Hyperparathyroidism represents by a varied spectrum of presentations, from those individuals who have overt symptoms directly attributable to hypercalcemia to those who are asymptomatic at diagnosis. Indications for surgical intervention in the asymptomatic population have changed as the long-term experience with these patients has grown. Use of additional imaging techniques to aid localization and a detailed understanding of the anatomy can be critical to a successful operative outcome. This article discusses the pertinent issues that surround the current surgical management of parathyroid disease with a focus on epidemiology, surgical anatomy, and operative strategies.

Hyperparathyroidism represents by a varied spectrum of presentations, from those individuals who have overt symptoms directly attributable to hypercalcemia to those who are asymptomatic at diagnosis. Indications for surgical intervention in the asymptomatic population have changed as the long-term experience with these patients has grown. Over the last 10 years, surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism, in the setting of a single localized adenoma, has evolved for some surgeons from a standard four-gland exploration into a radio-guided, minimally invasive outpatient procedure. Additionally, technological developments, such as the rapid intraoperative assessment of parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels, can be used to guide the effectiveness of a surgical procedure while the patient remains under anesthesia. Medications such as calcimimetics, agents that reduce the PTH secretion, may have a role in the treatment of selected cases of hyperparathyroidism. Despite the progress made in the technology associated with the surgical management of this diagnosis, however, patients requiring reoperation for persistent hypercalcemia continue to remain a challenge for even the most experienced surgeons. Use of additional imaging techniques to aid localization and a detailed understanding of the anatomy can be critical to a successful operative outcome. This article discusses the pertinent issues that surround the current surgical management of parathyroid disease with a focus on epidemiology, surgical anatomy, and operative strategies.

Epidemiology

PTH acts to increase serum calcium levels by working at the level of the bone, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract. Hyperparathyroidism reflects the adjustment of the body’s set point for serum calcium at a level above normal. The calcium-sensing receptor (CaR) of the parathyroid gland is the principal regulator of PTH secretion. Activation of this receptor, with changes in serum calcium levels, also affects calcitonin secretion and urinary calcium secretion.

Hyperparathyroidism presents in three forms: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary hyperparathyroidism is characterized by hypercalcemia in the setting of an elevated PTH level. The estimated prevalence of primary hyperparathyroidism in North America is 1 in 1000 patients and the highest incidence is in postmenopausal women. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is seen in association with longstanding renal failure and treatment focuses on medical management with a subset of patients ultimately requiring surgery. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism occurs in the setting of secondary hyperparathyroidism when the parathyroid glands lose the ability for feedback regulation.

Primary hyperparathyroidism is more common in females (3:1 ratio) and represents a single adenoma in greater than four fifths of all cases. Most patients are asymptomatic at presentation and are ultimately diagnosed when a serum calcium level is assessed for other reasons. The typical age of presentation is during the fifth and sixth decades of life. A history of long-term lithium use may be associated with the development of primary hyperparathyroidism.

Embryology and basics

The parathyroid glands are derived from the third (inferior glands associated with the thymus) and fourth (superior glands) branchial pouches; this is pertinent to surgical management of the glands and the assessment for missing parathyroid adenomas.

The typical parathyroid gland weighs between 30 and 65 mg and is oval with a mahogany-tan color. It is composed of chief (producing PTH), intermediate, and oxyphilic cells. The vast majority of parathyroid adenomas are the result of expansion of the chief cell population; however, a limited percentage of adenomas represent oncocytic and lipoadenomatous variants. Four glands are normally present in 84% of patients. Three percent of patients are reported to have only three glands and as many as 13% of patients have been noted to have more than four glands.

The typical location of the superior parathyroid glands is 1 cm superior to the junction of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) and inferior thyroid artery. The inferior glands, which are more variable in anatomic localization, approximate the inferolateral or posterior thyroid pole in 50% of cases and are within the thyrothymic fat in 24% of cases.

In a review of more than 20,000 cases of hyperparathyroidism from 1995 to 2003 performed by Ruda and colleagues the reported frequency of specific pathologies was the following: solitary adenoma, 88.90%; double adenoma, 4.14%; multiple gland hyperplasia disease, 5.74%; parathyroid carcinoma, 0.74%.

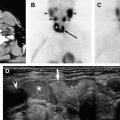

Ectopic locations where aberrant parathyroid glands can be located include: para/retroesophageal region, intrathyroidal (more commonly superior), carotid sheath (more commonly inferior), associated with the thymus, and mediastinal.

Patients who have parathyroid carcinoma calcium tend to present with calcium levels greater than 14 mg/dL with 80% of patients being symptomatic from the hypercalcemia at diagnosis. Based on the 22-year review at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, there was noted to be a slight male predominance with the mean age of presentation 47 years. Most patients initially presented with locally invasive disease without distant metastasis. Locoregional recurrence was common and all deaths were considered related to hypercalcemia.

Assessment for variants of the multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes may require evaluation in the hypercalcemic population. These variants include MEN1 (parathyroid hyperplasia, pituitary adenoma, and pancreatic cell tumors), MEN2A (parathyroid hyperplasia, MTC, pheochromocytoma), non-MEN familial hyperparathyroidism, and benign familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (BFHH). In BFHH, a defect in PTH sensing in renal tubules within the kidney results in hypercalcemia.

Embryology and basics

The parathyroid glands are derived from the third (inferior glands associated with the thymus) and fourth (superior glands) branchial pouches; this is pertinent to surgical management of the glands and the assessment for missing parathyroid adenomas.

The typical parathyroid gland weighs between 30 and 65 mg and is oval with a mahogany-tan color. It is composed of chief (producing PTH), intermediate, and oxyphilic cells. The vast majority of parathyroid adenomas are the result of expansion of the chief cell population; however, a limited percentage of adenomas represent oncocytic and lipoadenomatous variants. Four glands are normally present in 84% of patients. Three percent of patients are reported to have only three glands and as many as 13% of patients have been noted to have more than four glands.

The typical location of the superior parathyroid glands is 1 cm superior to the junction of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) and inferior thyroid artery. The inferior glands, which are more variable in anatomic localization, approximate the inferolateral or posterior thyroid pole in 50% of cases and are within the thyrothymic fat in 24% of cases.

In a review of more than 20,000 cases of hyperparathyroidism from 1995 to 2003 performed by Ruda and colleagues the reported frequency of specific pathologies was the following: solitary adenoma, 88.90%; double adenoma, 4.14%; multiple gland hyperplasia disease, 5.74%; parathyroid carcinoma, 0.74%.

Ectopic locations where aberrant parathyroid glands can be located include: para/retroesophageal region, intrathyroidal (more commonly superior), carotid sheath (more commonly inferior), associated with the thymus, and mediastinal.

Patients who have parathyroid carcinoma calcium tend to present with calcium levels greater than 14 mg/dL with 80% of patients being symptomatic from the hypercalcemia at diagnosis. Based on the 22-year review at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, there was noted to be a slight male predominance with the mean age of presentation 47 years. Most patients initially presented with locally invasive disease without distant metastasis. Locoregional recurrence was common and all deaths were considered related to hypercalcemia.

Assessment for variants of the multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes may require evaluation in the hypercalcemic population. These variants include MEN1 (parathyroid hyperplasia, pituitary adenoma, and pancreatic cell tumors), MEN2A (parathyroid hyperplasia, MTC, pheochromocytoma), non-MEN familial hyperparathyroidism, and benign familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (BFHH). In BFHH, a defect in PTH sensing in renal tubules within the kidney results in hypercalcemia.

Indications for surgery

Symptomatic patients are offered surgery with the goal of stabilizing or resolving the issues that lead to their initial presentation. Most hyperparathyroid patients are diagnosed when they are asymptomatic. As such, the indications for the surgical management of these patients were established. In 1990, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Conference on Asymptomatic Primary Hyperparathyroidism established guidelines indicating parameters for parathyroidectomy ( Box 1 ).

The 1990 Guidelines specifying indications for parathyroidectomy in the asymptomatic patient and the 2002 modifications to the original guidelines.

Serum calcium >12 mg/dL (or ≥1.6 mg/dL greater than the referenced upper limit of normal)

- •

2002 modification: serum calcium decreased from 1.6 mg/dL to 1.0 mg/dL above the upper limit of normal

- •

Marked hypercalciuria (24-hour urinary calcium >400 mg/d)

Overt manifestations (such as nephrolithiasis, osteitis fibrosa cystica, or classic neuromuscular disease)

Markedly reduced cortical bone density (z-score < −2)

- •

2002 modification: bone density at the lumbar spine, hip, or distal radius greater than 2.5 standard deviations below peak mass (using t-scoring instead of z-score)

- •

Reduced creatinine clearance (by greater than 30% compared with age-matched cohorts) in the absence of any other cause

Age <50 years

Patients in whom surveillance with close clinical follow-up is not possible or desired

Data from NIH Conference. Diagnosis and management of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: consensus development conference statement. Ann Intern Med 1991;114:593–7; and Bilezikian JP, Potts Jr JT, Fuleihan Gel-H, et al. Summary statement from a workshop on asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: a perspective for the 21st century. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87(12):535–61.

In 2002 the NIH Workshop on Primary Hyperparathyroidism re-examined the prior guidelines and changed many of the original recommendations. The criterion for total serum calcium concentration was decreased to 1 mg/dL (from 1.6 mg/dL) above the upper limits of normal. Bone density at the lumbar spine, hip, or distal radius greater than 2.5 standard deviations below peak bone mass was also established as an indication for parathyroidectomy. The original recommendations of intervening for 24-hour urinary calcium greater than 400 mg, for the reduction of creatinine clearance by 30% (compared with age-matched subjects), when medical surveillance is not desirable or possible, and for age less than 50 years remained unchanged. Approximately 50% of asymptomatic patients fulfill one of the previously described indications for surgery. Patients who do not have an indication for surgery, or who desire not to pursue surgical intervention, should be followed long term to assess for the development of a surgical indication or symptoms related to their diagnosis.

The role that calcimimetics will have on future indications for surgery in the asymptomatic patients is yet to be determined.

History and physical examination

In the symptomatic patient, the duration and intensity of the patient’s presenting symptoms should be reviewed. Diagnoses, such as hypertension and peptic ulcer disease, that may or may not be related to the diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism, may be noted within the patient’s history. Symptoms of fatigue, depression, memory problems, abdominal pain, constipation, and pain in other parts of the body can be associated with hypercalcemia. A history of prior low-dose irradiation is associated with an increased risk for developing hyperparathyroidism. Nephrolithiasis is the most common presentation of symptomatic disease and is noted in approximately one fifth of patients who have primary hyperparathyroidism. History of prior thiazide diuretic or lithium and prior consumption of calcium and vitamins A and D should also be assessed.

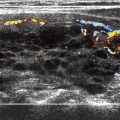

Issues of importance when assessing a patient for parathyroid surgery include a history of prior neck or thyroid-based surgery and the patient’s ability to extend the neck. The presence of coexisting thyroid pathology (nodule, goiter) could make a procedure more technically challenging and may require preoperative ultrasound assessment and fine needle aspiration. True vocal cord function and assessment of the airway allows the surgeon to appreciate the patient’s baseline vocal cord function in particular in the setting of revision parathyroid surgery. Overall the results of physical examination, as it relates to the diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism, are typically unremarkable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree