Normal Anatomy

The pancreas is mostly within the retroperitoneum in the anterior pararenal space. However, the tail of the pancreas is actually an intraperitoneal structure and in close relationship with the splenorenal ligament. To best understand the anatomy of the pancreas, an understanding of embryology is necessary. The pancreas develops from two pancreatic buds: the dorsal bud and the ventral bud. With development, the ventral bud of the pancreas rotates posterior to the duodenum and becomes the uncinate process. The dorsal bud comprises most of the pancreas. The main pancreatic duct usually enters with or in close proximity to the common bile duct into the duodenum at the major papilla, through the duct of Wirsung. The distal part of the dorsal pancreatic duct forms the duct of Santorini and can persist as an accessory pancreatic duct and enters the duodenum at the minor papilla. On occasion, the entire pancreatic duct enters the duodenum through the accessory duct of Santorini. When this anatomic variant is found with the ventral and dorsal pancreatic ducts not fusing, this is termed pancreatic divisum . This important to note, as this can be an etiology of acute and/or recurrent pancreatitis.

In most adults, the anterior/posterior dimension of the pancreas can vary from 2.0 to 3.0 cm in thickness. The head of the pancreas is anatomically in close approximation to the “C” loop of the duodenum. The splenic vein forms the posterior margin of the pancreas and joins the superior mesenteric vein in the region of the head or neck of the pancreas ( Fig. 18.1 ). The uncinate process projects posteriorly from the pancreatic head. The neck is the thinnest portion of the pancreas and is the region between the body and the head, usually at the confluence of the splenic and superior mesentery vein. The superior mesenteric artery is noted posterior to the pancreas. It can be recognized by the mesenteric fat surrounding it.

Ultrasound Techniques/Findings

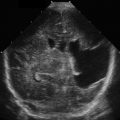

The pancreas is usually fairly homogeneous in appearance. A scanning window is provided through the left lobe of the liver. Often, the partially collapsed stomach or pylorus of the stomach can be seen. The muscular wall of the stomach will be hypoechoic and can be confused with the pancreatic duct. The pancreas is often obscured by bowel gas, and as such moderate probe pressure is utilized. The body of the pancreas is the portion of the pancreas most commonly identified. Visualization of the head of the pancreas may be aided by using a right subcostal approach and angling the transducer medially. The tail of the pancreas is often difficult to identify but may be aided by having the patient drink de-gassed water. Within the head of the pancreas, the gastroduodenal artery is seen anteriorly, whereas the common bile duct is seen more posteriorly in the pancreatic head ( Fig. 18.2 ). The pancreatic duct can be seen in normal patients. The superior mesenteric vein joins the splenic vein and is noted posterior to the pancreas. The superior mesenteric artery is seen as a rounded structure, which is recognized by the echogenic mesentery fat surrounding it (see Fig. 18.2 ).

The pancreas is just as or slightly more echogenic than the liver. With age, there can be a change in the size and echogenicity of the pancreas. If there is gradual atrophy of the pancreas, there may be fatty replacement of the pancreas with fibrosis and fat, which increases the echogenicity of the pancreas. Pancreatic atrophy may be better identified with computed tomography (CT). The pancreas may be seen not only with a transverse scan but also with a parasagittal scan. Depending on the parasagittal plane that is used, the liver and the stomach are visualized. Surrounding vascular structures help with the localization of the pancreas ( Fig. 18.3 ).

Acute Abdominal Pain

Acute Pancreatitis

Patients with acute pancreatitis usually present with pain, vomiting, and abdominal tenderness. Laboratory findings include elevation of lipase and amylase. There are a variety of etiologies of acute pancreatitis. These are included in Table 18.1 . Probably the most common etiology is gallstones in the common bile duct. Thus the gallbladder should be scanned for any evidence of cholelithiasis. Also, careful scanning of the common bile duct may identify choledocholithiasis. Choledocholithiasis is difficult to identify and is discussed in more detail in Chapter 17 , on the gallbladder and biliary tract. Acute peripancreatic fluid collection may occur with either interstitial pancreatitis or in necrotizing pancreatitis. After 4 weeks the fluid collections in both entities have well-defined walls. In interstitial pancreatitis, the fluid collections are called pseudocysts , and in necrotizing pancreatitis, the fluid collections are called walled-off necrosis .

|

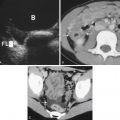

In mild acute pancreatitis, ultrasound appearance may be normal. However, subtle features can be identified with ultrasound in acute pancreatitis ( Fig. 18.4 ). One of these features is enlargement of the pancreas. This is the most common feature identified with acute pancreatitis. Unfortunately, many times there is no prior ultrasound for comparison, and thus enlargement of the pancreas, unless it is focal, may be difficult to detect. The measurement of the anterior/posterior dimension of the pancreas varies between patients and location in the pancreas. Usually, the anterior/posterior measurement of the head is <3 cm, the body is <2.5 cm, and the tail is <2.0 cm. Usually, the enlargement is diffuse, but it may be focal. If focal, it often occurs in the head of the pancreas. This focal enlargement from pancreatitis may be difficult to differentiate from a pancreatic mass, such as pancreatic cancer.

The second finding of acute pancreatitis is decreased gland echogenicity. However, this is not always present. With acute pancreatitis, the pancreas appears hypoechoic or may have hypoechoic regions. Finally, the margins of the pancreas may be poorly defined. There can also be surrounding fluid collections. Fig. 18.4 shows a case of a patient who had a prior scan when there was no evidence of pancreatitis, followed by a scan when the patient had acute pancreatitis. In this case of acute pancreatitis, there are subtle findings of slightly decreased echogenicity and slightly increased thickness of the pancreas. There are also ill-defined pancreatic margins in this case. Fluid collections may appear in different areas around the pancreas with acute pancreatitis. If seen, they may be helpful to confirm the diagnosis. Approximately 40% of patients with acute pancreatitis develop fluid collections. In acute interstitial pancreatitis, these fluid collections are homogeneous in terms of fluid density, whereas in acute necrotizing pancreatitis, these fluid collections are heterogeneous on ultrasound.

Subacute Pancreatitis (Pseudocysts)

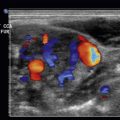

Fluid collections occurring with interstitial pancreatitis that become encapsulated after 4 weeks from the onset of symptoms are called pseudocysts . Pseudocysts require this time to mature to a point where they can be drained surgically. Pseudocysts may be very small and seen as a cystic mass in or about the pancreas. If there is no other prior imaging, small pseudocysts and cystic tumors of the pancreas may have a very similar appearance ( ![]() ). Larger pseudocysts may develop after pancreatitis. These pseudocysts are encapsulated and anechoic with good through-transmission ( Fig. 18.5 ). These are fairly easy to diagnose, as there usually has been an antecedent more-pronounced case of acute pancreatitis with resultant surrounding fluid collections that eventually develop into pseudocysts. These patients may present with pain or discomfort.

). Larger pseudocysts may develop after pancreatitis. These pseudocysts are encapsulated and anechoic with good through-transmission ( Fig. 18.5 ). These are fairly easy to diagnose, as there usually has been an antecedent more-pronounced case of acute pancreatitis with resultant surrounding fluid collections that eventually develop into pseudocysts. These patients may present with pain or discomfort.