and Alfredo Blandino1

(1)

Department of Radiological Sciences, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

The potential of MREg/MREc to evaluate Crohn’s disease patients has been investigated extensively in the previous chapters. Nowadays, technological developments have extended the role of MRI in the evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract.

In fact, both these techniques are assuming an interesting role also in the detection of other small bowel diseases, including tumors [1, 2].

Moreover, the gastrointestinal radiologist should take into account that an increasingly large spectrum of bowel and mesenteric diseases can be incidentally diagnosed by performing MR of the small bowel.

An example can be seen in patients with suspicion of gastrointestinal tract congenital rotation and fixation anomalies. In such cases, symptoms are not caused by the abnormal position of the bowel, but they are due to complications that occur when an abnormal position or fixation of the mesentery may cause volvulus. Symptoms can vary from mild (e.g., nonspecific complaints that could lead to the incorrect diagnosis of gastric ulcerations or irritable bowel syndrome) to acute (i.e., midgut volvulus), rare in adults [3, 4]. Some highly suggestive signs of midgut rotation and fixation anomalies are the position on the right-hand side of the abdomen of the duodenojejunal junction (ligament of Treitz) and proximal loops of the jejunum, as well as the lack of the normal midline position of the horizontal part of the duodenum. A rotation of the superior mesenteric and adjacent mesenteric fat around the superior mesenteric artery (whirl sign), even if not specific to midgut volvulus, can also be related [5].

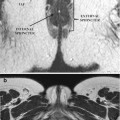

A primarily pediatric condition, rarely seen in adults, is intussusception, defined as the invagination of a bowel loop with its mesenteric fat into the lumen of the adjacent bowel [6]. The use of a cross-sectional imaging technique as MR of the small bowel frequently allows the recognition of this condition, which presents with a pathognomonic target-like (bowel-into-bowel) mass, due to the telescoping of the bowel and its trapped mesenteric fat and vessels into an adjacent bowel tract [6–8], a condition that may finally cause bowel obstruction.

Sometimes, protrusion of the viscera within the peritoneal cavity through a normal or abnormal peritoneal or mesenteric opening (congenital or acquired) can be seen during MR of the small bowel, allowing the diagnosis of internal hernias. Clinical manifestations may be not specific, with only mild abdominal complaints if the hernia is reducible. Naturally, in case of incarcerated hernia, acute small bowel obstruction is very frequent [9–11]. There can be different types of internal hernias (paraduodenal, pericecal, transmesenteric, intersigmoid, paravesical, and Winslow’s foramen hernias), and they all can be seen by performing a MREg/MREc [9–12].

A congenital anomaly most common in the gastrointestinal tract and particularly in patients affected by Crohn’s disease is Meckel’s diverticulum [13]. It is the result of incomplete atrophy of the omphalomesenteric duct, and it has to be considered as a true diverticulum on the antimesenteric side of the distal ileum containing three layers of the bowel wall. Ectopic gastric or pancreatic mucosa is present in 50 % of all Meckel’s diverticula; in fact, the most frequent complication is represented by peptic ulceration and bleeding from heterotopic mucosa [13, 14]. On MREg/MREc, Meckel’s diverticulum is diagnosed when a saccular, blind-ended structure continuous with the ileum is identified; when inflamed, it usually has a distended lumen and surrounding inflammatory infiltration.

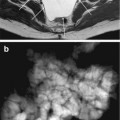

Multiple polypoid lesions in the gastrointestinal tract may be detected on high-resolution MR imaging of the small bowel in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Polyps may vary in location, appearance (sessile or pedunculated), and size (from small to large) and tend to enhance after injection of gadolinium, helping to differentiate them from bowel content. MREg/MREc may be performed to detect and monitor polyps of the gastrointestinal tract (polyps larger than 1.5–2 cm are considered potentially malignant and should be removed) and in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, in the suspicion of intussusception. Although multiple polyps of the gastrointestinal tract are typical of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, they are not specific and may be found also in other syndromes such as juvenile polyposis, familial adenomatous polyposis, and Cronkhite–Canada syndrome [15]. Naturally, the diagnosis must be based not only on radiological findings but also on clinical and histopathology results [16].

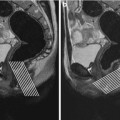

For what concerns the neoplastic disease, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are mesenchymal neoplasms affecting the gastrointestinal tract, with the highest prevalence in the stomach (70 %). In rare cases, they may be found in the omentum, mesentery, or retroperitoneum. The clinical presentation is variable, also depending on the involvement of adjacent organs, metastases, or peritoneal seeding.

They usually appear as well-circumscribed, heterogeneous, and exophytically growing masses with peripheral contrast enhancement. The degree of signal intensity on MRI and its homogeneity depend on tumor necrosis and hemorrhage. Solid parts of the tumor may appear hyperintense on T2-weighted images and enhance after intravenous injection of gadolinium [17–19].

Lymphoma is considered to account for 20 % of all primary small bowel malignancies.

The terminal ileum is considered to be the most frequently affected site in the small bowel, as there is a relative abundance of lymphoid tissue, and patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease are associated with a small but measurable increased risk of lymphoma due to medications, disease activity, and underlying disease-related immune alterations [20].

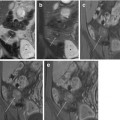

Infiltrative and polypoid forms are the two main growth patterns of primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. Infiltration is usually circumferential, homogeneous, and over a different length. Multifocal involvement of the small bowel is possible and is thought to be more common in primary T-cell lymphoma [21]. Preservation of the surrounding fat tissue and a long involved segment helps to differentiate lymphoma from adenocarcinoma, even if a high-grade lymphoma may infiltrate the mesenteric fat. Lymphoma may also ulcerate, perforate, or create fistulas into the adjacent mesenteric or adjacent bowel loops, which makes it hard to distinguish from Crohn’s disease on MREg/MREc [21–23].

Adenocarcinoma is a malignant neoplasm of the glandular epithelium. Despite its low incidence (<1 % of all primary malignancies), it is the most common primary malignant tumor of the small bowel and usually occurs in the proximal intestine, duodenum, and jejunum. It often metastasizes to regional lymph nodes, liver, or peritoneum [24–26]. At MREg/MREc, it may appear as an infiltrative lesion that causes luminal stenosis and obstruction, with pre-stenotic dilatation or as polypoid intraluminal masses, less common. MR fluoroscopy shows circumferential and sharply demarcated narrowing of the lumen, with shouldering of the margins due to mucosal destruction. A moderate and heterogeneous enhancement is typically demonstrable on post-gadolinium images. Usually, adenocarcinomas tend to infiltrate the entire bowel wall and extend into the surrounding mesenteric fat tissue, causing a desmoplastic reaction, which is easily assessed at MRI. Other typical features of adenocarcinomas include the proximal location, the solitary presentation, and the involvement of short segments of bowel with infiltration of perivisceral fat [27].

Carcinoids are well-differentiated endocrine tumors arising from the enterochromografin cells at the base of the Lieberkühn’s crypts and account for nearly 25 % of primary malignant neoplasms of the small bowel [26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree