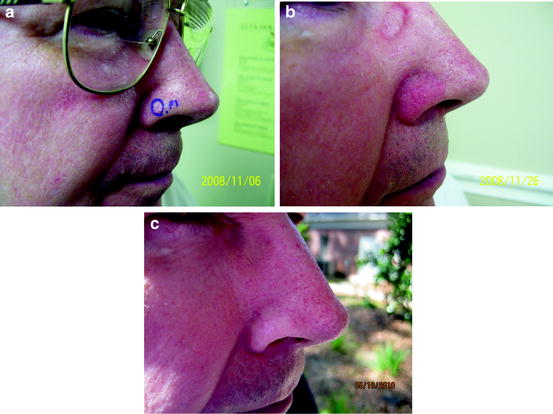

Fig. 1

Patient with nodular basal cell carcinoma of right ala before (a), 3 years after (b), and 6 years after (c) superficial radiation therapy

Fig. 2

A patient with a nodular BCC of the right ala before (a), during (final treatment) (b), and 350 days after radiation therapy (c)

Fig. 3

Patient with SCC in situ of the forehead on day of first treatment. The inner marked circle represents the clinical lesion while the outer circle represents a 10 mm clinical margin (a), the day of final treatment (b), 14 days after with normal desquamation (c), 37 days after (d), 44 days after (e), and 106 days after radiation treatment (f)

Fig. 4

A patient with biopsy proven SCC in situ of the left cheek prior to (a) and 4 years after radiation therapy (b)

The initial scarring with resulting hypopigmentation, permanent alopecia, and telangiectasias which typically arise within treatment sites over the decades should be discussed and compared to the scarring, pain, and potential disfigurement of surgical excision and repair. One should discuss with the patient improved cosmesis with increased fractionation (and increased cost) and how scars from surgery generally improve with time compared to the skin changes from radiotherapy. As discussed in greater detail in Chap. 9, logistical variables such as age of the patient, medical comorbidities, transportation, and cosmetic concerns all go into the decision process when choosing treatment regimens and fractionation schemes.

In contrast to surgery, the initial scarring from radiation therapy is minimal the first 1 or 2 years after radiation. It starts out gradually with hypopigmentation, followed by atrophy, and eventually telangiectasia occurs many years later. These lesions are discoid in appearance and can become very prominent over time. As discussed, the thick rhinophymatous skin of the nose holds up better to radiation than the thin skin of the cheek or forehead. In this location, short and long-term scars are often far superior than surgery and complex closure. Scarring from radiation is dependent on fractionation. If scarring is a prime factor or concern for the patient, one can utilize 10, 15, or even 20 fractions to minimize this.

Comparison to Electron Beam Radiotherapy

Photon SXRT differs from electron beam radiotherapy in that light is the energy source rather than a charged particle. The machines are smaller and less expensive as a linear accelerator is not required, and the applied physics and dosimetry are inherently simpler. With SXRT, a complex physics calculation and bolus are not needed in order to deliver 100 % of the dose to the skin surface as is required with electron beam therapy. Additionally, the beam and delivered dose with SXRT have far less lateral edge beam drop-off in the umbra of the treatment site [21, 22]. Technical factors such as these may have contributed to the inferior cure rates of electron beam therapy reported in the literature [21]. Lastly, SXRT is more cost-effective in terms of equipment and patient costs. Electron beam therapy, however, can be used to treat broader areas of the skin than can typically be utilized with SXRT and by virtue of its long TSD, may be superior in delivering a homogenous dose in complex topographical treatment sites (i.e., Perforating lesions of the nares). Electron beam therapy also has an established role in adjunctive therapy in tumors with perineural invasion, in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and in select melanomas of the head and neck [18, 23, 24].

It is our standard practice to review the histological slides of all patients that are referred to us for Mohs surgery and at the same time review their medical history, age, and location of tumors. Each tumor is looked at histologically to ascertain tumor depth and to identify aggressive features or lack thereof. On the appointed day of surgery, patients are given during informed consent the option for Mohs surgery and repair. In patients over age 65 where the tumor is nonaggressive and we can delineate it well, we will offer them superficial X-ray for tumors on the head and face. In cases of aggressive tumors in patients whom we do not think are good surgical candidates, we typically refer them to our local radiation oncologist or our regional colleagues. If the tumor is highly aggressive, we typically refer the patient to a tertiary care referral center tumor board. We work closely with our radiation oncologist colleagues for patients who have aggressive squamous cells and require postoperative radiation for perineural invasion or other factors.

We have seen and reported multiple SCC in situs and other tumors (e.g., atypical fibroxanthomas) arising in the radiation field for scalp lesions treated with electron beam for perineural invasion and attribute it to the widened 80–20 % penumbra that occurs on convex surfaces resulting in a paradoxical subtherapeutic carcinogenic dose to the periphery of the treatment field [25]. Nevertheless, it remains in invaluable tool in adjunctive therapy for aggressive tumors with perineural invasion.