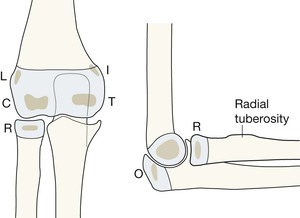

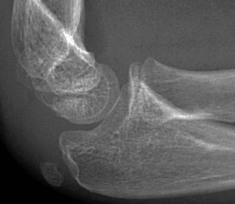

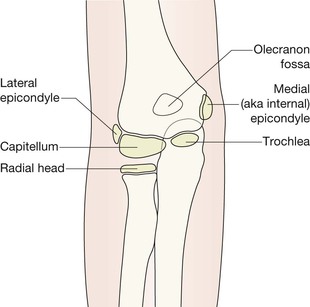

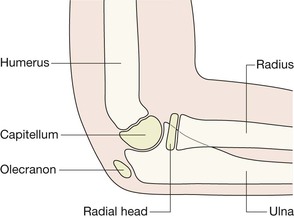

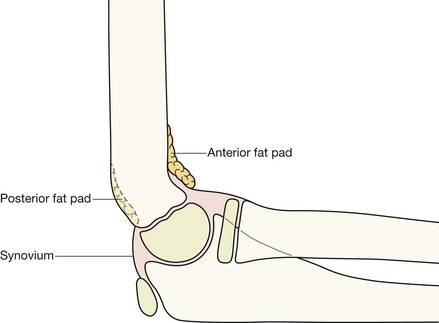

There are pads of fat close to the distal humerus, anteriorly and posteriorly. They are extrasynovial but intracapsular. ▪ Look for the fat pads on the lateral. They are not seen on the AP view. ▪ The fat is visualised as a dark streak amongst the surrounding grey soft tissues. At birth the ends of the radius, ulna and humerus are lumps of cartilage, and not visible on a radiograph. The large, seemingly empty, cartilage filled gap between the distal humerus and the radius and the ulna is normal. From 6 months to 12 years the cartilaginous secondary centres begin to ossify. There are six ossification centres. Four belong to the humerus, one to the radius, and one to the ulna. Gradually the humeral centres ossify, enlarge, and coalesce. Eventually each of the fully ossified epiphyses fuses to the shaft of its particular bone. Exceptions are an occasional normal variant3,4. A 2011 survey4 of 500 paediatric elbow radiographs found: ▪ CRITOL is a really helpful tool when analysing a child’s injured elbow. ▪ Occasionally a minor variation in the sequence may occur. ▪ Use the rule: “I always appears before T”. So, if you see the ossified T before the I then the internal epicondyle has almost certainly been avulsed and is lying within the joint… ie it is masquerading as the trochlear ossification centre (see p. 105).

Paediatric elbow

Anatomy

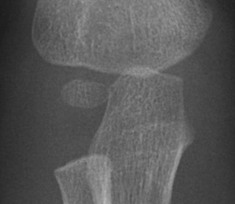

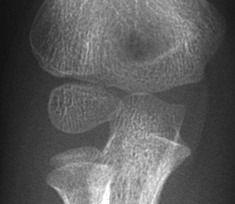

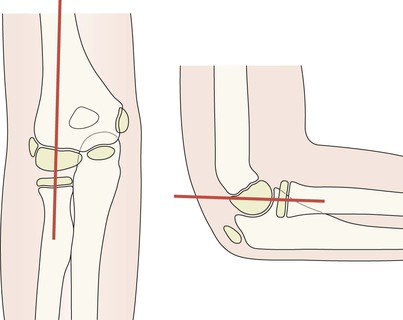

AP view—child age 9 or 10 years

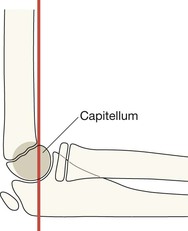

Lateral view—child age 9 or 10 years

Elbow fat pads

AP and lateral: the CRITOL sequence

CRITOL: the sequence in which the ossified centres appear

Exceptions to the CRITOL sequence?

Conclusions

Paediatric elbow

7