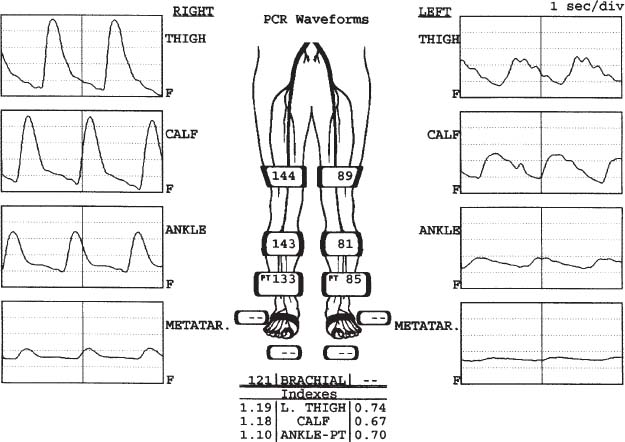

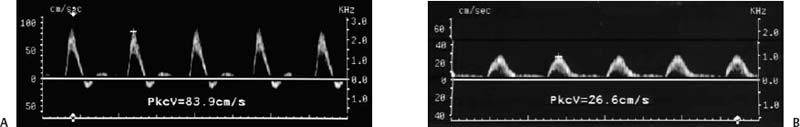

2 Painful Legs after Walking Leg pain after walking immediately brings to mind intermittent claudication resulting from arterial insufficiency, but it is important to recognize that other disorders also may cause leg pain after walking, including neuropathy, sciatica, acute venous thrombosis, chronic venous insufficiency, rupture of a popliteal cyst, and muscular hematoma.1–4 The starting point for differentiating among the possible causes of walking-related leg pain is the history and physical examination (H&P). For certain diagnoses, including arterial insufficiency, the H&P is generally quite specific and useful. For other causes of leg pain, however, the H&P findings are nonspecific and do not permit definitive diagnosis. Furthermore, the H&P may be nondiagnostic when two conditions coexist, both of which might cause leg pain (e.g., arterial insufficiency and peripheral neuropathy). In such circumstances, it may be difficult to determine which condition is causing the symptoms. This chapter reviews the clinical diagnosis of arterial insufficiency, with emphasis on the role played by duplex ultrasound (imaging combined with Doppler) and other diagnostic methods. First the capabilities and limitations of the major diagnostic methods, including ultrasound, are described, followed in some detail by the ultrasound methods and diagnostic parameters used for evaluating the lower extremity arterial tree, and then postprocedure ultrasound surveillance after surgical bypass grafting and angioplasty. As already noted, the patient’s history is often quite helpful in cases of arterial insufficiency because the patient describes a fairly specific symptom complex called intermittent claudication. The term claudication is derived from a Latin word for limping or lameness.5 Intermittent claudication refers to leg pain, weakness, or other discomfort that is absent at rest, commences after a period of ambulation, and subsides promptly when the patient stops walking.1–4 In most instances, intermittent claudication is a sign of arterial insufficiency. At rest, the circulation is sufficient to meet the metabolic demands of the leg muscles and other tissues, but blood flow is insufficient to keep up with the metabolic demands of exercise. Lactic acid and other metabolites accumulate in the ischemic muscles, causing cramping pain. Because intermittent claudication occurs specifically in areas of muscle ischemia, the location of pain is a fairly good indication of the location of arterial obstruction. The most common site of intermittent claudication is in the calf, implying femoropopliteal arterial occlusive disease, or arterial obstruction in the tibial and peroneal arterial trunks of the calf. Claudication may also occur in the thigh, implying external iliac or common femoral artery obstruction, or in the buttock, implying aortic or common iliac artery blockage.1–4 The severity of arterial insufficiency is implied by the amount of exercise that results in claudication, and it is routine, therefore, to grade intermittent claudication according to the distance the patient can walk before symptoms develop or limit ambulation (e.g., one- or two-block claudication). Most patients with lower extremity arterial insufficiency present with typical intermittent claudication symptoms; however, atypical claudication symptoms also occur, including foot pain or burning. These atypical symptoms are particularly confusing from a diagnostic perspective because they could be due to conditions other than arterial insufficiency, such as diabetic neuropathy or spinal nerve root compression resulting from degenerative disease of the lower lumbar spine. The clinical diagnosis of arterial insufficiency is also based on physical examination of the extremities.1–4 Arterial pulses in the foot are diminished or absent, depending on the degree of arterial obstruction. Other findings include absence of leg hair and coolness of the skin. With severe arterial insufficiency, rubor (redness of the skin) may be evident in the leg and foot with the limb dependent, accompanied by pallor of the skin when the leg is elevated. Moderate or severe arterial insufficiency is generally easy to diagnose clinically, but mild arterial insufficiency often cannot be confirmed clinically, especially when the only physical finding is diminished pulses—a subjective determination. Clinical assessment is further hampered when symptoms produced by other conditions mimic those of arterial insufficiency, as mentioned previously. Finally, clinical evaluation is inherently qualitative (subjective). A stoic patient may describe mild symptoms that another patient would describe as moderate or severe, and one clinician’s assessment of disease severity may vary from another. Such problems make it difficult to compare one patient’s condition with another and also complicate the assessment of disease progression over time. Figure 2–1 Physiological study. Segmental pressure and plethysmo-graphic examination reveals left lower extremity arterial insufficiency resulting from inflow (iliac) obstruction. At all levels on the left, the systolic blood pressure is significantly reduced and pulse volume waveforms are damped. The left ankle/brachial index is 0.70, consistent with mild claudication. There is no evidence of arterial insufficiency on the right. The deficiencies of clinical evaluation (H&P) led to the development of physiological tests for the assessment of lower-extremity arterial insufficiency,1–4,6,7 including the ankle/brachial index (ABI), segmental pressure measurements (thigh, calf, ankle, foot), plethysmography (which measures changes in limb volume with each arterial pulse), and Doppler waveform analysis (Fig. 2–1, Fig. 2–2). Tread-mill ambulation may be incorporated with these examinations to evaluate the capacity of the arterial system to respond to increased metabolic demand. The physiological tests serve well to answer several important questions, as listed below, that are not adequately addressed by clinical evaluation. 1. Are the patient’s symptoms truly due to arterial insufficiency or should another cause be sought? A normal resting ABI, coupled with a normal postexercise ABI response, effectively excludes arterial insufficiency as a cause of ambulation-related symptoms. 2. How severe is arterial insufficiency? Pressure measurements provide a reliable way of quantifying arterial insufficiency and a fairly precise way for comparing one patient’s condition with another’s. For example, an ABI of 0.7 or 0.8 generally corresponds to mild arterial insufficiency and relatively mild claudication, whereas an ABI of 0.4 or less corresponds to severe arterial insufficiency, possibly with rest pain. Figure 2–2 Doppler extremity arterial evaluation. (A) The normal, triphasic arterial signal in this common femoral artery suggests an absence of arterial insufficiency. Peak systolic velocity (PkcV) is within the normal range (Table 46–1). (B) The damped resting arterial waveform in this popliteal artery indicates arterial obstruction proximal to the examination site. Note the broad systolic peaks, slow upstroke in systole, low PkcV, and forward flow in diastole. 3. Is arterial insufficiency stable or progressing? Physiological studies provide quantitative data that are more reliable than changes in symptomatology. In some cases the patient may describe lessening of symptoms, yet physiological tests show worsening of arterial insufficiency, and vice versa. 4. Has the patient responded to therapy? The effects of medical or surgical therapy can be gauged quantitatively with physiological tests. The principal disadvantage of physiological studies is the limited information these methods provide about the extent and location of arterial obstruction. These methods also do not differentiate effectively between arterial stenosis and occlusion. Historically, catheter angiography was required to accurately determine the location and severity of arterial obstruction for purposes of surgical planning. More recently, however, noninvasive angiography and duplex ultrasound have emerged as the predominant methods for definitive evaluation of arterial insufficiency. Initially, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)8 appeared to have greater potential than computed tomo-graphic angiography (CTA)9 for lower-extremity arterial diagnosis, but the recent introduction of multidetector-row computed tomography (CT) has given the edge to CTA. Diagnostic-quality images of the entire lower extremity arterial tree can be obtained with CT within the time taken for a bolus of iodinated contrast to flow from the aorta to the feet. Similar diagnostic quality can be obtained with MRA, which offers the advantage of a less nephrotoxic contrast agent; however, the time frame for MRA examination is longer than that for CT. Owing to advancements in MRA and CTA, catheter-based angiography will soon virtually disappear from the diagnostic armamentarium for extremity arterial disease in Western nations, and arterial catheterization will be used only for therapeutic measures. The clinical utility of duplex ultrasound for lower-extremity arterial diagnosis10–42 was advanced significantly by the development of color Doppler and power Doppler flow imaging; nevertheless, duplex examination of extremity arteries can be arduous and time consuming. Iliac artery imaging may be significantly limited by interference from bowel contents, as well as vessel tortuosity. The femoral and popliteal arteries are relatively easy to examine, but even here difficulties may arise if there are multiple areas of obstruction or if the vessels are heavily calcified. Duplex examination of calf arteries (anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal arteries) is limited by the small size of the vessels, acoustic shadows from calcification, and difficulty in identifying/following diseased arteries.13 Even the use of ultrasound contrast agents does not substantially improve duplex results for calf vessel evaluation.14 These technical limitations have, in general, restricted the use of duplex sonography to relatively focused objectives, rather than comprehensive assessment of lower-extremity arterial disease. However, some centers do use duplex ultrasound routinely for comprehensive surgical planning and report excellent results, in terms of both examination success and surgical outcome. Advocates of comprehensive duplex arterial evaluation point out that ultrasound is cost-effective and noninvasive, and can be done in a clinical outpatient setting without the need for specialized facilities.15–19 These advantages notwithstanding, most medical facilities continue to use ultrasound in a more tailored way, to answer specific questions raised by the H&P, physiological studies, or arteriography. The following are examples of clinical questions that can be addressed with this approach. 1. Where are significant arterial obstructions located? As noted previously, the H&P and physiological tests provide some information about the location of arterial occlusive disease, but this information may be quite sketchy. In addition, it may not be clear whether the disease is localized or diffuse, or whether the problem is stenosis or occlusion. An example is the patient with reduced upper thigh pressure on a segmental pressure examination. It may be unclear if obstruction is in the iliac system, the common femoral artery, the superficial femoral artery, or in more than one area. This information can be conveniently obtained with duplex examination of the common femoral artery and the origin of the superficial femoral artery, possibly supplemented with direct evaluation of the iliac arteries. 2. Is an arterial segment stenotic or occluded? Duplex sonography can reliably differentiate between arterial stenosis and occlusion, which is something that physiological tests and physical examination cannot do accurately. 3. Is there an iliac artery obstruction that is amenable to angioplasty? Iliac lesions are generally considered amenable to angioplasty when they are localized (not multisegment), less than 5 cm in length, and reduce the lumen diameter by at least 50%.16 Eighty percent of iliac artery stenoses can be adequately evaluated with ultrasound, and the concordance between sonography and angiography is 92% for determining if the stenosis can be treated with angioplasty or is better treated surgically.15–19 4. Is an arteriographically identified stenosis hemodynamically significant? Even when carefully performed, CTA, MRA, or catheter arteriography may produce indeterminate results regarding the hemodynamic significance of stenotic lesions. Duplex examination of the arteriographically equivocal stenosis may be very useful for assessing the hemodynamic significance of such lesions, facilitating interventional or surgical planning. 5. What is the status of potential run-off vessels in the calf? Arteriography, regardless of the method used, sometimes fails to adequately define the presence, condition, and length of potential arterial bypass run-off vessels in the calf. Although duplex sonography, as noted previously, is far from perfect for evaluating infrapopliteal arteries,13,20 it can visualize some infrapopliteal arteries with great clarity when the vessels are relatively disease free and not heavily calcified. Thus, ultrasound is sometimes very useful as a means for determining which of the three main arterial trunks in the calf (anterior tibial, posterior tibial, or peroneal arteries) are patent, and which is sufficiently disease-free for use as a bypass target. 6. Is a pseudoaneurysm or arteriovenous fistula present? Pseudoaneurysms (false aneurysms or pulsating hematomas) and arteriovenous fistulas may be caused by violent or iatrogenic trauma (usually in the context of cardiac catheterization or angiographic procedures). These conditions cannot be accurately diagnosed clinically, but are readily detected with ultrasound. 7. Guidance for angioplasty. In recent years, it has become apparent that ultrasound is an excellent means for directing angioplasty in both the iliac and femoral arteries. Eighty percent of angioplasties can be completed successfully with ultrasound guidance alone, assuming that preprocedure case selection (see earlier discussion) is thorough.21 Ultrasound performs as well as angiography for determining balloon size, monitoring guidewire passage, directing dilatation, and judging procedure success. 8

Diagnostic Evaluation for Arterial Insufficiency

History and Physical Examination

Tests Other than Imaging Tests

Imaging Tests Other than Ultrasound

Magnetic Resonance Angiography and Computed Tomographic Angiography

Duplex Ultrasound Imaging

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree