CHAPTER 14 Pancreas

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Neuroendocrine Tumor (Islet Cell Tumor)

Symptomatic nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumors tend to be large at presentation, because patients have symptoms of mass effect rather than clinical sequelae of excess hormone secretion. The various functional neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas are listed in Table 14-1 with their associated clinical manifestations.

Table 14-1 Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

| Tumor | Hormone | Manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| Insulinoma | Insulin | Related to hypoglycemia or neuroglycopenia* |

| Glucagonoma | Glucagon | Necrolytic migratory erythema,† glucose intolerance |

| Gastrinoma | Gastrin | Peptic ulcer disease (Zollinger–Ellison syndrome) |

| VIPoma | Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide | Watery diarrhea, hypokalemia (WDHA syndrome) |

| Somatostatinoma | Somatostatin | Mild diabetes, diarrhea, steatorrhea |

| GRFoma | Growth hormone–releasing factor | Acromegaly |

| PPoma | Pancreatic polypeptide | No known typical clinical manifestations |

* Headache, light-headedness, confusion, abnormal behavior, seizures.

† Dermatitis that begins in groin and spreads to thighs, buttocks, and extremities.

ANATOMY AND NORMAL IMAGING APPEARANCE

The Normal Pancreas

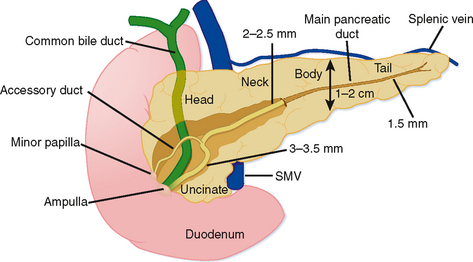

Grossly, the pancreas is a lobulated extraperitoneal organ that resides in the anterior pararenal space. As such, it is surrounded by areolar tissue and lacks a distinct capsule. The pancreas is divided into the head and uncinate process, the neck, the body, and tail (Fig. 14-1). The divisions between these portions represent arbitrary boundaries that aid in communicating the location of abnormalities. These divisions do not separate anatomically or functionally distinct units.

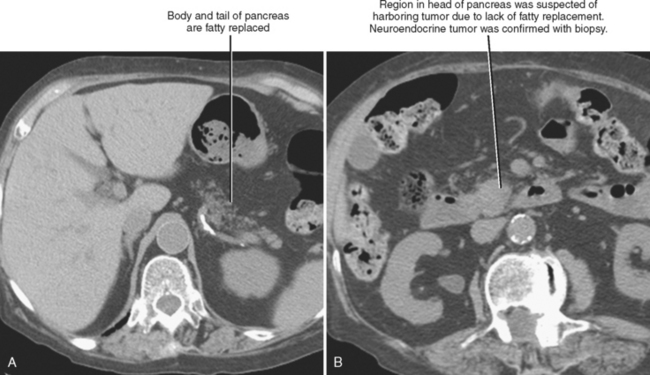

The superior mesenteric vein (SMV) serves as a useful anatomic landmark. The pancreatic head is generally considered the portion of pancreas to the right of the SMV and resides within the c-loop of the duodenum. The uncinate process is the continuation of the head posterior to the SMV and normally has a triangular shape. The posteromedial border of the uncinate process should be concave or flat rather than rounded. The portion of pancreas immediately ventral to the SMV is considered the neck, whereas the body and tail continue to the left. No clear external landmark divides body and tail of the pancreas; therefore, most radiologists roughly divide the pancreas to the left of the SMV in half, designating the more midline portion the body. The pancreatic tail lies within the splenorenal ligament, which provides a conduit for tumor and inflammation between the pancreatic tail and the spleen. The exocrine pancreas generally diminishes with age, often becoming replaced by fat.

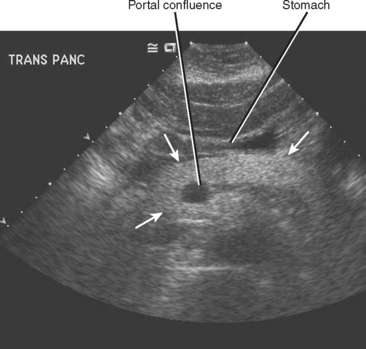

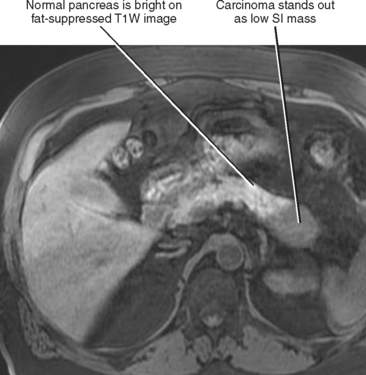

The normal pancreatic echotexture is homogeneous and isoechoic to mildly hyperechoic compared with the normal liver on ultrasound (US) images (Fig. 14-2). Increased echogenicity of the pancreas occurs with fatty infiltration. The normal pancreatic parenchyma measures 40 to 50 HU on unenhanced computed tomographic (CT) images. The pancreas is higher in signal intensity than liver, spleen, or skeletal muscle on T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images. The innately high signal intensity of the pancreas on fat-suppressed T1-weighted images makes such images valuable for detecting tumors (Fig. 14-3). The normal pancreas is only slightly higher in signal intensity than muscle on T2-weighted images. With CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), maximum pancreatic parenchymal enhancement occurs at 35 to 45 seconds after intravenous contrast administration or approximately 15 seconds after the contrast bolus arrives in the abdominal aorta.

Pancreatic Duct Anatomy

The main pancreatic duct forms when the dorsal pancreatic duct and ventral pancreatic duct join during embryologic fusion of the dorsal and ventral pancreas. The main duct (duct of Wirsung) runs the length of the pancreas and receives small branch duct tributaries at right angles along its entire length. Until recently, the normal branch ducts were rarely visible on cross-sectional imaging studies. Although this is changing with higher resolution CT scanning and MRI, numerous conspicuous branch ducts should be considered an abnormal finding on cross-sectional imaging studies. The main pancreatic duct gradually tapers from pancreatic head toward the tail without abrupt changes in caliber. The course of the main pancreatic duct varies in the region of the pancreatic neck and head. Some of the more common variants in duct course include a gradual caudal bend toward the ampulla, a “hockey-stick” configuration, a sigmoid or S-shaped course, and a looped appearance. These meanderings of the pancreatic duct are rarely important provided the duct maintains a smoothly tapering and nondilated appearance. The main pancreatic duct normally enters the duodenum with the common bile duct via the major papilla. In many individuals, the dorsal pancreatic duct persists as a smaller caliber accessory duct that extends from the main pancreatic duct near the neck of the pancreas to enter the duodenum at the minor papilla approximately 2 cm proximal to the major papilla (see Fig. 14-1). With state-of-the-art equipment, the normal accessory pancreatic duct can be routinely identified on multidetector CT and high-resolution MRI examinations (this duct is also referred to as the duct of Santorini). Usually, the accessory duct appears as a small rudimentary structure with CT and MRI, although it can be dominant in a small percentage of individuals. On secretin-stimulated MRCP examinations, the pancreatic ducts begin to enlarge approximately 1 minute after secretin administration and reach maximum diameter after approximately 20 minutes.

Vascular Anatomy of the Pancreas and Peripancreatic Vessels

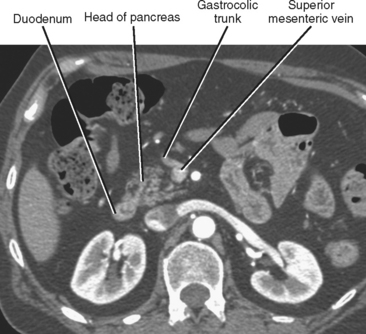

The veins draining the head of the pancreas initially course with the arteries but eventually deviate from these paths. The posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein drains to the main portal vein, and the anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein drains to the gastrocolic trunk, which drains into the SMV ventrally at the level of the midpancreatic head. The gastrocolic trunk is formed by the junction of the right gastroepiploic vein and the right or middle colic vein. The inferior pancreaticoduodenal vein drains into the proximal jejunal vein that drains into the SMV dorsally at the level of the uncinate process. The pancreaticoduodenal venous arcades serve as a potential portoportal collateral pathway in the event of portal vein obstruction. Enlargement of the pancreaticoduodenal veins in the setting of pancreatic carcinoma is a secondary sign of portal vein compromise by tumor (Fig. 14-4).

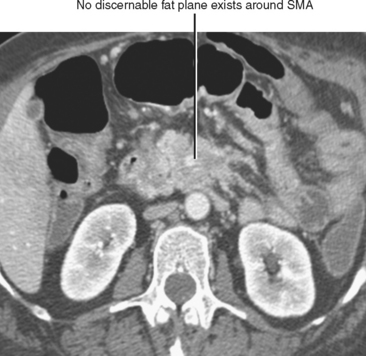

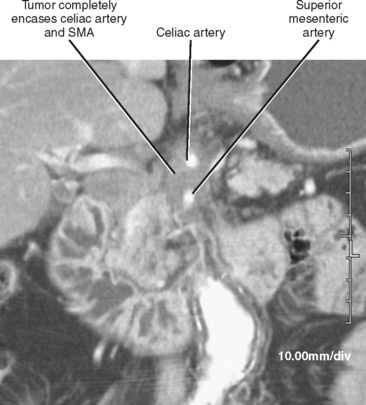

The pancreatic blood supply and drainage are identifiable on vascular-phase, thin-slice, axial CT images. The SMA and SMV normally lie to the left of the pancreatic head. A fat plane surrounds the artery, whereas a fat plane is only occasionally visible between the right lateral margin of the SMV and the pancreatic head. The GDA is easily identified on imaging studies coursing along the right anterolateral border of the pancreatic head. The anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery continues caudally from the GDA along the anterolateral pancreatic head. The anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein usually drains into the gastrocolic trunk or right gastroepiploic vein and tends to be horizontally oriented on axial CT and MR images. The gastrocolic trunk is easily and consistently found on cross-sectional imaging studies just anterior to the midpancreatic head (Fig. 14-5). The posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery (first branch of the GDA) and vein are seen in the region of the distal bile duct between the pancreatic head and the proximal duodenum. The vein can often be seen in cross section on axial images and drains into the suprapancreatic portion of the portal vein within 2 cm of the portal confluence. The inferior pancreaticoduodenal vessels may be visible at the level of the uncinate process, although their small size makes them difficult to identify definitively.

Figure 14-5 Enhanced axial computed tomographic image through the abdomen demonstrates the gastrocolic trunk.

Developmental Anomalies of the Pancreas

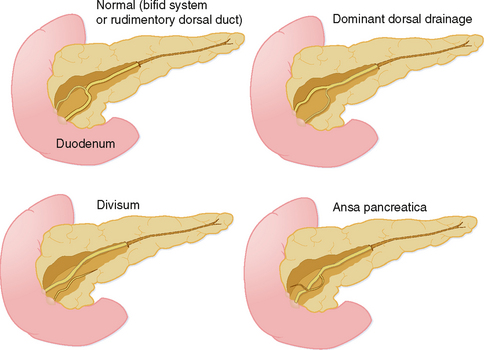

The organogenesis of the pancreas occurs in concert with the formation of the liver and duodenum, and involves two separate components, dorsal and ventral, each with its own ductal system. During development, the ventral pancreas rotates posterior to the duodenum to join with the dorsal pancreas, forming a single organ. The two ductal systems also join to create the main pancreatic duct. Not surprising, given the complexity of this process, pancreatic variant anatomy is relatively common (Fig. 14-6).

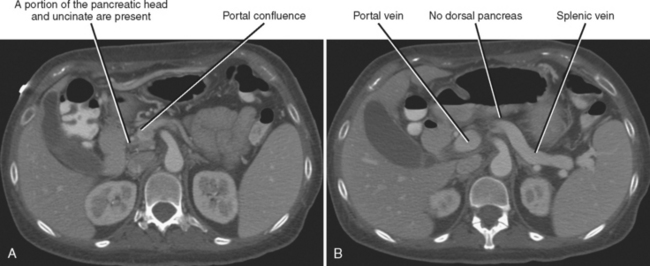

Agenesis of the dorsal anlage (dorsal agenesis) occurs when only the pancreatic head and uncinate process develop, and the accessory duct (Santorini) is absent (Fig. 14-7). Dorsal agenesis may be incomplete, resulting in the presence of a variable portion of the dorsal pancreas and accessory duct. Dorsal agenesis can be associated with polysplenia.

Ectopic pancreatic tissue can be present within organs of entodermal origin (organs arising from the primitive gut). The gastric antrum and proximal duodenum are most commonly affected. In such cases, the ectopic tissue can consist of acinar cells, islet cells, and a small duct. Ectopic pancreas can also occur in other organs such as the remainder of the small bowel, colon, appendix, Meckel’s diverticulum, gallbladder, liver, and spleen. Rarely, ectopic pancreas occurs above the diaphragm. Abnormalities that affect the pancreas, such as neoplasia and inflammation, can also affect heterotopic pancreatic tissue.

Pancreas divisum is a relatively common anomaly (almost 10% of individuals) characterized by completely separate dorsal and ventral ductal systems draining the pancreas (Fig. 14-8). In divisum, the dorsal duct drains the body and tail of the pancreas via the minor papilla, whereas the ventral pancreatic duct drains the caudad portion of the head and uncinate process via the major papilla. This variant has been implicated in the development of pancreatitis, although many cases of pancreas divisum are discovered incidentally on high-resolution CT or MR images. Occasionally, the dorsal and ventral moieties are separated by a fat plane, but frequently the pancreas is normal in size and shape.

Ansa pancreatica occurs when the normal communication between the accessory pancreatic duct and ventral (main) duct is replaced by a looping branch duct that courses from the region of the minor papilla to drain into the main pancreatic duct (see Fig. 14-6).

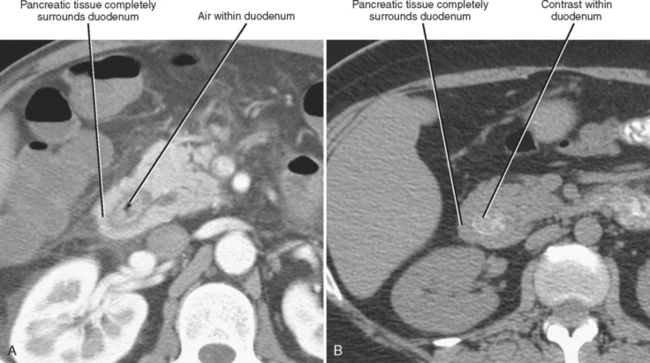

Annular pancreas is much less common than divisum. In the case of annular pancreas, the duodenum is completely encircled by pancreatic tissue. Pancreatic ducts can either encircle or drain directly into the duodenum. This anomaly manifests on upper gastrointestinal series in neonates as obstructive narrowing of the second portion of the duodenum. Occasionally, annular pancreas presents in adulthood as an incidental finding on CT or MRI (Fig. 14-9). The pancreatic tissue surrounding the descending duodenum maintains identical echogenicity, attenuation, signal intensity, and enhancement characteristics to the remainder of the pancreas. When the duodenum is not adequately distended with oral contrast material or fluid, the combination of collapsed duodenum and annular pancreas may simulate a neoplasm of the pancreatic head.

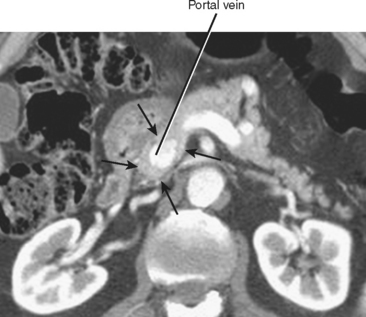

One final pancreatic variant rarely described in the literature involves complete encasement of the portal vein by pancreatic tissue (Fig. 14-10). In such cases, pancreatic parenchyma surrounds the portal vein on all sides, potentially simulating a mass lesion or encasement of the portal vein by tumor. The main pancreatic duct can course anterior or posterior to the portal vein in such cases. Surgical resection of the pancreas can be potentially complicated by this variant.

PANCREATITIS

Acute Pancreatitis

Imaging Findings of Acute Pancreatitis

RADIOGRAPHY

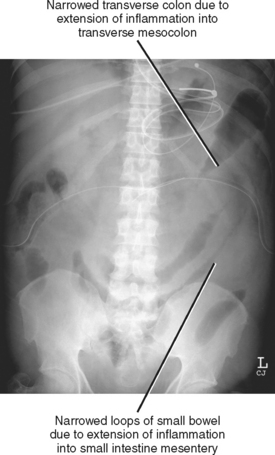

Conventional radiographs are not able to directly image pancreatic inflammation and rarely yield a specific diagnosis of pancreatitis. However, radiographs are often abnormal in the setting of acute pancreatitis (Fig. 14-11). The most common radiographic abnormalities include a focal or generalized ileus, pleural effusion (often left sided), and basal atelectasis. The “colon cutoff sign” originally referred to gaseous distention of the right colon with abrupt termination of the gas column to the left of the hepatic flexure. This sign has been generalized to include areas of narrowing anywhere in the colon related to mesocolic involvement with pancreatitis. Dilatation of the descending duodenum (“sentinel-loop”) can be a sign of pancreatic inflammation and is more suggestive of acute pancreatitis when accompanied by colonic involvement.

BARIUM

Pancreatic inflammation can extend within the small-intestine mesentery, causing thickening of the small-bowel mucosal folds. These findings can extend to the cecum via the ileocolic mesentery.

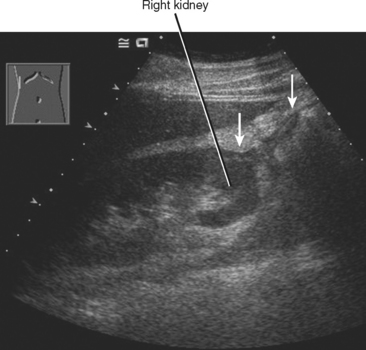

ULTRASOUND

Diffuse acute pancreatitis manifests on US as decreased or heterogeneous echogenicity of the pancreas, which can appear enlarged. In the setting of pancreatitis, US has its greatest utility in the diagnosis of gallstones, choledocholithiasis, and biliary obstruction. Hypoechoic inflammation, acute fluid collections, and pseudocysts are easily revealed provided a suitable sonographic window exists (Fig. 14-12). Lesser sac collections are relatively easy to see anterior to the pancreas. Fluid accumulating in the superior recess of the lesser sac can be seen around the caudate lobe. Standard grayscale US is relatively insensitive for the diagnosis of pancreatic necrosis in the setting of acute pancreatitis. Table 14-2 lists some sonographic signs of acute pancreatitis.

Table 14-2 Sonographic Abnormalities in Acute Pancreatitis

| Finding | Prevalence Rate |

|---|---|

| Peripancreatic inflammation | 60% |

| Heterogeneous parenchyma | 56% |

| Decreased gland echogenicity | 44% |

| Indistinct ventral margin | 33% |

| Glandular enlargement | 27% |

| Focal parenchymal echo change | 23% |

| Peripancreatic fluid collection | 21% |

| Focal mass (usually hypoechoic) | 17% |

| Perivascular inflammation | 10% |

| Pancreatic duct dilatation | 4% |

| Venous thrombosis | 4% |

Adapted from Finstad TA, Tchelepi H, Ralls PW: Sonography of acute pancre-atitis: prevalence of findings and pictorial essay, Ultrasound Q 21:95-104, 2005, by permission.

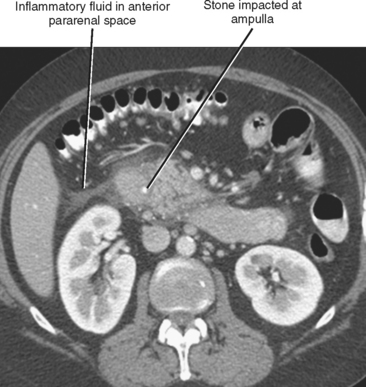

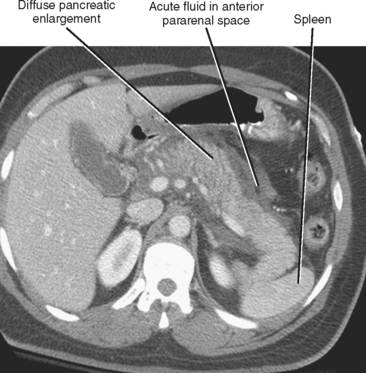

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

The initial diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is based on clinical and laboratory findings. However, pancreatitis occasionally presents with a confusing clinical picture. In such cases, CT findings can suggest the correct diagnosis. Furthermore, enhanced CT is of benefit in the initial evaluation of pancreatitis to assess its severity and to identify complications. Intravenous contrast media improve detection of pancreatic necrosis or complications such as pseudoaneurysm formation or venous thrombosis. Occasionally, CT will establish a cause for pancreatitis such as choledocholithiasis or aberrant pancreatic ductal anatomy (Fig. 14-13).

The CT findings of uncomplicated acute pancreatitis include focal or diffuse pancreatic enlargement with infiltration or stranding in the peripancreatic fat (Fig. 14-14). Peripancreatic fluid collections commonly occur and either resolve over time or organize to form pseudocysts. After administration of intravenous contrast material, the inflamed pancreas can enhance heterogeneously. Confluent areas of nonenhancing tissue suggest pancreatic necrosis.

Intraabdominal Spread of Acute Pancreatitis

Pathways for spread of pancreatitis in the lower abdomen are within the transverse mesocolon to the transverse colon, and within the small intestine mesentery to the small bowel and right lower quadrant. Pancreatic inflammation can also extend caudally via the infrarenal space (confluence of the pararenal spaces beneath the kidneys) or the small-intestine mesentery into the pelvis. Extension along the left lateral pelvis can continue into the sigmoid mesocolon to the sigmoid colon. Inflammation can also extend from the pelvic sidewalls via the broad ligaments to the uterus and ovaries or posteriorly to the presacral space and mesorectum.

Complications of Acute Pancreatitis

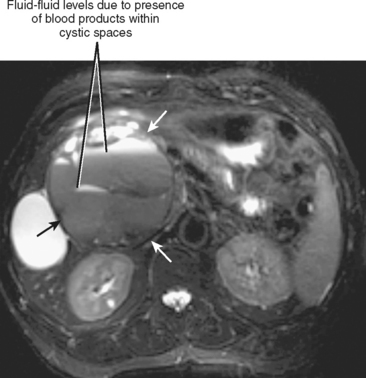

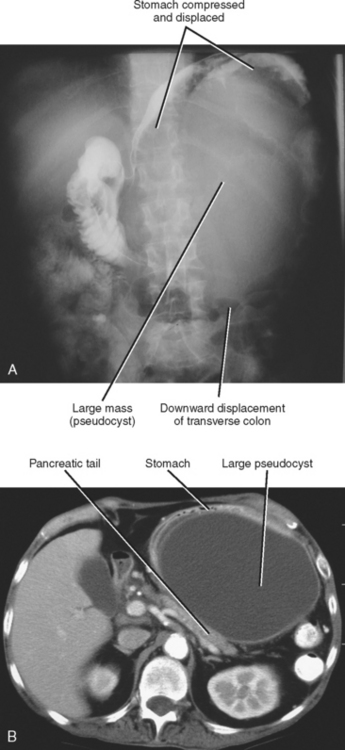

Imaging plays an important role in the detection and management of complications related to pancreatitis. Pancreatic pseudocysts are collections of inflammatory fluid contained within a fibrous capsule (Fig. 14-15). Pseudocysts result from the maturation of acute peripancreatic fluid collections that fail to resolve over the course of several weeks. Many pseudocysts maintain a communication with the pancreatic duct, and this communication may be evident on thin-section CT or MRCP images. Pseudocysts that become symptomatic because of mass effect or infection are usually managed by percutaneous or endoscopic drainage. Pancreatic pseudocysts can exert mass effect on the posterior gastric wall visible with radiography or fluoroscopy (Fig. 14-16). The distinction between pseudocysts and other cystic pancreatic masses is discussed later in this chapter.

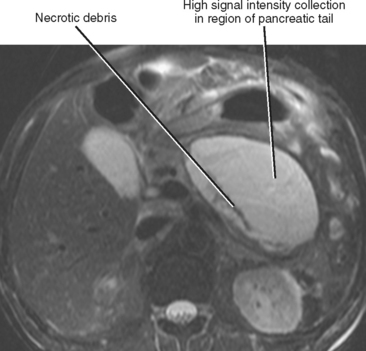

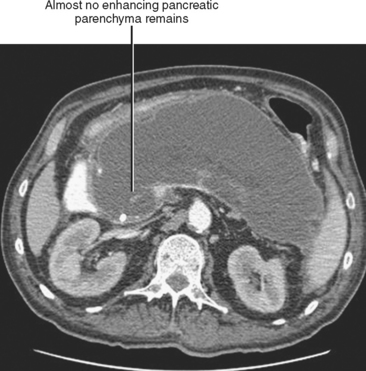

Pancreatic necrosis is present when one or more demarcated foci of pancreatic parenchyma fail to enhance on dynamic contrast-enhanced CT or MRI (≤30 HU at peak enhancement with CT) and occurs in up to a third of cases of acute pancreatitis (Fig. 14-17). Pancreatic necrosis increases mortality and may require necrosectomy when extensive. Focal acute fluid collections, fatty infiltration, or glandular atrophy should not be misinterpreted as pancreatic necrosis. Pancreatic necrosis can become infected, usually several weeks after onset of acute pancreatitis. Gas within an area of nonenhancing parenchyma suggests the diagnosis, although gas also results from fistulous communication with the bowel or prior intervention. Unlike pancreatic pseudocyst or abscess, sterile or infected pancreatic necrosis is difficult to manage via catheter drainage because of the presence of copious solid debris.

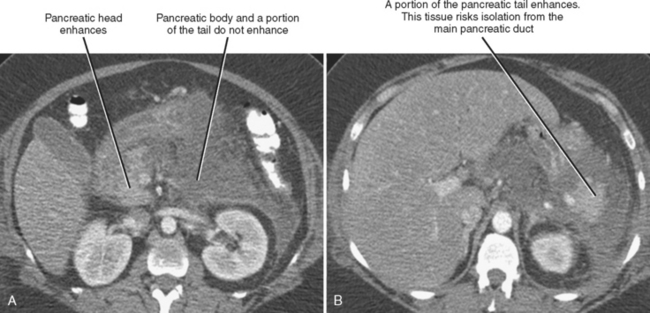

Pancreatic necrosis can involve the central portion of the pancreas, potentially resulting in interruption of the pancreatic duct because of necrosis of the duct epithelium (Fig. 14-18). In such cases, a variable amount of the pancreatic tissue proximal to the area of necrosis becomes isolated from the main ductal system. This potentially allows leakage of pancreatic secretions into the peripancreatic spaces. The imaging findings of a disconnected pancreatic duct include necrosis of at least 2 cm of pancreas, viable pancreatic tissue proximal to the disruption, and extravasation of contrast material injected at pancreatography. On CT and MR images, a large intrapancreatic fluid collection is often present in the setting of disconnected pancreatic duct, although this finding is nonspecific, because disruption of a pancreatic branch duct can also cause an intrapancreatic fluid collection. Although a branch duct disruption can often be treated with placement of a pancreatic stent, main duct disconnection often requires surgery.

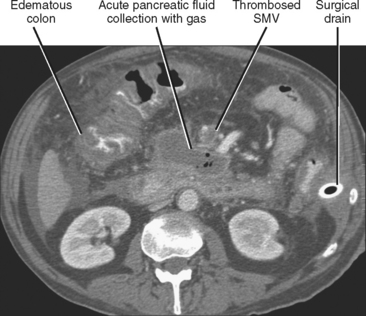

Venous thrombosis is relatively common in the setting of pancreatitis and most often involves the splenic vein because of its close relation with the pancreas. Splenic vein thrombosis should be suspected when the vein fails to enhance on CT or MR images after intravenous contrast administration, or when the vein fails to demonstrate flow with Doppler interrogation. Enlarged gastroepiploic veins often signify collateral flow in the setting of splenic vein thrombosis. Other veins to evaluate for evidence of thrombosis in the setting of pancreatitis include the superior mesenteric and portal veins (Fig. 14-19).

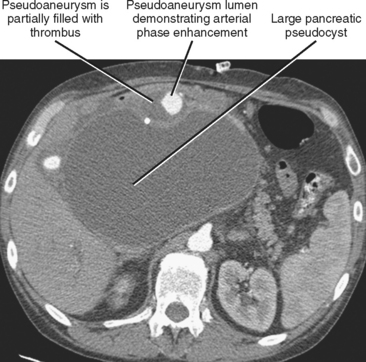

Pseudoaneurysm formation results from weakening of an arterial wall by pancreatic enzymes. Pseudoaneurysms are typically round and demonstrate arterial-phase enhancement on CT and MRI (Fig. 14-20). Depending on the timing of the scan, some pseudoaneurysms may not completely fill until the second contrast-enhanced phase of a dynamic study; therefore, all vascular phases should be routinely consulted. Pseudoaneurysms will demonstrate evidence of flow on color Doppler images. Whenever a round, potentially fluid-filled structure is identified in the region of the pancreas in a patient with acute pancreatitis, one must always consider the possibility of pseudoaneurysm before attempting aspiration or drainage. Table 14-3 lists some additional potential complications resulting from pancreatitis.