PAROTID GLAND DEVELOPMENTAL ANOMALIES

KEY POINTS

- Imaging is central to a proper diagnosis of branchial apparatus and other parotid-region anomalies.

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are the prime diagnostic imaging tools since a sinus tract cannot usually be identified or, if found, injected.

- Ultrasound is cost additive, not definitive, and should be avoided in almost all cases for these reasons.

- A cystic parotid mass in an adult should be presumed to be neoplastic or infectious rather than of branchial origin unless characteristic associated findings are identified.

Developmental abnormalities involving the parotid region are mainly those due to first branchial apparatus anomalies and venolymphatic malformations. Syndromic craniofacial anomalies may also involve the first branchial apparatus as part of a more complex developmental anomaly. Epidermoid and dermoid cysts and teratomas rarely present as strictly parotid-region masses (Fig. 176.1).

Congenital anomalies of first branchial apparatus origin affecting the parotid region come to imaging in both the pediatric and adult population. Their embryologic origin explains the diverse appearance of these anomalies on imaging studies as well as their various clinical presentations (Figs. 153.7, 153.8, and 176.2–176.4). In the parotid region, anomalous branchial apparatus development results in cysts and fistulas with occasionally associated epidermoid cysts and temporal bone anomalies (Figs. 153.7, 153.8, and 176.3). Their anatomic relationships and appearance on imaging studies predicts their embryologic origin and raises related treatment implications.

Proliferative hemangioma and venolymphatic malformations may originate in the parotid gland and spread transcompartmentally, be isolated to the parotid gland, or involve the gland secondarily (Figs. 176.5–176.8).

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Embryology and Mechanisms of First Branchial Apparatus Anomalies

The general development of the branchial apparatus is summarized in Chapter 153. The branchial apparatus has six mesodermal arches separated externally by ectodermal-lined branchial clefts or grooves and internally by endodermal-lined pharyngeal pouches1,2 (Figs. 153.1). The mesoderm of the branchial arches contributes to specific bone, cartilage, and vascular structures, and each arch is related to a specific cranial nerve (Fig. 153.4). The facial and trigeminal nerve are both related to the first arch.1

The mechanism of first branchial apparatus developmental errors is incomplete obliteration of one or more components leaving buried cell rests trapped where they do not belong during the embryologic stage, where they later produce branchial apparatus–related problems.1,2 This may produce aberrant migration and ectopias of glandular tissue and/or cysts, sinuses, and fistulas related to migrational pathways.1–3 The first branchial cleft persists as an adult structure providing the epithelium of the external auditory canal (Figs. 153.1–153.5). The first arch contributes to facial development. The first pharyngeal pouch forms part of the eustachian tube and tubotympanic recess. The parotid gland, a first pouch derivative, is an epithelial growth starting at the oral cavity and migrating toward the ear.

First branchial cleft cysts and fistulas are the most common and well-known anomalies in the parotid region. Incomplete migration of endoderm can result in a rare absence of the parotid gland. Rests of cells left in the parapharyngeal space may account for prestyloid parapharyngeal space–origin benign and malignant salivary gland tumors.

The developmental background related to proliferative hemangiomas and vascular malformations and their classifications is discussed in Chapter 8.

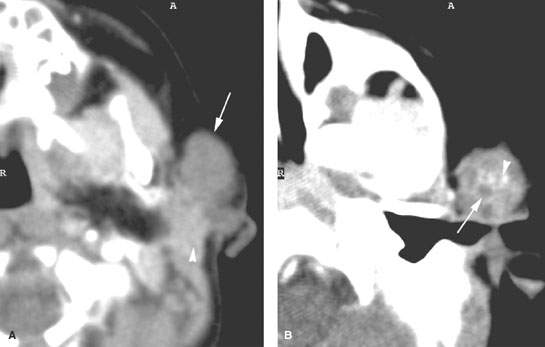

FIGURE 176.1. An infant presenting with a periparotid mass that eventually proved to be a teratoma. A computed tomography study was done. A: The mass (arrow) projects anteriorly adjacent to the normal parotid tissue (arrowhead). B: A section slightly higher shows some inhomogeneity with the mass, possibly cyst formation (arrow), and possible small calcification (arrowheads).

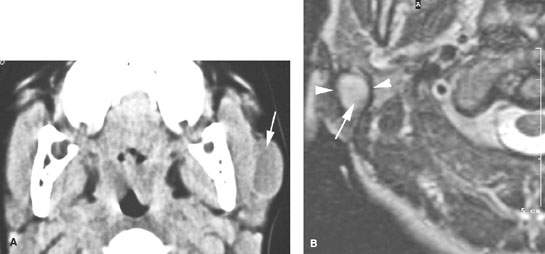

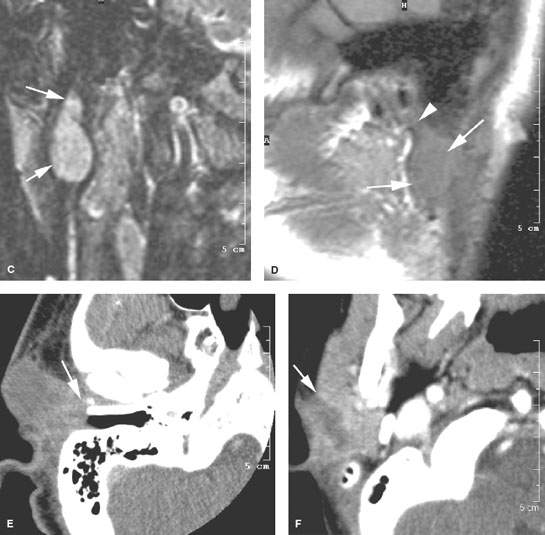

FIGURE 176.2. Four patients with first branchial apparatus abnormalities presenting as periparotid masses. A: Patient 1. Computed tomography (CT) study showing a well-circumscribed mass mainly anterior to the parotid gland with a thick slightly enhancing rim (arrow). No tract was found back to the external canal. B–D: Patient 2. MRI study of a child presenting with a periparotid mass with two previous attempted resections. In (B), the T2-weighted (T2W) image shows a fluid-appearing mass (arrows) surrounded by scar tissue (arrowhead) from previous surgery projecting into the tail of the right parotid gland, obviously involving the superficial portion of the gland. In (C), the T2W coronal image shows the multilobulated mass (arrows) becoming somewhat constricted superiorly, likely as a result of it forming a tract headed toward the external canal. In (D), the sagittal image shows the cystic mass (arrows) extending to a point of contact with the cartilage of the external auditory canal (arrowhead). D: Patient 3. A child presenting with a mass overlying the parotid region. CT study shows a mass in intimate contact with the junction of the bony and cartilage portion of the external auditory canal (arrow in E). F: Patient 4. A child presenting with a focal inflammation of the parotid gland. The mass is ill defined and fluid density with surrounding enhancement (arrow). This subsequently proved to be an infected brachial apparatus cyst.

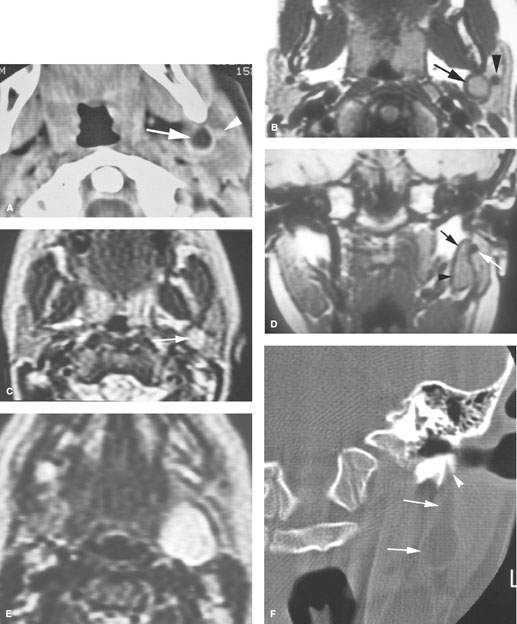

FIGURE 176.3. Two patients presenting with type II first brachial cleft cyst. The presentation was that of a mass at the angle of the mandible in the parotid region. A–F: Patient 1. In (A), a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) study shows the cystic tract (arrow) deep to the expected position of the facial nerve, which should be lateral to the retromandibular vein (arrowhead) on higher sections through the gland. In (B), a T1-weighted (T1W) image for comparison with (A) shows the same relationships (arrow). In (C), a T2-weighted (T2W) image shows the cystic nature of the mass (arrow). In (D), a T1W coronal image shows the fairly typical appearance of this type of brachial apparatus cyst, with the more dilated part of the cyst seen inferiorly (arrowhead). It tapers toward a potential tract toward the external auditory canal (black arrow) but clearly remains deep to the expected position of the main trunk of the facial nerve, which at this level in the parotid gland should lie just lateral to the retromandibular vein (white arrow). In (E), a T2W image shows the more expansile portion of the cyst that was noted clinically. In (F), the CT study was processed for bone windows to clearly show the extension of the tract into the lateral aspect of the bony external auditory canal (arrowhead), with the more expansile portion of the cyst seen deep to the parotid gland (arrows). G: Patient 2. Bone windows showing a cyst deep to the parotid gland (white arrow) with an expanded portion involving the external auditory canal (white arrowhead). This patient also had a middle ear congenital cholesteatoma (epidermoid cyst) (black arrow).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree