Fig. 5.1

Osteoarticular dissection of the hip joint (lateral view). (1) Head of femur. (2) Acetabular fossa or cotyloid fossa, with the pulvinar. (3) Lunate articular surface. (4) Acetabular labrum. (5) Ligamentum teres. (6) Fovea capitis. (7) Capsule of the hip joint (resected). (8) Paralabral sulcus, labrum-capsular sulcus, or perilabral recess. (9) Anterior inferior iliac spine. (10) Rectus femoris tendon cut (reflected and straight heads of the rectus femurs tendon). (11) Greater sciatic foramen. (12) Lesser sciatic foramen. (13) Sacrospinous ligament. (14) Sacrotuberous ligament. (15) Greater trochanter. (16) Lesser trochanter. (17) Ischial tuberosity. (18) Pubic tubercle. (19) Sacroiliac joint. (20) Coccyx

Hip Arthroscopy

Even though arthroscopy of the hip was first performed as early as 1931 [1], its clinical application has developed rather slowly [2, 3]. Clinical assessment of the hip is improving and arthroscopic indications are therefore increasing. As hip arthroscopy becomes more common, it is vital that accurate knowledge of the anatomy of the hip and how to establish the common portals is combined with correct patient selection, sound preoperative planning, and consistent arthroscopic technique in order to maximize clinical outcomes. From an arthroscopic point of view, Dorfmann and Boyer [4] divided the hip into two compartments separated by the acetabular labrum: the central compartment and the peripheral compartment. Recently two new compartments have been described: The peritrochanteric space and the deep gluteal space [5, 6]. The central compartment includes the acetabular fossa, ligamentum teres, lunate cartilage, and articular surface of the femoral head in the weight-bearing area (Fig. 5.2). The peripheral compartment is formed of the non-weight-bearing cartilage of the femoral head, the femoral neck with its synovial folds, and the joint capsule (Fig. 5.3).To access and visualize the central compartment, traction must be applied to the joint, whereas the peripheral compartment is examined better without traction [7]. After releasing traction, flexion of the hip relaxes the anterior capsuloligamentous complex (Fig. 5.4), giving easy access to the anterior peripheral compartment [8].

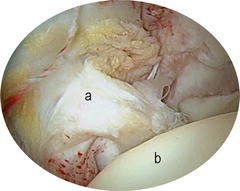

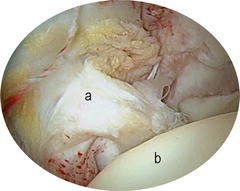

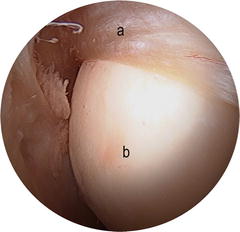

Fig. 5.2

View of the central compartment of the hip: (a) Ligamentum teres (b) Articular surface of the femoral head in the weight-bearing area

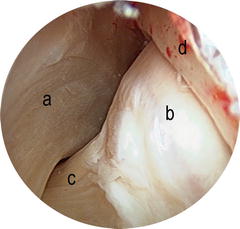

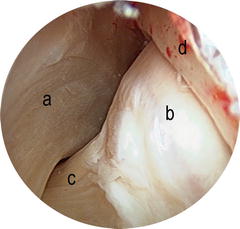

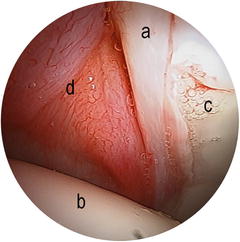

Fig. 5.3

View of the peripheral compartment of the hip: (a) Zona orbicularis (b) Non-weight-bearing cartilage of the femoral head (c) Femoral neck (d) Peripheral labrum

Fig. 5.4

Supine position for hip arthroscopy. Flexion of the hip relaxes the anterior capsuloligamentous complex giving easy access to the peripheral compartment

Intracapsular Anatomy of the Hip and Arthroscopic Hip Examination

Femoral Head

The femoral head forms approximately two thirds of a sphere and is covered throughout with articular cartilage, except at the fovea. Anteriorly, the articular surface extends to the neck. It faces anterosuperomedially and geometrically resembles part of the surface of an ovoid (Fig. 5.5). Kurrat and Oberlander [9] found maximal thickness of the articular cartilage on the anterolateral portion of the femoral head. Normal hyaline cartilage, as in other joints, has a shining white appearance on direct inspection. The only fixed landmark on its surface is the insertion of the ligamentum teres on the fovea (Fig. 5.6). This area is located on the anteromedial portion of the head and was previously known as the bare area.

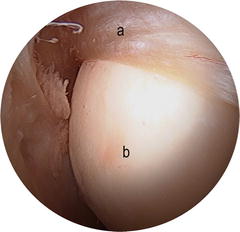

Fig. 5.5

Peripheral compartment viewing superiorly. (a) Anterior labrum. (b) Femoral head resembles part of the surface of an ovoid

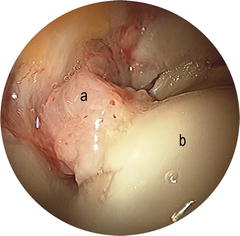

Fig. 5.6

Arthroscopic view of the insertion of the ligamentum teres on the fovea. (a) Ligamentum teres (b) Femoral head

Acetabulum

The horseshoe shape of the acetabulum is a fixed landmark and allows easy orientation within the joint. It can be divided into a superior part, an anterior column, and a posterior column. The inner borders of the articular surface of the acetabulum have a rounded cartilage edge; these form the margins of the acetabular fossa or cotyloid fossa (Figs. 5.7 and 5.8). The thickness of the articular cartilage is reported [9] to be maximal on the anterosuperior quadrant. The acetabulum cartilage can be divided in rim cartilage and non-rim cartilage (Figs. 5.9 and 5.10).

Fig. 5.7

(a) Cotyloid fossa (b) Acetabulum

Fig. 5.8

The central, nonarticular cavity of the acetabulum, often referred to as the cotyloid fossa, contains the pulvinar and ligamentum teres

Fig. 5.9

The acetabulum cartilage can be divided in (a) Non-rim cartilage and (b) Rim cartilage. View of the wave sign at the rim cartilage

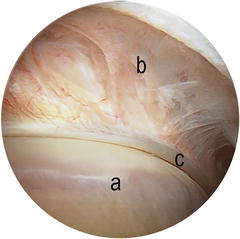

Fig. 5.10

The horseshoe shape of the acetabulum is a fixed landmark and allows easy orientation within the joint. (a) Labrum (b) Rim cartilage (c) Non-rim cartilage

The Acetabular Labrum

The acetabular labrum or cotyloid ligament is found on the rim of the bony acetabulum (Fig. 5.11). The labrum is a fibrocartilage with a triangular cross section; it increases the depth and coverage of the acetabulum, thus favoring stability of the hip joint by forming slightly more than a hemisphere. The labrum has three faces: (1) The base or adherent face is the part that inserts onto the rim of the acetabulum. (2) The internal or articular face is continuous with the articular surface of the acetabulum, such that it is occasionally difficult to distinguish on simple arthroscopic vision (Fig. 5.12). (3) The external face inserts onto the joint capsule, leaving a free border that can be observed during arthroscopic examination (Figs. 5.13 and 5.14). The size of the labrum varies; it is thicker superiorly and posteriorly than it is inferiorly and anteriorly [10, 11]. Classic anatomic studies observed variations of between 6 and 10 mm in the height of the labrum. Average width of the acetabular labrum is reported to be 5.3 mm (SD, 2.6 mm) [12]. In the young adult, the labrum has an avascular, meniscus-like, elastic appearance, whereas in the elderly it can appear yellow and degenerate.

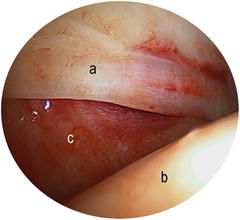

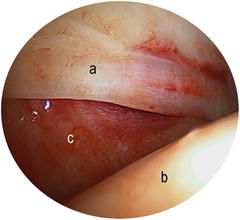

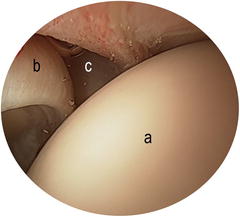

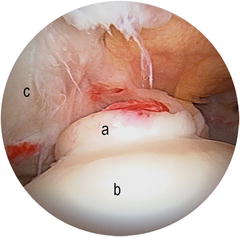

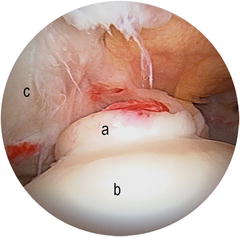

Fig. 5.11

The labrum is a fibrocartilage with a triangular cross section; it increases the depth and coverage of the acetabulum. (a) Labrum (b) Femoral head (c) Anterior capsule

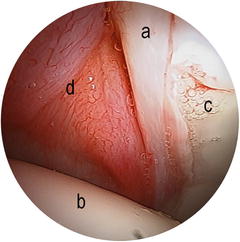

Fig. 5.12

Arthroscopic view of the internal or articular face of the labrum. (a) Labrum (b) Femoral head (c) Acetabulum (d) Anterior capsule

Fig. 5.13

View of the external face of the labrum with traction (a) Labrum (b) Femoral head

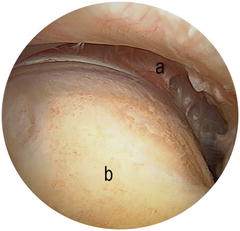

Fig. 5.14

View of the external face of the labrum without traction. The external face of the labrum inserts onto the joint capsule, leaving a free border (a) Femoral head (b) Capsule (c) Labrum

Sometimes the labrum is thin, poorly developed, and hypoplastic, and at other times it may appear enlarged. Superiorly, there is a slight separation between the insertion of the capsule and the acetabular rim, creating a space between the labrum and the capsule known as the paralabral sulcus, labrum-capsular sulcus, or perilabral recess [13] (Figs. 5.15 and 5.16). It is important to get used to the normal arthroscopic appearance of the paralabral sulcus, as certain disorders commonly give rise to adhesions at this site, obliterating the sulcus. On the inner lip of the acetabulum lies the cartilage-labrum junction, which is the most common site for labral pathology. However, it must be remembered that a partial separation of the labrum may be observed at the superior part of the acetabulum as an anatomic variant [14]. This separation is called the sublabral sulcus and should not be confused with a labral lesion. In vivo observation by hip arthroscopy shows the most common site for labral injury to be the anterior and anterosuperior regions [15]. However, the distinction between the sublabral sulcus and a labral lesion is not always clear; a labral lesion should be considered when there are compatible symptoms, or when there is an associated image of labral hemorrhage in acute disorders or granulation tissue indicating attempted healing in chronic disorders [14] (Figs. 5.17 and 5.18).

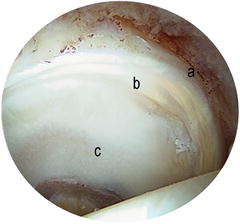

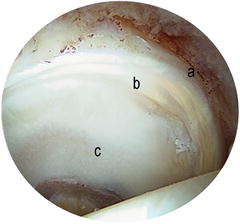

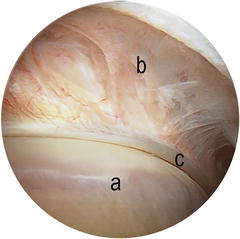

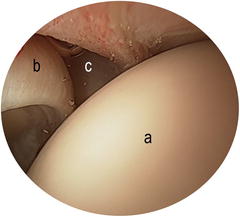

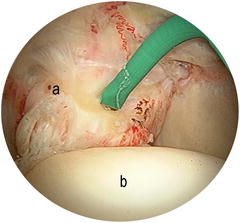

Fig. 5.15

View of a normal paralabral sulcus or perilabral recess (a) Femoral head (b) Labrum (c) Perilabral recess

Fig. 5.16

Arthroscopic view of the peripheral compartment: (a) Superior sulcus above the lateral labrum (b) Femoral neck

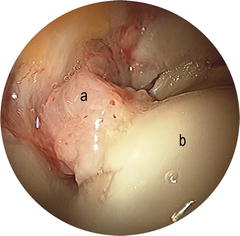

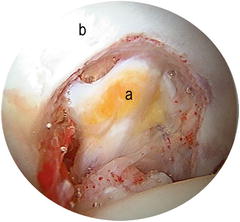

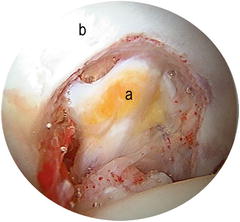

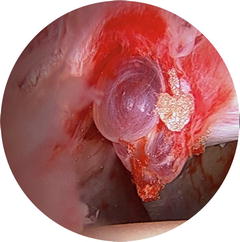

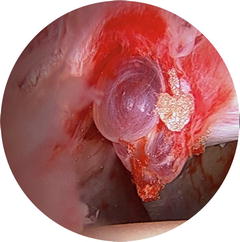

Fig. 5.17

Paralabral cyst an associated labral hemorrhage

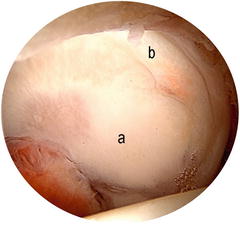

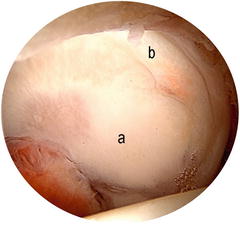

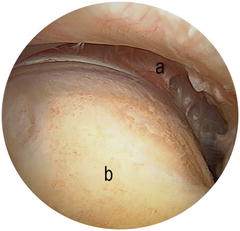

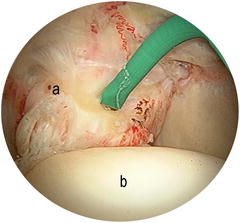

Fig. 5.18

Typical appearance of a labral tear in the anterosuperior weight-bearing zone (a) Labrum (b) Acetabulum

The Ligamentum Teres

The ligamentum teres or ligamentum capitis femoris [16] is an intra-articular ligament that attaches the head of the femur to the acetabulum. It arises in the inferior part of the acetabular fossa and runs inferiorly and anteriorly across the joint space to insert into the fovea capitis of the head of the femur (Figs. 5.19 and 5.20). The ligamentum teres is trapezoid; its base, which is thickened into two bands, inserts onto the border of the acetabular notch and onto the transverse ligament of the acetabulum. As it runs towards the femoral head, it becomes progressively round or oval in shape before inserting into the fovea capitis at a site slightly posterior and inferior to the true center of the head. In cross section, the ligamentum teres is pyramidal, with a fascicular appearance formed by an anterior and a posterior bundle; it follows a spiral course from its acetabular attachment to its femoral insertion. Dynamic hip examination shows that the ligament becomes tense during external rotation of the hip and relaxed on internal rotation. The ligamentum teres may have a function similar to that of the anterior cruciate ligament in the knee [17]. When considering reconstruction of this ligament, anchors should be placed in areas of the acetabulum that provide the best bone stock for purchase, while minimizing the risk of damage to vital intrapelvic structures [18].

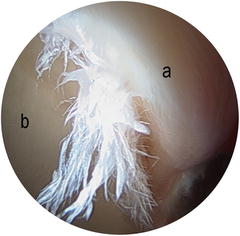

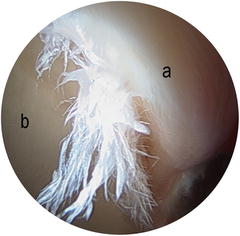

Fig. 5.19

Arthroscopic view of ligamentum teres being probed with a curved radiothermal instrument around the femoral head (a) Ligamentum teres (b) Femoral head

Fig. 5.20

Ligamentum teres, or ligamentum capitis femoris, is an intra-articular ligament that attaches the head of the femur to the acetabulum (a) Ligamentum teres (b) Femoral head (c) Acetabulum

The Synovial Folds

As the neck of the femur is intra-articular, it is covered by synovial membrane. This synovial tissue forms a series of folds that descend along the femoral neck, from the border of the cartilage of the femoral head to the insertion of the joint capsule on the femur. These folds are variable in number and size, and it is important to distinguish them from possible adhesions. Synovial folds, which may be large, are usually observed medially and laterally; an anterior fold is less common. The anterior synovial fold is adherent to the neck and only recognizable by its single fibers covering the bone of the neck. The lateral fold indicates the site of entry of the perforating arterioles, which are important for vascularization of the femoral head [19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree