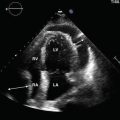

Fig. 7.1

Left—Curvilinear probe with orientation marker out of field of view. Right—Curvilinear probe with the orientation marker on the lateral side

Fig. 7.2

Left—For the transverse plane, the marker is pointed toward the mannequin’s right side. Right—Transabdominal image of the uterus (U) in the transverse (axial) plane. The bladder (star) creates an anterior acoustic window

During ultrasound examinations, the gravid uterus may compress the maternal inferior vena cava, causing maternal flushing, nausea, anxiety, and discomfort. These manifestations of maternal vascular obstruction are part of the supine hypotensive syndrome . Placing the patient in the upright or left lateral decubitus position usually provides immediate relief [11].

Probe Selection and Scanning Techniques

Sonographic evaluation of the pelvis can be performed either transabdominally using the curvilinear array or transvaginally using the endocavitary transducer.

Transabdominal Sonography Using the Curvilinear Probe

The transabdominal approach allows evaluation of various pelvic and intra-abdominal structures, including the hepatorenal space (Morison pouch) and gallbladder [12]. The transabdominal view has two planes: sagittal and axial (Fig. 7.3). Often the sagittal view is described as longitudinal. The axial plane may be described as transverse. To begin, hold the probe in the right hand with the thumb touching the probe’s orientation marker (often a ridge). The marker should correspond to a dot on the upper left portion of the screen. Images at the top of the screen are closer to the probe. Images at the bottom of the screen are farther away from the probe.

Fig. 7.3

Left—The Curvilinear probe positioned for the axial view. Right—The probe is rotated to produce the sagittal view

Transvaginal Sonography with the Endocavitary Probe

During a transvaginal ultrasound, the endocavitary probe (EC) operates at depths between 5 and 10 cm. The anatomy is visualized in two planes: the longitudinal (sagittal) (Fig. 7.4) and the coronal (transverse or axial) (Fig. 7.5). Before starting the examination, ask the patient to empty their bladder to make the exam more comfortable for the patient and to improve visualization. The operator places conductance gel on the probe tip and covers the transducer with a sheath or condom. The sonographer then places lubricant on the outside of the cover. After informing the patient, the EC probe is inserted and the exam begins with the marker at the 12 o’clock position.

Fig. 7.4

Left—An endocavitary transducer introduced into a mannequin. Note the probe’s marker pointing toward the 12 o’clock position, generating a sagittal image. Right—Contrast the semicircular representation of the endocavitary probe to the arch of the curvilinear probe. The bladder (star) and cervix (C) are represented on the screen

Fig. 7.5

Left—While inside the mannequin, the probe is rotated 90° counterclockwise to generate the coronal view. Note the marker pointing toward the 9 o’clock position. Right—The resultant coronal image of the uterus, gestational sac, fallopian tubes, and ovaries

The Longitudinal Plane

By convention, the longitudinal view is the first plane obtained when performing TVS. When the probe marker points toward the ceiling, the sagittal plane is displayed on the screen with clear visualization of the long axis of the uterine body and endometrial stripe. The cervix is on the screen’s right side, and the bladder is on the screen’s upper left portion (Fig. 7.6). Difficulty obtaining this standard view can signify anatomical variation or erroneous machine settings.

Fig. 7.6

A retroverted uterus with calipers measuring the endometrial stripe. The cervix is located on the screen’s right, and the fundus is on the left. Note the more balanced gain setting in this view

The Coronal Plane

To obtain a coronal view of the uterus, rotate the EC probe counterclockwise 90° moving the marker from the 12 o’clock to the 9 o’clock position (Fig. 7.7). The image plane is now perpendicular to the uterine body and divides the patient into cephalic and caudal regions.

Fig. 7.7

Coronal probe position obtained after rotating the probe counterclockwise by 90°. The probe’s marker is no longer visible and points toward the patient’s right thigh

The screen’s left and right sides should represent the patient’s right and left, respectively. The transvaginal probe is moved vertically or horizontally or may also be rotated. These maneuvers can be disorienting but gather essential information for diagnosis. The sonographer maintains orientation by limiting the probe’s rotation to the 90° between 9 and 12 o’clock.

To systematize the description and performance of bedside TVS, we divide the pelvis into nine sectors to be evaluated in both the longitudinal and coronal planes (Fig. 7.8).

Fig. 7.8

Descriptive map of the endocavitary probe position. Rotate the probe counterclockwise by 90° to obtain a coronal view

The Nonobstetrical Sonographic Examination

The Cervix

The cervix is the lower portion of the uterus that communicates with the vagina through the endocervical canal. Like the uterus, the cervix is a vascular, hormonally responsive tissue with glandular components. These endocervical glands can become obstructed (Nabothian Cysts) (Fig. 7.9), especially during ovulation. The cervical length (CL) should be measured transvaginally in the sagittal plane using a straight line to connect the internal and external os, the [13]. The CL reliably predicts the likelihood of preterm birth [14, 15]. It is usually greater than 30 mm. When it measures less than 25 mm prior to 24 weeks gestation, the cervix is considered shortened [14, 16, 17].

Fig. 7.9

Nabothian cysts (arrows) are obstructed endocervical glands. The cystic fluid is a vascular and anechoic with a surrounding thin, hyperechoic wall. Note the adjacent gestational sac (star) with the placenta covering the internal cervical os

Describe the length and morphology of the cervix.

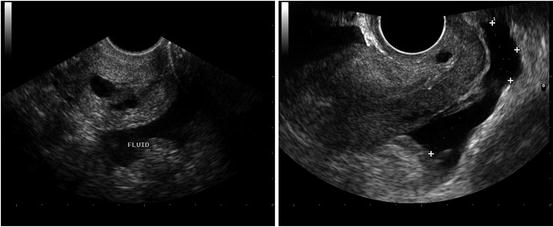

Evaluate the posterior cul-de-sac (Pouch of Douglas) for free fluid (Fig. 7.10).

Fig. 7.10

Left—complex fluid with clots and debris in the Pouch of Douglas. A hemorrhagic corpus luteal cyst ruptured during the first trimester. Right—Transvaginal sagittal image with simple, gravity dependent free fluid in Pouch of Douglas

The Uterus

The average nongravid uterus measures 7 cm long and 3–4 cm in width and height [18]. The uterine volume increases after each pregnancy. Roughly the size and shape of a pear, the nulliparous uterus is composed of three layers: the covering serosa , the muscular hypoechoic myometrium , and the dynamic hyperechoic endometrium that lines the intrauterine cavity [19].

The relationship between the uterine body and cervix determines uterine position. To describe this relationship, the sonographer relates the long axis of the uterus to the vaginal canal (version) and cervix (flexion).

Note if the uterine position is anteverted or retroverted.

With anteversion , the fundus points anteriorly toward the bladder (Fig. 7.11).

Fig. 7.11

Sagittal view of free fluid surrounding the uterus. Note the Pouch of Douglas, the triangular bladder (arrow), and solitary nabothian cyst

With retroversion , the fundus points posteriorly away from the bladder (Fig. 7.12).

Fig. 7.12

Sagittal image of retroverted, retroflexed uterus with endometrial stripe measurement (calipers). The fundus opposes the bladder and nabothian cysts are noted

With anteflexion , the anterior aspect of the bladder is concave (Fig. 7.13).

Fig. 7.13

Transvaginal image demonstrating an anteverted, anteflexed uterus in the sagittal plane. Notice the high gain function counfounding interpretation by decreasing the contrast resolution

With retroflexion , the bladder wall is convex (Fig. 7.14).

Fig. 7.14

Sagittal image of an anteverted and retroflexed uterus. Calipers are measuring the length of the uterus. Note the convex appearance of uterus

Measure the uterine length from the fundus to the cervix in the sagittal plane.

Measure the uterine height (depth) perpendicularly to the length using an anteroposterior measurement in the same longitudinal plane.

The uterine width is the largest measurement obtainable in the coronal view.

Measure the endometrial thickness or stripe.

The Fallopian Tube (Salpinx)

The fallopian tubes cannot be visualized in the absence of pathology or iatrogenesis. Near the patient’s midline, the uterus surrounds the interstitial portion of the salpinx. The extrauterine isthmus widens into the infundibulum and fimbria, which opens directly into the peritoneum. A visible, fluid-filled hydrosalpinx suggests previous tubal surgery or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). A hydrosalpinx may appear cystic with incomplete septations and endosalpingeal folds that look like “beads on a string.” The dilated fallopian tube should be differentiated from the adjacent ovary to ensure a correct diagnosis [20].

The Ovaries

Like the uterus, the ovary is a hormonally responsive organ that changes appearance with the menstrual cycle. The ovaries are measured in three perpendicular orthogonal planes. The transvaginal longitudinal plane best measures the length and height (anterior–posterior diameter); the transvaginal coronal view best measures the width. Premenopausal, nondominant ovaries measure approximately 2 cm × 2 cm × 2 cm [21]. A normal, nondominant ovarian volume measures less than 10 cc.

Ovarian volume decreases with age and oral contraceptive use [21]. Initially, each ovary contains several follicles that measure less than 1 cm in diameter. After 7 days, a single ovarian follicle emerges and will grow to a diameter slightly greater than 2 cm. This dominant follicle will then rupture and become the vascular corpus luteum, which on sonography has a crenulated appearance and thickened wall [22].

Locate the cornua and attempt to visualize the salpinx.

Normal fallopian tubes are difficult to identify.

Sweep out from the axial plane of the uterine fundus and locate the iliac vessels and identify the ovaries (Fig. 7.15).

Fig. 7.15

Right (intraperitoneal) ovary with adjacent, (retroperitoneal) iliac vasculature (star). The ovarian fossa abuts the hypgastric artery and vein

Measure the ovarian height, width, and length using two orthogonal planes.

Describe the ovarian morphology.

Common Nonobstetrical POCUS Findings

Simple Ovarian Cysts

On transvaginal ultrasound, 2 % of pregnant women and 10 % of all women will have a functional ovarian cyst or cysts [23, 24]. Follicles generally have a diameter less than 2–2.5 cm, and a cyst’s diameter usually exceeds 2.5 cm. For simple cysts in premenopausal women, repeat ultrasound at 6-week intervals so the images will correspond with a new cycle at a different phase than the previous examination. If a cyst is unilocular and has a diameter less than 10 cm, the malignant potential is less than 0.1 % [20, 25].

Corpus Luteum Cysts

The corpus luteum forms in the potential space left by a ruptured, dominant follicle. Corpus luteum cysts are the most common ovarian masses during early pregnancy. These cysts can hemorrhage, torse, or rupture. Under these circumstances, patients present with acute abdominal pain. In pregnancy, corpus luteum cysts (Fig. 7.16) may persist for 16 weeks and exceed 10 cm in diameter [26–28].

Fig. 7.16

Beta-hCG stimulated the corpus luteum (star) to produce progesterone. A corpus luteum cyst is an example of a functional cyst and has a thickened wall. It is not uncommon to see echogenic hemorrhagic material within the cysts

Hemorrhagic Cysts

With a rich vascular supply, the cystic morphology of the hemorrhagic corpus luteum has a varied appearance that is related to the formation and absorption of blood clots. On ultrasound, hemorrhage can have a reticular, cobweb appearance within a complex cyst. In general, cystic hemorrhage should resolve within 2 months [20].

For premenopausal women:

Hemorrhagic cysts measuring less than 3 cm do not require description or repeat testing.

Hemorrhagic cysts between 3 and 5 cm merit description but not repeat testing.

Hemorrhagic cysts greater than 5 cm in diameter merit description and repeat testing in 6–12 weeks, at the beginning of a subsequent menstrual cycle.

A hemorrhagic cyst in a postmenopausal woman is considered malignant until proven otherwise.

Pelvic Pain

Pelvic pain can be classified as either acute or chronic and is related to menses and pregnancy. The investigation of pelvic pain drives almost half of gynecological diagnostic laparoscopies [29]. In general, non-cyclic chronic pelvic pain must persist for at least 3 months irrespective of menses. Cyclic chronic pelvic pain changes with relation to the menstrual cycle and persists for at least 6 months [26]. Common causes of both cyclic and non-cyclic chronic pelvic pain include endometriosis, adenomyosis, postoperative adhesions, and fibroids. For this chapter, our focus is on acute pelvic pain related to the adnexa and uterus in the nonpregnant patient [30].

Adnexal Torsion

Adnexal torsion is a sudden disruption of adnexal arterial blood flow. Patients with ovarian torsion experience acute abdominal pain. Risk factors include preexisting adnexal enlargement, often secondary to an occult teratoma or ovarian cyst. Use the following facts to aid rapid diagnosis and intervention: [26, 29, 31].

The torsed ovary appears grossly enlarged, often five times larger than average.

The presence of arterial or venous blood flow does not reliably exclude torsion.

20 % of cases present during pregnancy.

Teratomas and ovarian cysts are frequent causes of acute torsion.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID)

PID includes endometritis, salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscesses, and pelvic peritonitis. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) , specify in their diagnostic criteria for PID that the patient must have uterine, adnexal, or cervical motion tenderness [30, 32]. In the USA, PID is diagnosed over one million times annually. The incidence of chlamydia has quadrupled over the last 25 years, with particularly high rates in urban environments. In some neighborhoods, more than 25 % of young women test positive for chlamydia [33].

Without treatment, many women with PID will partially resolve the initial painful symptoms but will become infertile secondary to chronic inflammation. For diagnosing PID, pelvic ultrasound has a high sensitivity and specificity and may simultaneously exclude other obstetrical and gynecological causes. A dilated, fluid-filled hydrosalpinx is present in most cases of PID . Cine-looping can help differentiate a folded, dilated tube from a septated cyst. Color Doppler can distinguish an iliac vein or anomalous varix from a dilated fallopian tube.

Acute Salpingitis and Tubo-ovarian Abscess (TOA)

Salpingitis is inflammation of the fallopian tube that can progress to an abscess (Fig. 7.17). Tubal inflammation and its sequelae fall within the broader categories of acute or chronic PID. Sonography has improved the clinician’s ability to accurately diagnose pelvic infectious disease: [3, 26, 34]

Fig. 7.17

Left ovary with adjacent hydrosalpinx. Note the tortuous, serpiginous appearance of the affected tube (arrow). The incomplete septations of a hydrosalpinx can be mistaken for a complex ovarian cyst

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree