahepatic. This is the most frequent indication for liver transplantation in children [12].

Anomalous or aberrant bile ducts are usually of no clinical significance, unless they lead to diagnostic confusion on imaging studies or result in increased potential for iatrogenic injury [8]. Aberrant or accessory biliary ducts may predispose patients to inadvertent ductal ligation at laparoscopic cholecystectomy and may complicate surgery, such as living donor right lobe liver transplantation.

Ducts at greatest risk for injury at cholecystectomy are those that course near the cystic duct or gallbladder or empty directly into these structures, and all may disorient the surgeon [8]. Failure to recognize these anatomical variants may result in inadvertent ductal ligation, biliary leaks, strictures, partial liver atrophy, biliary cirrhosis and cholangitis [1, 9, 15].

2.2.3 Biliary Hamartomatosis

Biliary hamartomatosis, also known as the von Meyenburg complex, is a rare benign malformation caused by anomalous development of the bile ducts, and it is characterized by the presence of multiple and diffuse parenchymal nodules, which range from a few millimeters up to 1.5 cm in size (Fig. 2.14) [17]. Using magnetic resonance, the main features of biliary hamartomatosis include parenchymal nodules that are hypointense in T1-weighted images and hyperintense in T2- weighted images, and that show poor and delayed contrast enhancement [12]. Biliary hamartomatosis can be confused with multiple hepatic secondary lesions, metastases, multiple liver micro-abscesses, and Caroli’s disease; a histological examination is necessary for a definitive diagnosis [12].

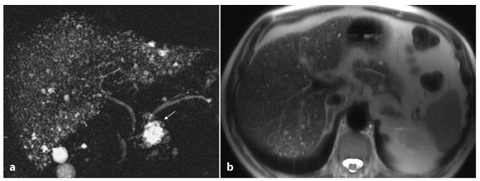

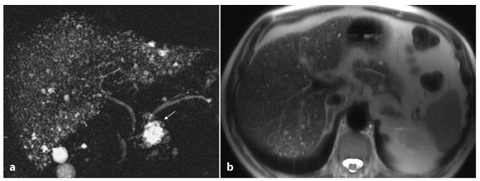

Fig. 2.14

Biliary hamartomatosis (the von Meyenburg complex). a A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows biliary hamartomatosis with multiple and diffuse parenchymal nodules. Note the large cystic serous neoplasm in the head of the pancreas (arrow). Result of cholecystectomy. b An axial half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo (HASTE) T2-weighted image confirms biliary hamartomatosis and parenchymal nodules, which are hyperintense

2.3 Anatomical Variants of the Gallbladder, Cystic Duct and Common Bile Duct

2.3.1 Anatomical Variants of the Gallbladder

Congenital anomalies of the gallbladder are rare and can be accompanied by other biliary and vascular malformations [18].

The „phrygian cap” (folded fundus) deformity is the commonest congenital anomaly of the gallbladder, but it has no pathological significance (Fig. 2.15) [19, 20].

Fig. 2.15

Phrygian cap. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (a) and coronal half-Fourier acquisition single- shot turbo-spin-echo (HASTE) T2-weighted (b) images show a folding fundus with a larger diameter of the distal part and presence of a septum (arrow). Note the multiple hepatic cysts

The gallbladder is attached to the inferior surface of the right and quadrate lobes of the liver. Various anomalous positions of the gallbladder have been reported, including intrahepatic, retroduodenal, retropancreatic, suprahepatic (just inferior to the right hemidiaphragm), extraperitoneal, in the lesser omentum, and within the falciform ligament. Subcutaneous gallbladder herniation through the abdominal wall is rare; also rare is internal gallbladder herniation through the foramen of Winslow. A left-sided gallbladder may be seen in situs inversus, or even, in extremely rare cases, in normal situs [9, 18, 19].

Anomalies in the number of gallbladders are rare, but they have been reported, and range from absent to duplications. Gallbladder agenesis is an anatomical variation with an incidence of 0.01–0.075%, and is usually asymptomatic [21]. The fossa of the gallbladder is commonly absent, but occasionally a shallow fissure or dimple is visible on the under surface of the right lobe [22]. This anatomical variant can be associated with a left-side isomerism (asplenia), an absent cystic duct or other gastrointestinal anomalies, such as duodenal atresia; rarely, it is accompanied by compensatory dilatation of the hepatic or common ducts [22]. A bilobed duplicated gallbladder is a congenital abnormality that is well defined at magnetic resonance imaging. This entity was seen in one of every 4000 adults in an autopsy series, and it predisposes to complications such as cholecystitis and cholelithiasis, and it may be associated with right-upperquadrant pain [7]. Gallbladder duplication is more common in right-sided isomerism (polysplenia). An accessory gallbladder may be adjacent to the normal organ and thus lie in the normal fossa of the gallbladder or in a position other than in the normal fossa, for example under the left lobe, and it may communicate with the left hepatic duct [22]. It is thought to be caused by exuberant budding of the developing biliary tree when the caudal bud of the hepatic diverticulum divides [23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree