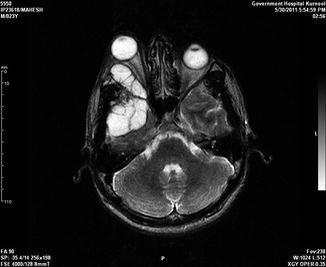

Fig. 19.1

Enormous numbers of cysts of different sizes in a case of cranial hydatid disease in frontal region involving orbit with spread into the intracranial epidural space. Recurrence of the lesion occurred 1 year later in spite of prolonged chemotherapy

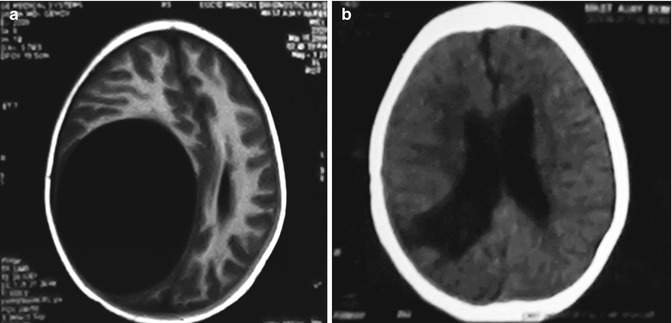

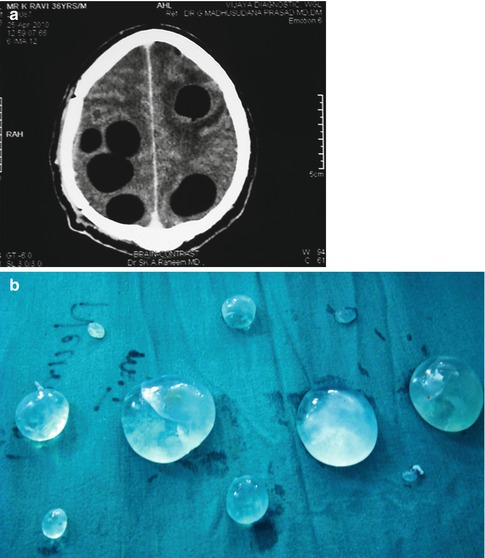

Fig. 19.2

(a, b) Single primary cystic lesions of the type depicted above, even if large reaching on to the surface in accessible areas are amenable for complete excision with a cure. Preop scan on the left and post-op scan on the right side

Fig. 19.3

(a, b) The best surgical outcomes are recorded also in cases of hydatid disease of the central nervous system when the lesion is primary solitary and even if it is located in deeper areas of the brain as shown above. This kind of lesion needs planning and requires microsurgical methods for excision without spillage. Same is true for rare primary spinal epidural and intradural and extramedullary lesions. Scans shown in this figure belong to a 24-year-old lady from an endemic area of hydatid disease. Picture on the left is before surgery, and the scan on the right side is after the total excision of solitary primary lesion. Microscopic excision is helpful in these cases which provide good illumination and careful dissection. Adults seek treatment earlier, and the lesions tend to be smaller in size as compared to those of children where the cysts grow to a large size and their excision without breaking of the cyst may sometimes be difficult due its sheer size with thin walls especially towards the ventricle

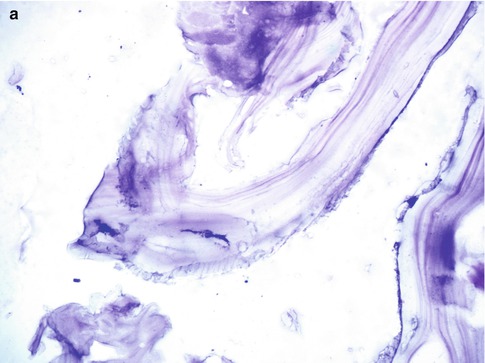

Fig. 19.4

(a, b) Laminated membrane of the hydatid cyst wall with an inner germinal layer. Hematoxylin and eosin magnification 110× on left (a) and 200× (b) on the right side, respectively

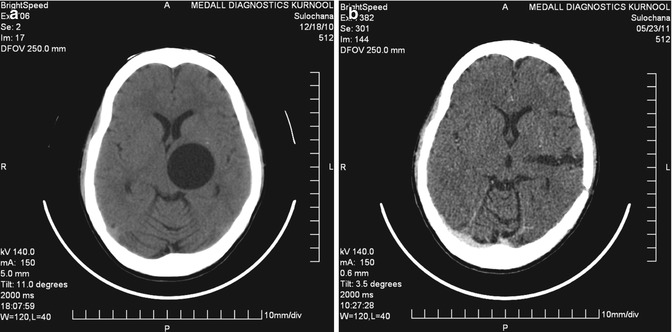

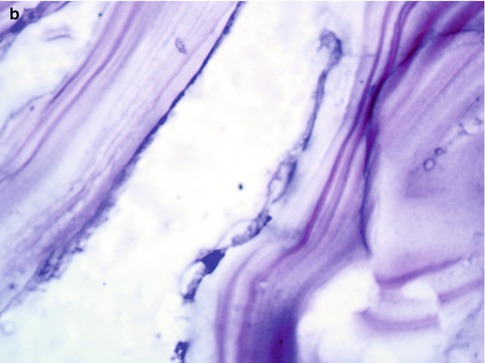

Fig. 19.5

A 40-year-old male with right parieto-occipital primary multiple hydatid cysts in close proximity

Sometimes successful excision of the alveolar lesions which are in an accessible location followed by a piecemeal of those in difficult locations resulted in good neurological recovery (Wang et al. 2009). Alveolar type of hydatid disease may sometimes mimic a brain tumor, and its total excision may be difficult (Senturk et al. 2006; Ma et al. 2009). Rarely granulosus lesions could be multiple and may be present in different hemispheres, and such cases need planned excision in one or more stages (Yuceer et al. 1998). Liver and lung disease may be responsible for delayed deaths later on in spite of chemotherapy. In a Chinese study, two of the six surgically treated cases of cerebral hydatid disease of the alveolar type died due to end-stage liver disease (Wang et al. 2009). In a recent study, injection of 0.04 % chlorhexidine into the cysts (hepatic) for 5 min had been shown to kill all the live scolices and there was no recurrence over a follow-up period of 2 years (Topcu et al. 2009). However, this method is yet to be tried in cerebral and cranial hydatid disease. One has to study the deleterious effects of 0.04 % chlorhexidine to the brain, if that were to get spilled over accidentally during the operation. Effective scolicidal agent is useful especially while removing the cysts containing fertile scolices. Viability and fertility of the protoscolices and viable germinal layer determine the recurrence of the disease at a later date (Manterola et al. 2006). Orbital location of hydatid disease is a rare type of infestation, and total extirpation of the cysts without rupture may be difficult, and in such cases recurrence is the result (Fig. 19.6; Ghosh et al. 2008). Endoscopic approaches are available in the management of orbital hydatid disease. Cranial and vertebral hydatid disease invariably recurs because of spillage of large numbers of daughter cysts. Long-term chemotherapy preferably a combination of albendazole and praziquantel is recommended in such cases. Recurrence of spinal disease even with chemotherapy may benefit from reoperative surgery since the recurrent cysts may be without a brood capsule and hence they may not recur again. Intact excision was possible in 119 cases out of 137 cases of cerebral hydatid disease (Turgut 2002). In 22 % of cases, recurrence was noted and surprisingly recurrence occurred in 7 of the cases which were removed intact. Recurrence was expected in such of those cases which ruptured during surgery, and these were 7 out of 31 (Turgut 2002). Recurrence in those cases depends upon the presence of live protoscolices, and these can be estimated per field, and it is also known that fertile cysts contain malate fumarate along with other resonances. Greatest number of viable protoscolices was observed in multiple cysts in comparison to single cysts (Manterola et al. 2006). Preoperative studies will help in planning the surgery as well as the precautions that should be taken to avoid risks of surgery. Microscopic surgery gives good illumination and helps in proper dissection of the cysts. Cyst rupture during surgery is always critical, and the recurrence depends upon whether the lesion is primary or secondary. In one study with long-term follow-up, out of 29 cases operated, 18 were removed intact and 8 cases ruptured, of which 5 are dead (63 %) and they were all primary. In contrast 3 cases also ruptured and they were secondary and they are alive proving that secondary lesions are not fertile. Recurrence after rupture is a problem, and even if there are many lesions, they should be removed and the results can be gratifying (Fig. 19.7). The complications of cerebral hydatid cyst surgery are not uncommon which require prompt diagnosis and treatment (Tuzun et al. 2010). Subdural effusion and porencephaly are the delayed complications, whereas hemorrhage in the operated site and extradural hematomas are immediate problems. Rarely there could be infected hydatid cysts which need antibiotic coverage (Obrador and Urquiza 1948; Arana-Iniguez and Julian 1954).

Fig. 19.6

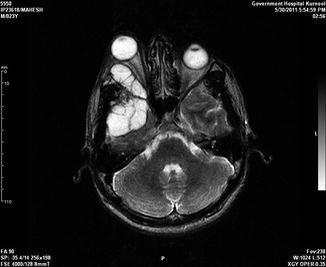

A 23-year-old male with recurrent hydatid cysts involving the orbit, frontal, and temporal regions

Fig. 19.7

(a, b) A 34-year-old male with recurrence after rupture during first operation. There were six large lesions and a few smaller lesions which were all removed with good outcome

Medical Treatment

Medical treatment may be chosen if patients are not eligible for surgery or the cysts are present in many organs. Albendazole, mebendazole, and praziquantel are the main drugs used as antiparasitic medication for the treatment of echinococcal infection (Davis et al. 1989; Gil-Grande et al. 1993). Albendazole is a broad-spectrum benzimidazole which is preferred over mebendazole because it is better absorbed and achieves higher blood, cyst wall, and fluid concentrations. Both act by inhibition of tubulin polymerization resulting in the loss of cytoplasmic microtubule formation inhibition and the inhibition of the glucose uptake of the parasites leading to cell autolysis (Silva et al. 2004; Kappagoda et al. 2011). Albendazole sulfoxide, the active metabolite, reaches predictable levels in serum after an oral dose; cyst fluid levels are slowly reaching therapeutic levels and are less predictable; thus a prolonged duration of treatment is required. It is effective against the larval forms of echinococcal infection. Albendazole results in disappearance of up to 48 % of cysts and a substantial reduction in size of the cysts in another 28 %. It is another drug for the treatment of hydatid disease, but it does not produce adequate serum levels which are able to kill the germinal membrane alone and can be used along with albendazole. It increases serum concentrations of albendazole to the fourfold and can be used in combination, which is advisable (Sihota and Sharma 2000; Jamshidi et al. 2008). The duration of anthelmintic treatment could be up to 5 months or longer. Anthelmintic therapy is beneficial and indicated in patients with spillage or in those patients with disease in other parts of the body, like the liver and lungs. Severe disease in organs other than the CNS may be responsible for delayed deaths. The response to albendazole treatment for cerebral hydatid disease can be monitored with CT and MRI imaging (Kalaitzoglou et al. 1998). There are reports that a viable residual spinal hydatid cyst disappeared with albendazole therapy (Baykaner et al. 2000). Preoperative combination chemotherapy is more effective for post-spillage prophylaxis than albendazole or praziquantel alone (Morris 1987). There are also reports claiming that albendazole is not effective in the treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts (Kapan et al. 2008).

Hydatid Disease in Other Parts of the Body

Presence of hydatid lesions in other parts of the body also determines the outcome of treatment (Fig. 19.8). In a recent study, six cases of intracranial hydatid cysts were operated, but two of these subsequently died from severe forms of liver involvement sometime later (Wang et al. 2009). These cases had no recurrence of cerebral lesions even though they were removed piecemeal. Liver transplantation is now possible in cases with hepatic hydatid disease. Same may also happen in the cases with involvement in other parts of the body such as the lungs. Turgut (1997) reviewed the hydatid disease of the spine in Turkey and reported that 14 out of 18 cases of hydatid disease had pulmonary involvement. Naturally, disease in other parts of the body dictates the outcome of hydatid involving the CNS.

Fig. 19.8

Central nervous system hydatid disease with involvement of liver that determines the ultimate outcome of the patient. Echinococcosis of the alveolaris type invariably has the liver involvement, and their survival depends upon the liver status

Delayed Complications

Sometimes hydatid cyst could be associated with other primary lesions of the brain such as acoustic neurinoma and glioma. Prognosis depends upon the other associated disease (Cohen et al. 1997). Delayed development of glioma at the same site of previous hydatid cyst raises the doubt whether constant irritation may be responsible for its development (George et al. 2003). But glioma development in this case could have been incidental also.

Outcome and Prognosis of Hydatid Disease Involving the Central Nervous System

Hydatid disease causes considerable mortality and morbidity, and a large population around the world is affected by the disease (McManus et al. 2003). Surgical removal of the clinically symptomatic primary cysts is curative, and treatment with anthelmintics in nonoperable cases is only palliative. Long-term experience of the treatment of alveolar types of hydatid disease is not rewarding (Pau et al. 1987; Reuter et al. 2001; Buttenschoen and Buttenschoen 2003; Buttenschoen et al. 2009). Forty-two percent of cases were cured, and in the remaining 58 %, palliative treatment alone was possible.

The Australian Hydatid Registry contained 1,802 cases by the end of 31 March in 1945, and only 16 of the cases showed a brain involvement. The registry estimated the deaths from hydatid disease as 16.6 %, but they cautioned that this number was fallacious since this was the number of patients with hydatid disease who died in hospitals (Barnett 1936). In a survey the number of hydatid deaths till then were given as 276, but the actual number of dead was 534 because more deaths occurred in the homes of the diseased. Probably the best strategy of any public health policy should be prevention and control of the hydatid disease. Each country needs to find the echinococcal species causing the disease and the definitive and intermediate hosts responsible in the life cycle of the parasite (Palmer et al. 1996). In some countries both forms of the disease, E. granulosus and E. alveolaris, may be prevalent. For India the definitive host is the domestic dog and the intermediate hosts are sheep, goat, and cattle. In a study on the incidence of hydatid infestation in intermediate hosts in Kurnool of Andhra Pradesh, India infection rates of goats, sheep, and cattle were 16.96, 21.75, and 60.94 %, respectively. 33.3 % of dogs were positive in Kurnool region (Reddy et al. 1968; Reddy and Murthy 1986). These facts emphasize the importance to control the disease in intermediate hosts and definitive hosts to contain the hydatid disease (Reddy 2009).

Conclusion

Long-term outcome of cerebral hydatidosis can be summarized as follows: (1) Surgical treatment remains the preferred management of active hydatid disease involving the brain; (2) the best surgical outcomes are recorded in cases of cystic hydatid disease where the lesion is primary solitary and is located in an accessible area which can be excised without rupture; (3) the excision of alveolar type of echinococcosis is only palliative in nature; and (4) the presence of hydatid disease in other parts of the body besides the brain determines the long-term outcome of cerebral echinococcosis.

References

Abdel Razek AA, El-Shamam O, Abdel Wahab N. Magnetic resonance appearance of cerebral cystic echinococcosis. World Health Organization (WHO) classification. Acta Radiol. 2009;5:549–54.CrossRef

Al Zain TJ, Al-Witry SH, Khalili HM, Aboud SH, Al Zain Jr FT. Multiple intracranial hydatidosis. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2002;144:1179–85.CrossRef

Arana-iniguez R, Julian JS. Hydatid cysts of the brain. J Neurosurg. 1954;3:232–5.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree