and Gustavo Marino2

(1)

Attending Physician VA Medical Center, George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

(2)

Chief Gastroenterology Section VA Medical Center, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

6.1.1 Technique

6.1.3 Anatomic Considerations

6.1.3.1 Ventral and Dorsal Pancreas

6.2.2 Chronic Pancreatitis

6.2.7 Pancreatic Cancer

6.2.9 Pancreatic Tail Mass

6.2.12 Small Pancreatic Cancer

6.2.13 Isodense Pancreatic Cancer

6.2.16 Missed Pancreatic Cancer

6.2.20 Neuroendocrine Tumors

6.2.21 Primary Pancreatic Lymphoma

6.2.23 Pancreatic Cysts

6.2.23.3 Pancreatic Pseudocyst

6.2.24 Serous Cystadenoma

Abstract

A complete description of the endoscopic technique is available in most textbooks about endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). We recommend study of video recordings to review these techniques and endoscopic maneuvers and develop a systematic approach that goes through the standard EUS stations (body of the stomach, antrum, duodenal bulb, descending duodenum, and third portion of the duodenum), starting at the landmark structures of each station to achieve a complete exam. This systematic approach minimizes the risk of missed lesions or false interpretation of normal variants as abnormalities or masses.

Box 6.1: Resources

Ian Penman (editor) (eBook)

Meenan J. EUS: pancreatobiliary. In: Penman I (editor). Endoscopic Ultrasound. Wiley-Blackwell and GastroHep.com; 2013 http://www.gastrohep.com/ebooks/ebook.asp?book=1405120819&id=5

Medical University of South Carolina Digestive Disease Center: EUS Atlas: Normal Anatomy (images) http://www.ddc.musc.edu/professional/education/atlases/EUSatlas/normalAnatomy.cfm

Medical University of South Carolina Digestive Disease Center: EUS Video Atlas http://www.ddc.musc.edu/professional/education/atlases/EUSvideoAtlas.cfm

Medical University of South Carolina Digestive Disease Center: Normal pancreas exam during endoscopic ultrasound (used as reference to demonstrate absence of signs of chronic pancreatitis), Drs. G. P. Althal and M. Wallace, Medical University of South Carolina http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jos33wotYRg

EUS examination of the pancreas, Dr. Shyam Varadarajulu (uploaded by Boston Scientific) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S0UGyD5JGqA

EUS FNA demonstration of fanning technique, Dr. Shyam Varadarajulu (uploaded by Boston Scientific) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RcLhvSdCXtc

Dave Project – Gastroenterology: Multiple cases demonstrating the use of EUS in pancreatic pathology http://daveproject.org/category/pancreas/

World Endoscopy Organization: EUS and FNA of a complex pancreatic cystic neuroendocrine tumor by Dr. William R. Brugge, Massachusetts General Hospital http://www.worldendo.org/weo-video-william-brugge.html

6.1 General Principles

6.1.1 Technique

A complete description of the endoscopic technique is available in most textbooks about endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). We recommend study of video recordings to review these techniques and endoscopic maneuvers and develop a systematic approach that goes through the standard EUS stations (body of the stomach, antrum, duodenal bulb, descending duodenum, and third portion of the duodenum), starting at the landmark structures of each station to achieve a complete exam. This systematic approach minimizes the risk of missed lesions or false interpretation of normal variants as abnormalities or masses.

We cannot emphasize enough that to interrogate the pancreas with EUS the endosonographer must have a clear understanding of the normal anatomy of the retroperitoneal region, which provides specific landmarks that allow sonographic recognition of the pancreatic head, body, and tail as well as the surrounding structures.

6.1.2 Endoscopic Ultrasound Probes

Radial and linear scanning echoendoscopes are able to provide complete visualization of the pancreas from different planes of orientation. The preference of endoscope depends on training, experience, and personal preference. Ultrasound waves of lower frequencies (5–7.5 MHz) penetrate deeper, resulting in better visualization of the surrounding anatomy.

6.1.3 Anatomic Considerations

The splenic vein is easily identified from the body of the stomach and provides a good landmark reference given its direct contact with the pancreatic body and tail. This vein is usually found dorsal to the pancreas; it is confirmed and differentiated from other structures such as left renal vein by tracing it from the splenic hilum to the portal confluence. The celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery allow rapid identification of the pancreatic body during linear EUS because the pancreas lies ventral to the superior mesenteric artery.

The portal vein is a key landmark for the identification of the pancreatic head at the duodenum and can be traced from its confluence to the hepatic hilum. The bile duct can also be identified and followed from the major papilla to the hilum. In the case of biliary obstruction, EUS provides excellent information and allows identification of intraductal lesions or defects, mural thickening, or extrinsic compression and masses. Other important structures that require EUS evaluation from the duodenum include the superior mesenteric artery and vein.

6.1.3.1 Ventral and Dorsal Pancreas

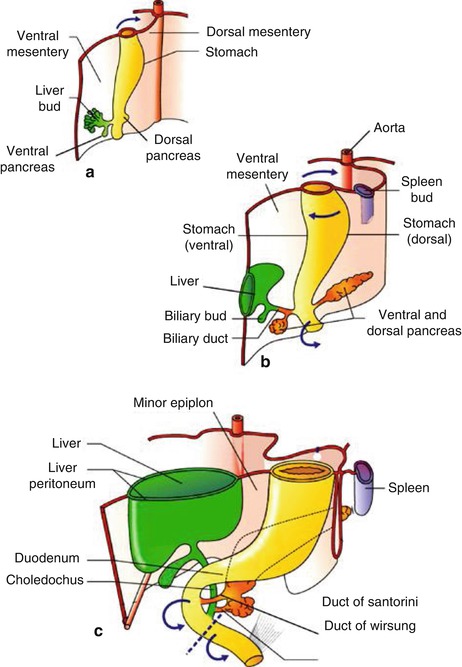

The embryologic pancreas consists of a dorsal bud and a ventral bud or anlage. The dorsal bud arises as a diverticulum of the dorsal aspect of the duodenum (hence the name). The ventral anlage originates as a common diverticulum with the primitive common bile duct (see Fig. 6.1). At 6 weeks the ventral bud rotates 270 degrees to lie posterior and inferior to the dorsal bud (Fig. 6.1b). Fusion of these two buds forms the mature pancreas. In most individuals there are subtle differences in the density on computed tomography (CT), intensity on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or echogenicity between these two components, which border each other in the head of the pancreas. The less echogenic ventral pancreas contains less fat than the embryologic dorsal pancreas. The difference is noticeable in up to 25 % of normal individuals using abdominal CT or transcutaneous ultrasound [1, 2]. This difference is more frequently detected by EUS; it has been reported in 72 % of patients with normal parenchyma and 29 % of patients with a clear mass or chronic pancreatitis [3]. In the first case below (Acute Pancreatitis with an Edematous Head of Pancreas), a hypodense area of the pancreas was observed (see Fig. 6.2) and the patient was referred for EUS, which showed no mass but the typical differences in echogenicity seen between the ventral and dorsal pancreas. This EUS finding should be easily recognized and not confused with chronic pancreatitis or malignancy.

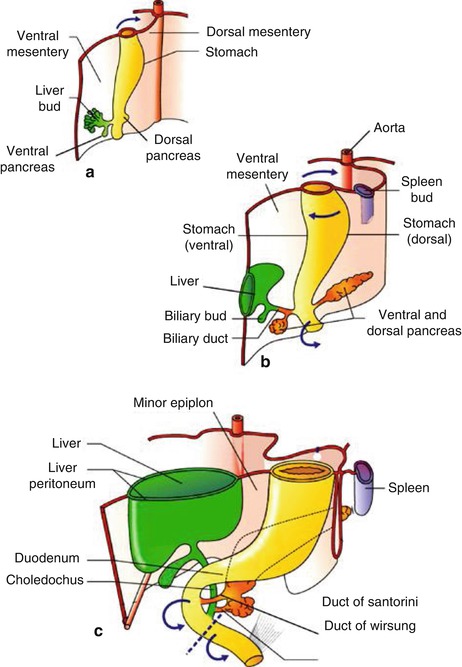

Fig. 6.1

Development of the pancreas in human embryos at 5 (a), 6 (b), and 7(c) weeks. Arrows indicate the sense of rotation of the primitive intestine around its longitudinal axis. Broken line, limit between foregut and midgut (From Rovasio [4])

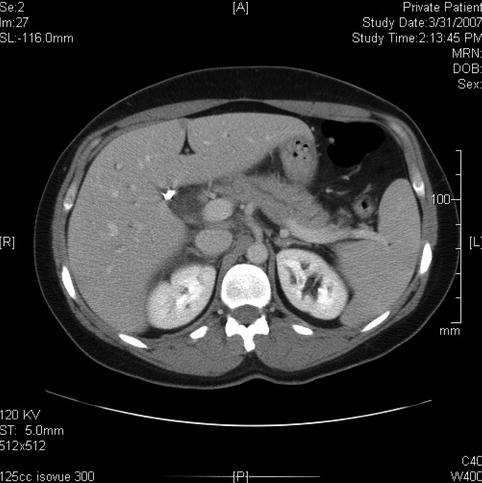

Fig. 6.2

There is a hypodense area in the head of the pancreas (indicated by the yellow line)

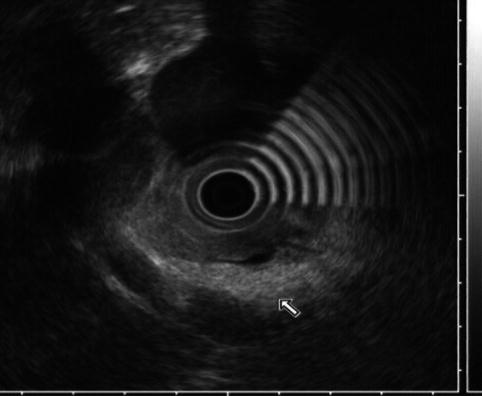

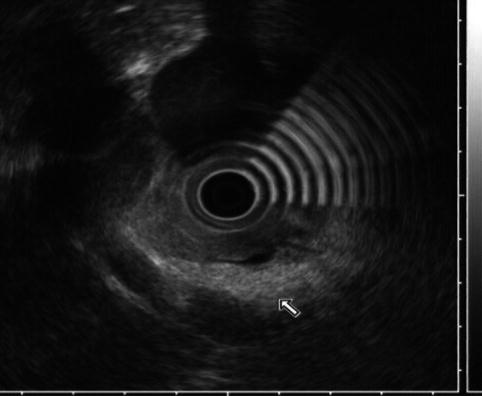

Fig. 6.3

This endoscopic ultrasound image shows a clear demarcation between echo-rich (dorsal, arrow) and echo-poor (ventral) pancreas

6.2 Cases and Discussions

6.2.1 Acute Pancreatitis with an Edematous Pancreatic Head

This is a 39-year-old woman admitted to the hospital with acute pancreatitis. At admission her lipase level was 1,238 U/l, but it fell to 210 U/l the following day. She has had a cholecystectomy. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed by a different examiner on the day after admission and only the pancreatic duct was injected. The bile duct could not be cannulated. Following the ERCP her lipase level increased from 210 to 7,068 U/l, which his most consistent with pancreatitis after ERCP superimposed on acute spontaneous pancreatitis. An magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) then was ordered and showed “a dilated tapered common bile duct” but was otherwise unremarkable. Two days later CT was requested to evaluate for pseudocysts. Curiously, the radiologist reported dilation of the bile duct to 2 cm and a “double duct sign” with a dilated pancreatic duct. The clinicians were worried about a pancreatic malignancy and requested clarification by EUS. Performed on the third day after failed ERCP, which had resulted in pancreatitis, EUS showed compression of the intrapancreatic portion of the common bile duct, a normal pancreatic duct, and cystic spaces in the head of the pancreas consistent with acute pancreatitis.

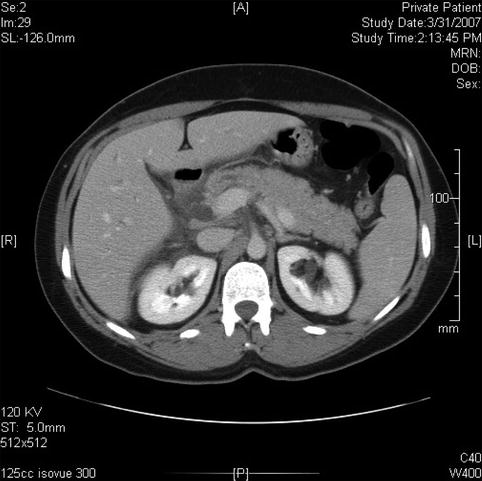

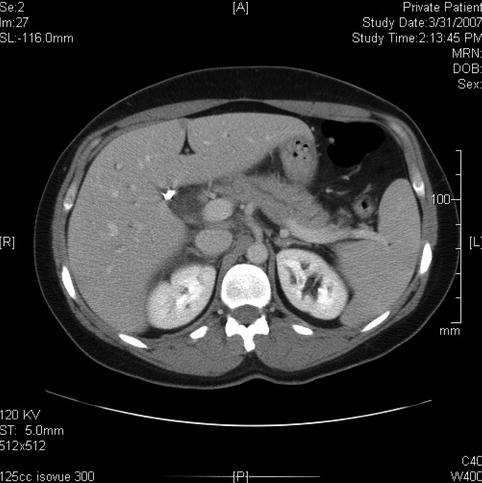

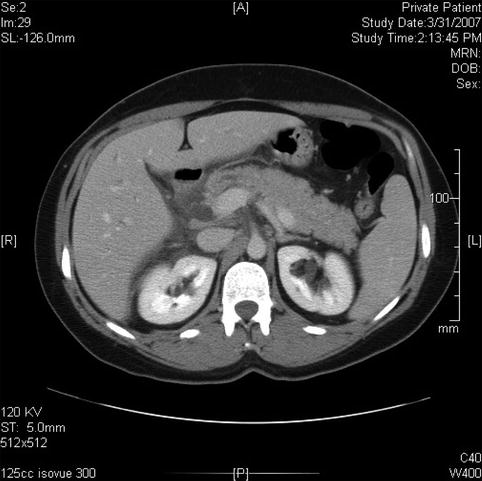

Fig. 6.4

This computed tomography scan seems to show a dilated bile duct (20 mm), but in fact the cystic duct and bile duct are so close together that they were measured as one structure

Fig. 6.5

This is the extrapancreatic portion of the bile duct; it is slightly prominent

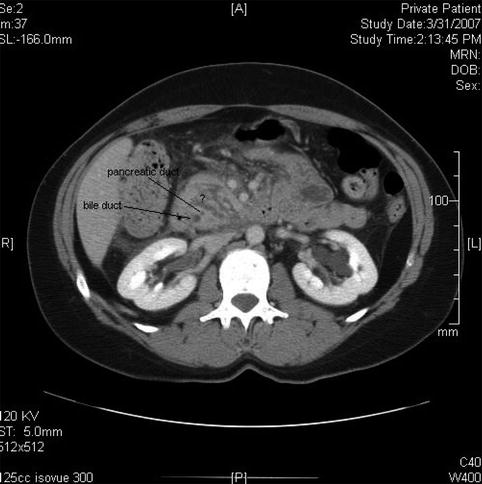

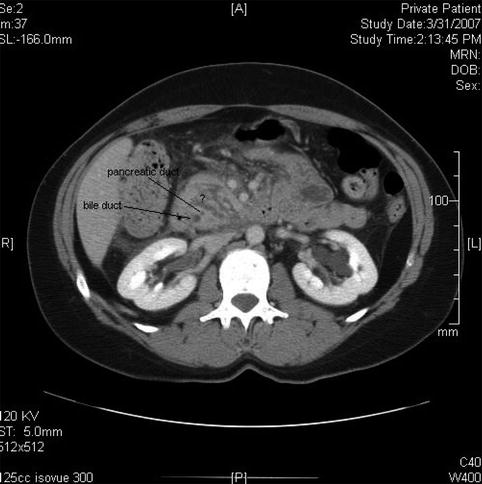

Fig. 6.6

The intrapancreatic segment of the bile duct is slender on this computed tomography scan and the pancreatic duct is certainly not dilated. The area marked by ? appears to represent intrapancreatic fluid spaces

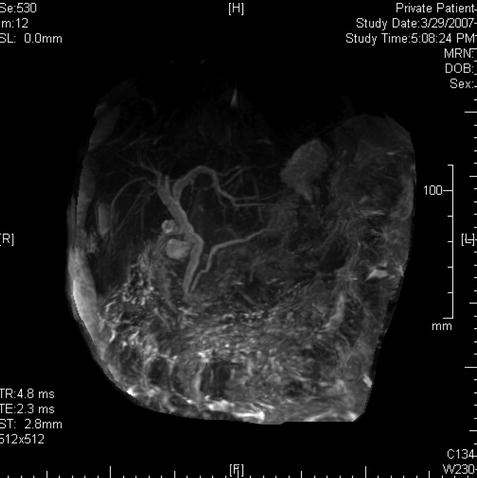

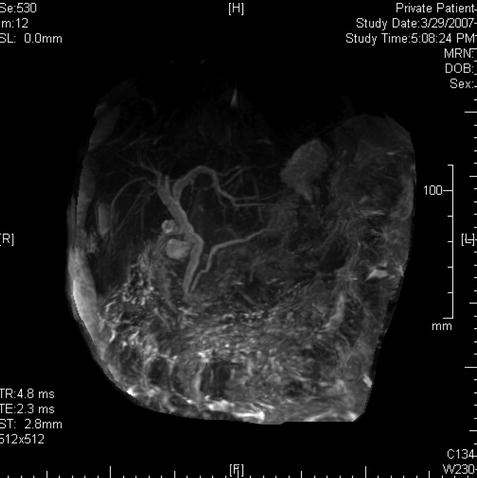

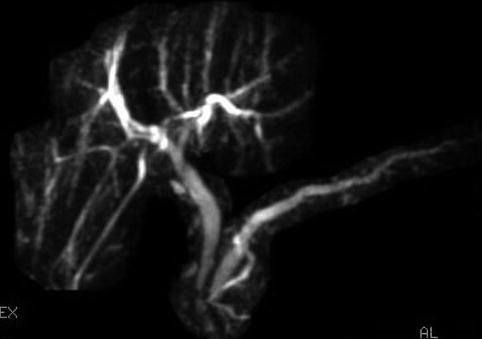

Fig. 6.7

This magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image is relatively uninformative: it does not show abnormalities of the pancreatic head or the cause of the mild dilation of the bile duct

Fig. 6.8

This endoscopic ultrasound image shows a prominent bile duct above the entrance into the pancreas

Fig. 6.9

Cystic spaces are seen in the head of the pancreas, which are also visible on the computed tomography scan

Fig. 6.10

Another image of the cystic areas, which probably represent the sequelae of acute pancreatitis

EUS is considered useful in the evaluation of acute pancreatitis of unclear etiology. In experienced hands it can provide excellent views of the extrahepatic bile ducts in more than 95 % of cases [5, 6], and it is frequently performed during the initial phase of pancreatitis to diagnose choledocholithiasis and better select patients who really need therapeutic ERCP, avoiding unnecessary risks. Studies evaluating EUS during an acute attack of pancreatitis have shown a sensitivity of 91–100 % and a specificity of 85–100 % in diagnosing choledocholithiasis [7].

EUS has the potential to detect pancreatic ductal abnormalities during acute pancreatitis, although its role in this setting has not been completely evaluated [7]. The appearance of the pancreas during acute pancreatitis is variable: the size of the gland can be normal or enlarged, and its sonographic pattern is frequently described as hypoechoic but occasionally of normal echogenicity and sometimes hyperechoic or mixed. Small studies have attempted to describe the appearance of pancreatic necrosis as focal hypoechoic areas [8, 9], but these findings require validation in larger studies.

Once the acute attack has subsided, EUS can also be used to evaluate for causes of pancreatitis, including pancreatic and ampullary solid tumors, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, biliary sludge, and pancreas divisum.

6.2.2 Chronic Pancreatitis

6.2.2.1 Chronic Pancreatitis with a Stone in the Pancreatic Duct

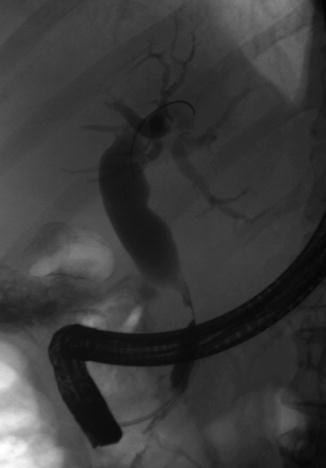

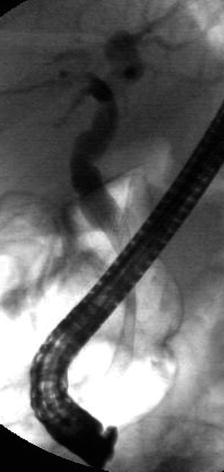

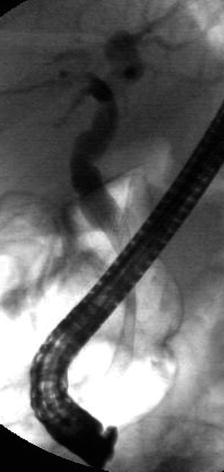

This is a 45-year-old patient with a history of excess alcohol use and a recent hospitalization for acute pancreatitis. The MRCP suggests a stone but only EUS clearly shows an 8-mm-diameter stone obstructing the main pancreatic duct. The pancreatic duct in the body measured 3.5 mm and had echo-rich borders. The parenchyma of the head area shows the characteristic hyperechoic stranding of chronic pancreatitis. An ERCP was performed. The stone in the pancreatic duct was difficult to discern on the ERCP, underscoring the utility of EUS as imaging modality for pancreatic disease. Also note that the short area of narrowing above the stone can be appreciated both on the EUS and ERCP images. The calculus was successfully removed after a pancreatic sphincterotomy and the use of a balloon occlusion catheter. A temporary pancreatic stent was inserted.

Fig. 6.11

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography was somewhat equivocal about the presence of a stone

Fig. 6.12

A stone in the pancreatic duct in the head of the pancreas, close to the papilla

Fig. 6.13

Moderate chronic pancreatitis

Fig. 6.14

Pancreatic duct stone on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

6.2.3 Pancreatic Parenchymal Calcifications and Stone in the Pancreatic Duct

This is a 61-year-old patient with pancreatic parenchymal calcifications and a stone in the main pancreatic duct, which was destroyed with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, leading to significant improvement of her pain.

Fig. 6.15

Computed tomography scan showing pancreatic calcifications

Fig. 6.16

Dilated main pancreatic duct on endoscopic ultrasound

Fig. 6.17

Severe calcific pancreatitis with both intraparenchymal calcifications and a stone in the pancreatic duct

Fig. 6.18

A stone in the pancreatic duct

The diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis can be challenging in patients with inconclusive noninvasive imaging and focal changes that cannot be easily differentiated from pancreatic cancer. ERCP has a low sensitivity in the diagnosis of early chronic pancreatitis, and an abnormal pancreatogram has poor specificity, as confirmed in studies of elderly patients and autopsy studies [10, 11]. CT findings including calcifications and ductal abnormalities are considered specific but not sensitive for mild to moderate disease [12]. One of the most common situations is the presentation of chronic abdominal pain with normal-appearing pancreas on CT or MRI/MRCP in patients with histologic inflammation and fibrosis; this presentation is the so-called minimal-change chronic pancreatitis.

Histologic confirmation is the gold standard for diagnosis but is too invasive and rarely possible. In many patients a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis can be achieved by EUS and a variety of criteria, such as structural abnormalities of the parenchyma or the pancreatic ducts, or by performing hormone-stimulated pancreatic function tests in conjunction with EUS [13]. In studies comparing EUS and histopathological diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, the sensitivity of EUS has been reported between 75 and 90 % and the specificity between 80 and 100 % [13–15]. Albashir et al. [13] have reported that combining EUS and secretin-stimulated pancreatic function tests can increase the sensitivity to 100 % (95 % confidence interval, 63–100).

Parenchymal EUS criteria include hyperechoic foci, hyperechoic strands, cysts, lobularity, and calcifications. Ductal EUS criteria include a hyperechoic duct wall, visible side branches, dilatation of the main pancreatic duct, and irregularity of the main pancreatic duct [16]. These criteria have been used without accounting for the greater diagnostic weight of some of them, such as calcifications/stones; a threshold of three to five criteria has been used to establish the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis by different authors; it is obvious that a greater number will maximize specificity and a lower number will maximize sensitivity. Some of the criteria, particularly hyperechoic strands, hyperechoic foci, irregularity of the main duct, and visible side branches, have a significant degree of interobserver variability (κ < 0.4) [17, 18].

Given these limitations, a consensus-based, weight-adjusted scoring system, called the Rosemont criteria, was developed in 2007 by a group of experts [19]. This system assigns a greater diagnostic value to pancreatic duct calculi, hyperechoic foci with shadowing, and lobularity with honeycombing. The Rosemont criteria still require validation before it can be implemented in standard EUS practice. A clear definition of EUS features of chronic pancreatitis was established by this group of experts as follows [19]:

Hyperechoic foci with shadowing: echogenic structures ≥2 mm in length and width that shadow

Hyperechoic foci without shadowing: echogenic structures ≥2 mm in both length and width with no shadowing

Lobularity: well-circumscribed structures ≥5 mm in size with an enhancing rim and relatively echo-poor center

Honeycombing: more than three contiguous lobules

Cysts: anechoic, rounded/elliptical structures with or without septations

Stranding: hyperechoic lines of ≥3 mm in length in at least two different directions with respect to the imaged plane

Main pancreatic duct calculi: echogenic structure(s) within main pancreatic duct with acoustic shadowing

Irregular main pancreatic duct contour: uneven or irregular outline and ectatic course

Dilated side branches: three or more tubular anechoic structures each measuring ≥1 mm in width and budding from the main pancreatic duct

Main pancreatic duct dilation: ≥3.5-mm body or >1.5-mm tail

Hyperechoic main duct margin: echogenic, distinct structure greater than 50 % of the entire main pancreatic duct in the body and tail of the pancreas

6.2.4 Fatty Infiltration of the Pancreas

Fig. 6.19

Pancreatic head. Is this chronic pancreatitis?

Fig. 6.20

Pancreatic body. This is not “stranding” but septation by fat

Fig. 6.21

Fatty infiltration of the pancreas, giving it a marbled or lobulated appearance

Fig. 6.22

Lobulated appearance of the pancreas seen at a higher frequency

Infiltration of fat in the pancreas and other organs such as the liver, heart, and striated muscle has been well described in obese individuals and those with insulin resistance [20]. This relation has been well documented in autopsy, CT, and MRI studies [21]. This condition was initially called pancreatic lipomatosis and, more recently, pancreatic steatosis; its clinical implications are still unclear, but it has been shown in some cases to precede the development of type II diabetes [20]. An association with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has been demonstrated, mostly in women, particularly related to the presence of intralobular pancreatic fat [22]. Given this association, the term nonalcoholic fatty pancreas disease has been proposed, suggesting a common pathophysiology related to insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. The exact clinical consequences of fatty infiltration of the pancreas are not known.

The diagnosis of pancreatic steatosis should be suspected in patients with markedly hyperechoic pancreatic parenchyma compared with the liver, but less prominent changes also can be found in normal patients. Some authors recommend additional pancreatic images (CT or MRI) to establish this diagnosis in these unclear cases [23].

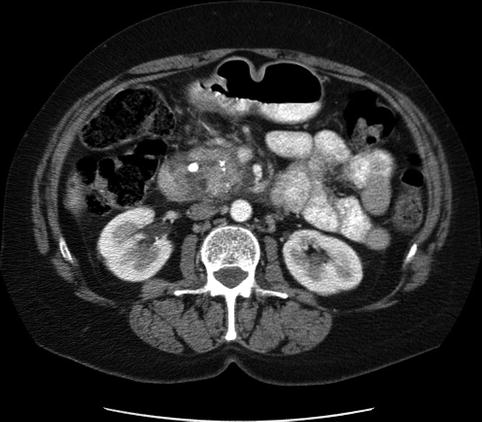

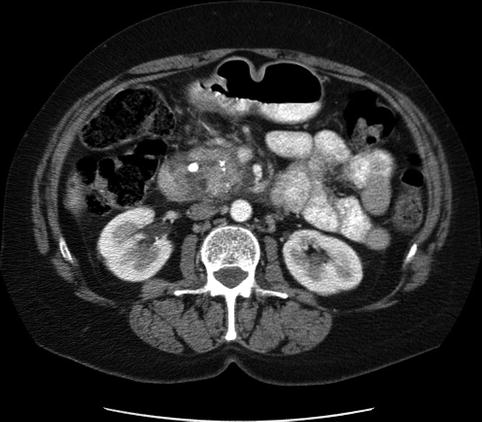

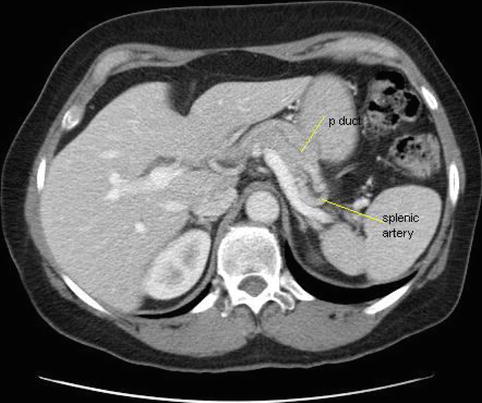

6.2.5 Perivascular Fat Mimicking a Dilated Main Pancreatic Duct

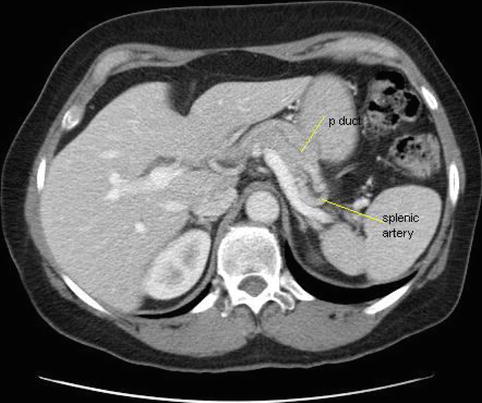

This is a 64-year-old patient who had CT for the evaluation of lower abdominal pain. The CT was interpreted as showing a focally dilated main pancreatic duct, and the patient was referred for EUS evaluation. EUS showed a degree of fatty infiltration of the pancreas but was otherwise unremarkable. Reanalysis of the CT scan shows that fat between the splenic artery and the pancreas was erroneously interpreted as the pancreatic duct. The pancreatic duct, as seen on the labeled CT, Fig. 6.26 takes off into another direction.

Fig. 6.23

This computed tomography scan shows what initially appeared to be focal dilation of the main pancreatic duct in the body of the pancreas

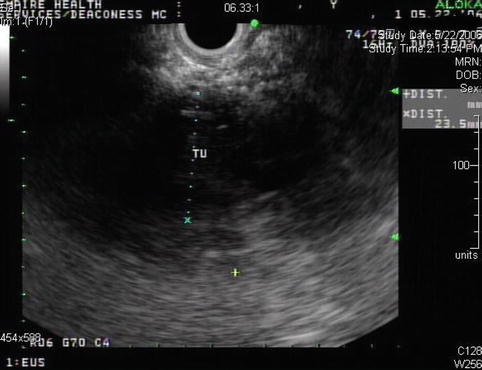

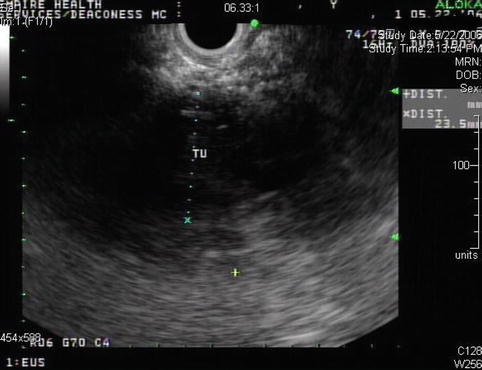

Fig. 6.24

This endoscopic ultrasound image shows some fatty infiltration of the pancreas but is otherwise unremarkable. The main pancreatic duct appears normal

Fig. 6.25

Another view shows no evidence of a dilated main pancreatic duct

Fig. 6.26

The computed tomography scan was reinterpreted in view of these findings: the dark structure hugging the splenic artery is perivascular fat

6.2.6 Vanishing Pancreatic Mass

This is an 88-year-old woman with a history of esophageal spasms and a Zenker’s diverticulum who presented to the emergency department with acute onset of epigastric pain. She was discharged from the emergency department after the pain had significantly improved. Laboratory tests were unremarkable; amylase and lipase levels were apparently not checked at the time. Three months later she returned and had a bilirubin level of 12 mg/dl. An ERCP showed a fairly long stricture in the distal common bile duct. A pancreatic head neoplasm was suspected, although CT of the abdomen was unremarkable except for bile duct dilation. EUS performed at the time showed an ill-defined hypoechoic mass suspicious for tumor, but the fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies were negative. Two months later the patient presented for a follow-up EUS. The jaundice did not recur after removal of the biliary stent. Her CA 19–9 level had decreased from 78 to 42 U/mL, making it likely that the elevation was related to the cholestasis. In place of the previously noted hypodense pseudotumor, small cysts/cystic spaces were now seen. Repeat FNA again was negative. In retrospect it seems that the patient had an unrecognized attack of acute pancreatitis with an inflammatory pseudomass that resolved into small pseudocysts.

Fig. 6.27

Ill-defined hypoechoic area with bile duct compression and jaundice. Is this a pancreatic tumor?

Fig. 6.28

Ill-defined hypodense area in the pancreatic head with a biliary stent

Fig. 6.29

Pseudomass followed by cyst in the same location in the head of the pancreas

Clinical presentation and imaging findings of pancreatic cancer and inflammatory masses of the pancreas, frequently due to chronic pancreatitis, can be similar and their differential diagnosis can be challenging. Both entities can cause pancreatic duct and biliary duct dilation, fluid collection, and lymphadenopathy [24]. Pancreatic cancer can occur in patients with underlying chronic pancreatitis, and these tumors can also be associated with peritumoral inflammatory changes. A variable proportion of patients referred for presumed pancreatic cancer are found to have inflammatory masses of focal pancreatitis [25].

Additional EUS-based techniques such as elastography and contrast enhancement are emerging techniques that may provide better accuracy than standard EUS in the evaluation of solid pancreatic lesions. These techniques are expected to minimize unnecessary FNA and improve diagnostic efficiency, although further research is still necessary to define their clinical roles [26, 27].

An aggressive workup, including FNA, of all suspicious lesions is recommended by some experts, given the morbidity and mortality of pancreatic resections of up to 30 % and 5 %, respectively, although better surgical results are obtained in large referral centers. On the other hand, arguments to not undergo preoperative biopsy in patients with potentially resectable masses and good operability include the fact that FNA/biopsies can be falsely negative in up to 10 % of cases and surgical delays are likely to allow the cancer to progress to more advanced stages that are no longer curable.

One of the concerns with FNA is the risk of tumoral seeding at the needle tract. This is not an issue with masses at the head of the pancreas, for which EUS-guided FNA is performed via a transduodenal approach because the duodenum is removed with the Whipple operation. A few reports of track seeding have been reported in patients undergoing transgastric FNA/biopsies of lesions at the body and tail of the pancreas [28, 29]; this risk seems to be very low given the scarcity of reports, but we recommend that it be discussed as part of the informed consent.

It is clear that FNA is appropriate in patients with large masses that appear to be unresectable so that a histologic diagnosis and the need for palliative therapy can be established. FNA is also appropriate in cases where the diagnosis is not clear based on history and imaging findings; as demonstrated in this case, inflammatory masses can have a presentation that is difficult to distinguish from pancreatic cancer.

6.2.7 Pancreatic Cancer

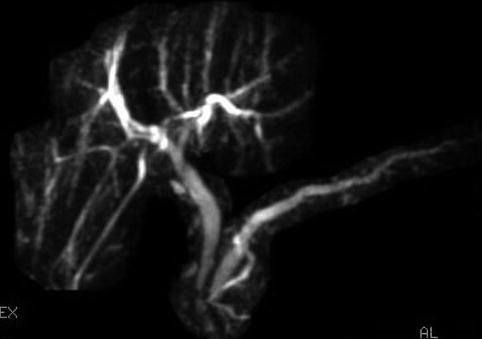

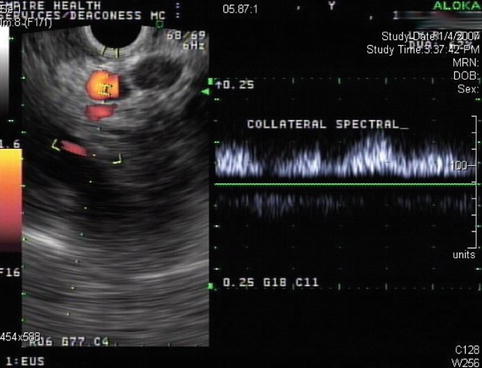

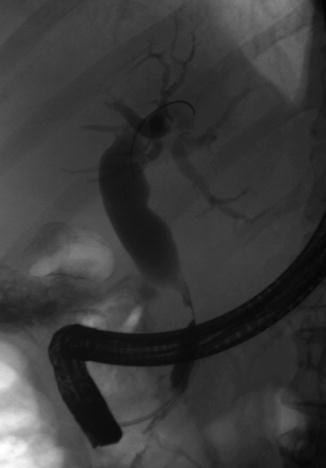

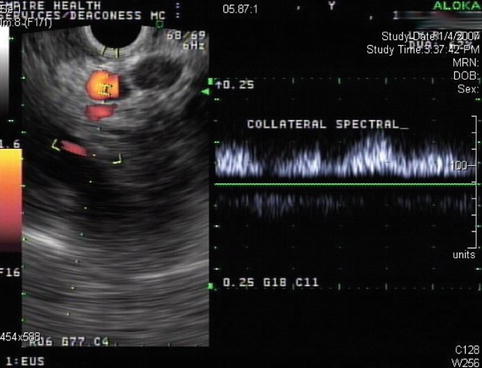

6.2.7.1 Stage IV Pancreatic Cancer with Extensive Collaterals

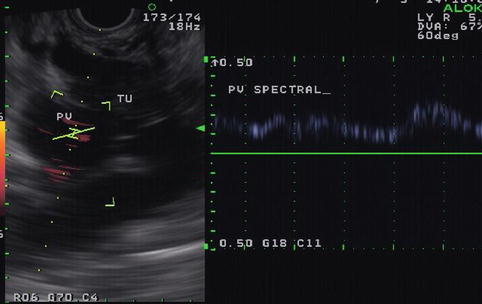

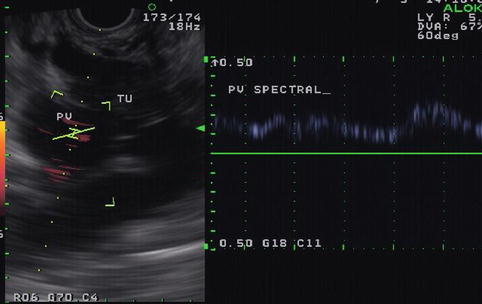

This is a 76-year-old patient with a large pancreatic mass with pulmonary metastases. CT showed ascites and extensive venous collaterals surrounding the pancreatic head. A percutaneous CT-guided biopsy was contemplated, but because of the venous collaterals in the biopsy path the patient was referred for EUS-guided FNA instead. Figures 6.31 and 6.32 show the corresponding EUS, which indicates a rather diffuse mass and two vessels next to it, both with a portal venous system spectral Doppler profile. One of them is the portal vein, and the other is a rather large collateral. Five passes were made into the mass, avoiding adjacent vessels.

Fig. 6.30

Bile duct stricture secondary to a pancreatic head mass

Fig. 6.31

This mass is fairly ill defined at its borders and appears to be diffusely infiltrative

Fig. 6.32

Power Doppler shows the portal vein and a large collateral

Fig. 6.33

Spectral Doppler confirms that this vessel belongs to the portal venous system

This case demonstrates one of the most common scenarios seen in the practice of EUS: a patient with obstructive jaundice secondary to advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. It is obvious that these patients are not candidates for surgical resection, and the goal of therapy is to provide palliative care. While biliary stents provide acceptable palliation of biliary obstruction, a tissue diagnosis is necessary to proceed with palliative chemotherapy and radiation, which helps to minimize abdominal pain and improve quality of life.

EUS has become the method of choice to obtain histologic diagnosis in this situation, where ERCP brushings are frequently falsely negative, and the same applies to percutaneous biopsies. EUS also provides the option to perform celiac plexus block/neurolysis to better control abdominal pain.

6.2.8 T2 Adenocarcinoma of the Pancreas

This is a 90-year-old patient with a 2.2-cm mass in the head of the pancreas and obstructive jaundice. The gallbladder is massively distended. Note the attachment of the tumor to the portal vein but no signs of invasion. EUS-guided FNA biopsies were performed and a Wallstent was placed the following day.

Fig. 6.34

Distended gallbladder in biliary obstruction

Fig. 6.35

Pancreatic mass on endoscopic ultrasound

Fig. 6.36

Doppler study showing a portal vein pancreatic mass

Fig. 6.37

The mass as it relates to the portal vein

Fig. 6.38

A Wallstent bridging the biliary stricture

A palliative approach is also recommended in this 90-year-old patient. In this case a surgical resection would be feasible in expert hands, even with some limited involvement of the portal vein; however, a decision was made to avoid surgery because of the patient’s advanced age and existing comorbidities. EUS provided cytological diagnosis and tumor staging; once diagnosis of tissue malignancy was confirmed the patient underwent ERCP with placement of a self-expandable, uncovered metal stent.

It is important to remember than uncovered biliary metal stents are not removable and they are only approved for malignant indications. Fully covered metal biliary stents that can be removed are now available and have been used safely for benign biliary disease; unfortunately they are associated with more frequent complications, particularly migration, compared with uncovered metal stents in the management of distal malignant biliary obstruction [30]. Therefore, we recommend that the evaluation of patients be started with EUS and include histologic confirmation to establish a clear diagnosis before ERCP and stent placement.

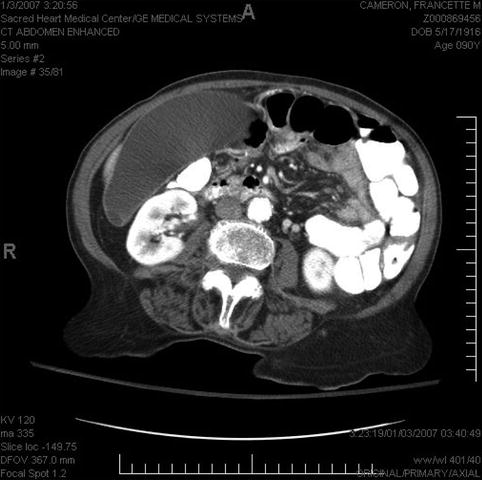

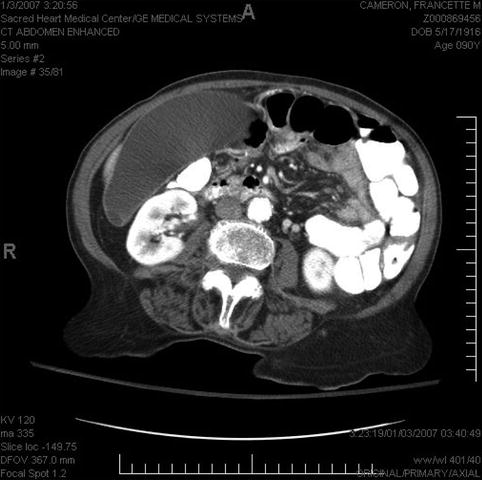

6.2.9 Pancreatic Tail Mass

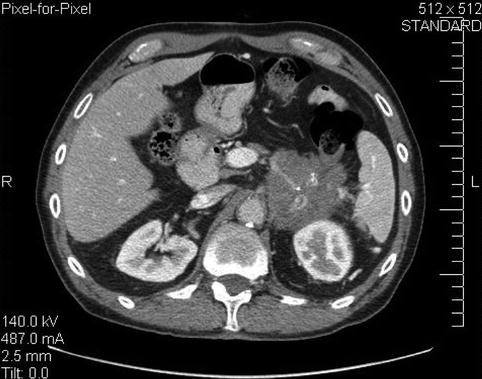

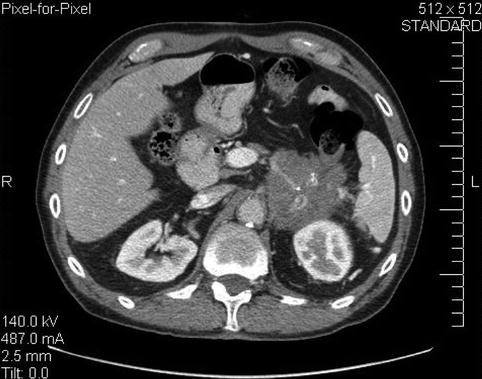

This is a 75-year-old man who has not been feeling well for approximately 2 months; he is complaining of epigastric pain and a 15-lb weight loss. CT of the abdomen showed a large pancreatic tail mass (6 cm in diameter), which had led to splenic vein thrombosis with gastric collaterals, retroperitoneal invasion, and an apparent adrenal metastasis. Corresponding EUS and CT images are shown in Figs. 6.39 and 6.40, respectively. This case highlights that pancreatic tail cancers can grow to a large size before becoming symptomatic. They also are more likely to have metastasized to the liver by the time they are discovered. This tumor also illustrates an infiltrating growth pattern with tumor pseudopodia that may reflect a more aggressive tumor biology. EUS-guided FNA biopsies were positive for adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 6.39

A 6-cm-diameter mass in the pancreatic tail infiltrating into the retroperitoneum

Fig. 6.40

Endoscopic ultrasound appearance of the pancreatic mass. Very large masses sometimes fill the entire field of view. Care must be taken to see the forest in spite of all the trees

Fig. 6.41

A different level of the computed tomography shows an enhancing mass in the region of the adrenal

Fig. 6.42

The left adrenal is shown with a central tumor. The inset shows a contrast-enhanced negative image of it

6.2.10 Calcifications in a Hypoechoic Pancreas Tumor

Hypoechoic masses, especially in patients with underlying chronic pancreatitis, may be benign or malignant and may represent inflammation, neoplasia, or relative sparing from the chronic pancreatitis in that location. In patients with an otherwise normal pancreas, calcifications in a hypoechoic mass do not indicate benign disease, as this case demonstrates. In the majority of cases pancreatic calcifications are seen in chronic pancreatitis. However, they occur infrequently in pancreatic adenocarcinomas without pre-existing chronic pancreatitis.

Fig. 6.43

Isolated pancreatic calcifications in a hypoechoic pancreas mass do not establish a diagnosis of benign disease (radial endoscopic ultrasound using a GF-UE160 echoendoscope)

Fig. 6.44

The linear endoscopic ultrasound echoendoscope reveals a different aspect of the same tumor shown in Fig. 6.43 (carcinoma proven by biopsy). Note the fluffy calcifications in the tumor mass

6.2.11 Chronic Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer

This patient had presented elsewhere a year earlier with a pancreatic pseudocyst that resolved. Over the past 6 months he had lost approximately 40 lb of weight and eventually was not able to eat but had no jaundice. CT showed chronic calcific pancreatitis with a dilated and irregular pancreatic duct, gastric outlet obstruction, a dilated bile duct, and a mass in the pancreatic head. EUS showed a relatively small (2.8 cm) tumor in the head of the pancreas close to the duodenum that had infiltrated into the duodenum, causing gastric outlet obstruction symptoms. While this tumor could have originated from the duodenum and grown into the pancreas, it was felt that most imaging was consistent with a pancreatic head primary tumor.

Fig. 6.45

This radial endoscopic ultrasound image demonstrates a dilated bile duct and gallbladder as well as circumferential invasion of the duodenum by tumor

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree