PARATHYROID GLANDS: HYPERPARATHYROIDISM

KEY POINTS

- Imaging with anatomic and physiologic techniques is very useful in the preoperative localization of parathyroid adenoma, especially given newer surgical approaches to the treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism.

- Imaging protocols must be inclusive of all sites of possible ectopic adenoma.

Parathyroid developmental conditions are discussed in Chapter 153. Beyond those conditions, the parathyroid gland disease of primary interest with regard to diagnostic imaging is hyperparathyroidism. This condition may be primary, due to an autonomously functioning adenoma or rarely a carcinoma. Hyperparathyroidism may also be secondary, due to glandular hyperplasia driven by the physiologic state of calcium and phosphorous metabolism that accompanies chronic renal insufficiency. Autonomous adenomas may coexist with glandular hyperplasia in the secondary disease. In head and neck imaging, primary hyperparathyroidism is the condition of main interest related to the desire for preoperative localization of the responsible adenoma.

The modern history of preoperative localization of parathyroid adenoma dates to the late 1970s with seminal work by Fred Sample at the University of California–Los Angeles using the then-new modality of gray-scale ultrasound for localization (Fig. 174.1A,B). This was followed promptly by technetium thallium subtraction radionuclide localization. For a time, venous sampling for parathormone levels was used in difficult cases as well as aspiration of a suspected adenoma with assay for parathormone. There has been a period of interest in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a localizing tool since the earlier computed tomography (CT) units were somewhat limited in accuracy, especially in the setting of recurrent disease. The bias for anatomic imaging is now shifting to a combination of volumetric multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and ultrasound.

The utility of and justification for localization was questioned for nearly two decades dating from the late 1970s; however, with the current maturation of more focused surgical approaches, localization is now considered a critical step in the decision-making path for many patients with established primary hyperparathyroidism. The current approach to localization uses a combination of ultrasound, updated MDCT, and radionuclide studies.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Embryology

The developmental pathway of the branchial apparatus that explains the position of ectopic glandular tissue is presented in Chapter 153 and reviewed again with more focus on the thyroid and parathyroid glands in Chapter 169. It is important to consider this developmental pathway in designing strategies for parathyroid adenoma localization. Essentially, parathyroid tissues, and therefore parathyroid adenomas, can be found from the carotid bifurcation to the lowermost positions of thymic migration in the mediastinum. With that knowledge, it is clear that ultrasound, radionuclide studies, and MRI cannot comprehensively identify all adenomas anatomically, and each has technical limitations in this regard. However, since the vast majority of adenomas are in the neck, reasonable, safe, and cost-effective approaches to preoperative localization can be developed based on this core knowledge.

Applied Anatomy

The key anatomy of the thyroid gland and surrounding structures in the region as seen on all imaging modalities that must be understood to adequately identify an adenoma and/or hyperplastic, parathyroid glands includes the thyroid gland, the longus colli muscle, the tracheoesophageal groove, inferior and superior thyroid neurovascular bundles, the carotid sheath to the bifurcation, and the anterior mediastinum. It is essential to understand the differences in how lymph nodes in all of these areas vary in position, appearance, and enhancement characteristics.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

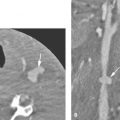

The search for parathyroid adenomas requires a more customized approach than that used in the general evaluation of the infrahyoid neck with CT and MRI. Specific protocols for such imaging are presented in Appendixes A and B. The essential elements are to be sure the protocol covers the neck from the carotid bifurcation to include the entire anterior mediastinum with sufficiently thin sections. With MDCT, a suitable volume set of such data is simply accomplished with a three-phase computed tomographic angiography (CTA) allowing for up to a four-dimensional assessment of the anatomy and pathology of interest.

Ultrasound is valuable for parathyroid localization. The technique requires an understanding of a proper search pattern of the anatomic zone visible between the longus colli muscle and back surface of the thyroid gland.

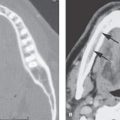

FIGURE 174.1. Ultrasound and technetium sestamibi images of patients with parathyroid adenomas. A: Patient 1. A study done in the late 1970s at the University of California–Los Angeles showing an unusually large adenoma with cystic components. Concern was for parathyroid carcinoma based on the size and unusual necrotic features. A benign adenoma was removed. B: Patient 2. Ultrasound showing a nodule with its typical location relative to the longus colli muscle and thyroid gland as seen in this sagittal image. Adenomas are typically of relatively low echogenicity compared to the normal thyroid texture. C–F: Patient 3. Ultrasound imaging showing a parathyroid adenoma with slightly more echogenicity relative to the normal thyroid gland texture than usual in the axial (C) and less so in the sagittal (D) planes (arrows). In (E) and (F), the technetium sestamibi study with the immediate scan seems to confirm a parathyroid adenoma (arrow); however, the washout scan in (F) shows no residual activity. Despite this, the patient underwent surgery, and a parathyroid adenoma was removed.

FIGURE 174.2. Ultrasound of a patient with intrathyroidal parathyroid adenomas seen in the axial image in (A) and sagittal image in (B).

The approach with radionuclide has essentially evolved to technetium-labeled sestamibi as discussed in Chapter 5.

Pros and Cons

Ultrasound is an excellent starting point for evaluating adenomas that are in the normal parathyroid gland positions. Many ectopic adenomas inferior to the gland but not in the mediastinum can be localized with ultrasound (Figs. 174.1–174.3). Upper pole adenomas are less reliably localized by ultrasound when ectopic (Fig. 174.1). Mediastinal adenomas cannot be studied.

MRI has weaknesses related to motion artifact in evaluating the chest. It is also liable to motion artifact at the cervicothoracic junction. The section thickness used approaches the size of some adenomas, making it possible to miss small adenomas due to volume averaging. Fat suppression at the thoracic inlet can be variable; therefore, contrast-enhanced studied may result in masking lesions in fat when fat suppression is unsuccessful. In general, MRI is a marginally useful test for this indication given the excellent results possible with a logical progression from ultrasound to radionuclide studies and then CT for problem solving. MRI may be used in patients who cannot have iodinated contrast.

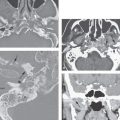

FIGURE 174.3. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance (MR) of a parathyroid adenoma. A, B: Ultrasound showing the adenoma to be very similar in echogenicity to the thyroid gland as seen in the axial section (arrow). In (B), the adenoma is of more obvious diminished echogenicity relative to the thyroid texture (arrow). C: Further confirmation was desired, so an MR study was done. The study confirmed a parathyroid adenoma on this contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image showing the adenoma to enhance somewhat.

FIGURE 174.4. A patient with primary hyperparathyroidism, with radionuclide study and ultrasound failing to localize the adenoma. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) study was done in the days prior to multidetector CT scans. This study shows the adenoma in an almost retroesophageal position (arrow), likely explaining the difficulty of localizing the adenoma on ultrasound. Note that the adenoma is medial to the traditional landmarks of the longus colli muscle and thyroid gland that are used as localizing anatomic features on ultrasound. The small size of the adenoma probably accounts for the lack of radionuclide localization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree