(1)

Princess Elizabeth Hospital Le Vauquiedor St. Martin’s Guernsey, Channel Islands, UK

(2)

Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, England UK

Abstract

Most women who present at the breast clinics have benign breast conditions which range from non-specific breast pain to discrete lumps such as fibroadenomas. Benign breast lesions consist of heterogenous conditions which in the majority of women go undetected and are identified incidentally during screening mammography or in the surgical specimens for cancer. Although most women present with benign breast conditions than with cancer, there is more written about breast cancer than benign lesions because this is the most common malignant tumour in women. Nomenclature of benign breast lesions was confusing in the past with the use of terms such as aberrations of normal development and involution (ANDI), which is supposed to encompass both the pathogenesis and the degree of abnormality (Hughes et al. 1987). The terminology used in this book for benign breast disease is based on the classification by the College of American Pathologists (Hutter 1986; Fitzgibbons et al. 1998) which is used by the UK NHS Breast Screening Programme (2005).

Learning Points

Benign breast lesions are more prevalent than breast cancer.

Benign breast lesions are a heterogeneous group of conditions.

Most benign breast lesions are incidental findings in specimens resected for breast cancer that are detected mam-mographically.

Benign breast lesions require triple assessment.

Accurate classification of benign breast lesions is important as to aid risk assessment for breast cancer.

2.1 Background

Most women who present at the breast clinics have benign breast conditions which range from non-specific breast pain to discrete lumps such as fibroadenomas. Benign breast lesions consist of heterogenous conditions which in the majority of women go undetected and are identified incidentally during screening mammography or in the surgical specimens for cancer. Although most women present with benign breast conditions than with cancer, there is more written about breast cancer than benign lesions because this is the most common malignant tumour in women. Nomenclature of benign breast lesions was confusing in the past with the use of terms such as aberrations of normal development and involution (ANDI), which is supposed to encompass both the pathogenesis and the degree of abnormality (Hughes et al. 1987). The terminology used in this book for benign breast disease is based on the classification by the College of American Pathologists (Hutter 1986; Fitzgibbons et al. 1998) which is used by the UK NHS Breast Screening Programme (2005).

2.2 Clinical Presentation of Benign Breast Lesions

The incidence of benign breast disease begins to rise during the second decade of life and peaks in the fourth and fifth decades, which is in contrast to cancer whose incidence increases after menopause (Guray and Sahin 2006). The clinical presentation of benign breast conditions includes pain, lumps and nipple discharge (Santen 2010). Cyclic breast pain occurs during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle in association with the premenstrual syndrome or independently and resolves after onset of menses (Santen 2010). A study of 1,171 healthy American women reported that 11 % experienced moderate to severe cyclic breast pain and 58 % mild discomfort (Ader and Shriver 1997). Breast pain interfered with sexual activity in 48 %, with physical (37 %), social (12 %) and school (8 %) activity.

The proliferation of the duct–lobular units manifests as a breast lump which is detected by the patient or their clinician. Ninety percent of these nodules or lumps in premenopausal women are benign, usually fibroadenomas (Goehring and Morabia 1997). Other lesions which present as lumps include cysts, sclerosing adenosis and multiple intraductal papillomas.

Nipple discharge is a common presenting symptom, and this represents 6.8 % of referrals to the Breast Clinic, and only 5 % of the patients are found to have serious pathology (Santen 2010). Careful history and examination is important to determine the underlying cause of the discharge. It is important to determine whether the discharge is spontaneous or expressive and whether the discharge is from a single duct or multiple ducts (Santen 2010). Nipple discharge can be physiological or pathological. Physiological discharge is usually non-spontaneous (expressible), from multiple ducts, bilateral and non-bloody. In contrast, pathological discharge is typically spontaneous, serous or bloody, unilateral and from a single duct (Santen 2010). Pathological nipple discharge can be caused by duct ectasia, papilloma or cancer. Patients who present with galactorrhoea require assessment of prolactin.

With the widespread use of screening mammography, most benign lesions are detected mammographically which will represent the majority of the lesions discussed in this book. Screening mammography has led to the detection of hitherto previously unknown lesions such as mucocoele-like lesions and columnar cell lesions.

2.3 Investigation of Benign Breast Lesions

As with breast cancer, women who present with clinically benign breast disease require triple assessment, i.e. clinical examination, radiological assessment and pathological evaluation of the lesion by either fine needle aspiration cytology or needle core biopsy. The patient should be managed with multidisciplinary team which includes the breast surgeon, the radiologist, the pathologist and the clinical nurse specialist in breast care.

The type of imaging depends on the symptomatology and age of the patient. Mansel et al. (2009) provide an algorithm for management of these patients: thus, for a milky nipple discharge in a woman under the age of 40 with no lump, exclude mechanical stimulation, drugs and hormones and reassure; women with watery, serosanguineous and bloody discharges will require radiological investigations and, if symptoms persist, may require subareolar resections. In most hospitals in the UK, the patients have cytological evaluation of the nipple discharge. The presence of cells on the smear is classified as C3, i.e. atypical cells probably benign (NHS BSP Publication No. 58 (2005)). If inflammatory cells and macrophages are present in the smears of non-bloody nipple discharge, usually bilateral with a normal imaging, the cytology will be in keeping with duct ectasia.

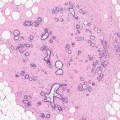

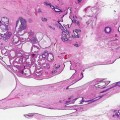

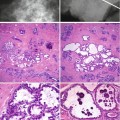

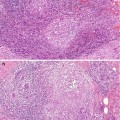

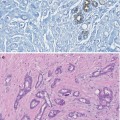

A bloody nipple discharge is not always due to underlying breast lesion e.g., a patient on warfarin for atrial fibrillation presented with unilateral nipple discharge. The radiological investigations were normal. On cytology, the nipple discharge was heavily blood stained and contained haemosiderin-laden macrophages. There were no epithelial cells. As a papillary lesion could not be excluded, the patient underwent subareolar resection. The surgical specimen contained duct ectasia with associated haemorrhage but no papillary lesion (Fig. 2.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree