(1)

Princess Elizabeth Hospital Le Vauquiedor St. Martin’s Guernsey, Channel Islands, UK

(2)

Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, England UK

Abstract

Nonoperative diagnostic procedures such as needle core biopsy or fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) are essential for appropriate decision-making in the management of the patient with benign or malignant breast disease. A conclusive radiological and histological diagnosis of benign breast disease allays anxiety in the woman concerned, especially if this can be achieved without surgical operation. Inadequate sampling from fibrotic lesions, such as lobular carcinoma, hyalinised fibroadenomas and scattered microcalcification, now limits the use of FNAC, which was once a popular diagnostic modality. Consequently more and more units are using stereotactic needle core biopsies in combination or as an adjunct to FNAC as a diagnostic tool. Needle core biopsies benefit from a higher sensitivity and specificity than FNAC (Britton 1999). More sections can be cut, and immunocytochemistry stains carried out on a needle core biopsy which may assist in reaching a diagnosis in equivocal cases. Needle core biopsies are also preferred to localise excision biopsies as they potentially spare patients with benign lesions from unnecessary surgery.

Learning Points

FNAC is useful for diagnosis of fibroadenomas, apocrine cysts and lymph nodes.

Needle core biopsies may provide a definite diagnosis when compared to FNAC for fibrotic and calcified lesions.

The higher the number of needle core biopsies, the higher the diagnostic accuracy.

B3 lesions in needle core biopsies underestimate the presence of a high-grade lesion in a significant number of cases.

Specimen X-ray is important to confirm excision of screen-detected abnormality.

Ancillary immunocytochemistry such as CK5/6 may assist in confirming benignity.

5.1 Diagnostic Specimens in Benign Breast Lesions

Nonoperative diagnostic procedures such as needle core biopsy or fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) are essential for appropriate decision-making in the management of the patient with benign or malignant breast disease. A conclusive radiological and histological diagnosis of benign breast disease allays anxiety in the woman concerned, especially if this can be achieved without surgical operation. Inadequate sampling from fibrotic lesions, such as lobular carcinoma, hyalinised fibroadenomas and scattered microcalcification, now limits the use of FNAC, which was once a popular diagnostic modality. Consequently more and more units are using stereotactic needle core biopsies in combination or as an adjunct to FNAC as a diagnostic tool. Needle core biopsies benefit from a higher sensitivity and specificity than FNAC (Britton 1999). More sections can be cut, and immunocytochemistry stains carried out on a needle core biopsy which may assist in reaching a diagnosis in equivocal cases. Needle core biopsies are also preferred to localised excision biopsies as they potentially spare patients with benign lesions from unnecessary surgery.

Frozen section examination is not recommended in screen-detected lesions because of the risk of a false-positive diagnosis with lesions such as radial scars and sclerosing adenosis (Nielsen 1987). If one is faced with an equivocal FNAC or needle core biopsy diagnosis, it is preferable to perform an excisional biopsy and confirm the diagnosis on the paraffin-embedded tissue rather than risk a misdiagnosis on frozen section. Screen-detected lesions are usually small, and it is preferable to assess the whole lesion after appropriate fixation. Partly sampling the lesion for frozen section may distort the specimen, which could interfere with the final diagnosis. Even with a palpable lump, there is no justification for using frozen section for primary diagnosis.

5.2 Reporting Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology

Meaningful cytology results, especially in impalpable lesions, depend on the experience of the aspirator (usually the radiologist), the quality of the prepared slides (radiologist, pathologist or laboratory biomedical scientist), the quality of the staining (laboratory biomedical scientist) and the experience of the reporting pathologist or cytopathologist. The experience of the cytopathologist is enhanced by the volume of different cases reported in each unit, complimented by multidisciplinary team discussion of these cases. The UK National Health Service Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP 1993) devised a standardised format for reporting cytology similar to the radiological criteria. The criteria were updated in NHBSP Publication 50 (2001) which provides guidelines on nonoperative diagnostic procedures and reporting. The European Society of Mastology (EUSOMA) also applies similar reporting criteria (Perry et al. 2001).

5.2.1 Cytology Reporting Categories

C1 denotes an inadequate aspirate where there are no cells to represent the radiological or clinical lesion. With impalpable lesions, apparent inadequate sampling can occur with hypocellular fibrotic lesions, which would benefit from needle core biopsies. Scattered microcalcification can also produce an inadequate aspirate. The lack of epithelial cells in lipomas, cysts or fat necrosis should be reported in conjunction with radiological images to ensure that the appropriate lesion has been sampled. Again a needle core may assist with the diagnosis. Heavily bloodstained smears and poorly spread and stained smears, which preclude accurate cytological assessment, should be reported as inadequate. Repeat fine needle aspiration or core biopsy is recommended after the bleeding has settled, usually in 4–6 weeks.

C2 indicates a benign aspirate containing uniform cells arranged in monolayers. The background is usually ‘clean’ as opposed to the dirty background of a malignant aspirate. A mixture of myoepithelial and epithelial cells gives the ‘two-cell-type’ appearance because the myoepithelial cells take up more stain and appear darker than the ordinary epithelial cells. Fibroadenomas typically give this two-cell-type appearance. The presence of apocrine cells also indicates benignity (Fig. 5.1) in aspirates from fibrocystic change. Lipid-laden foamy macrophages from cysts or duct ectasia may also be present (Fig. 5.2).

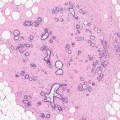

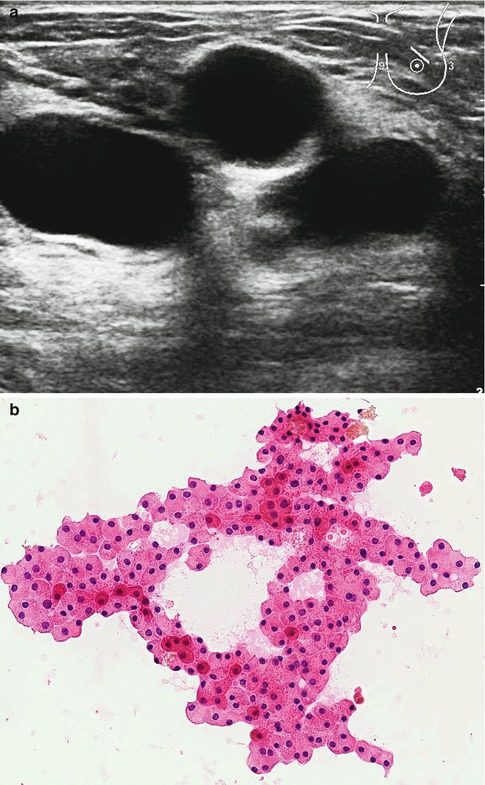

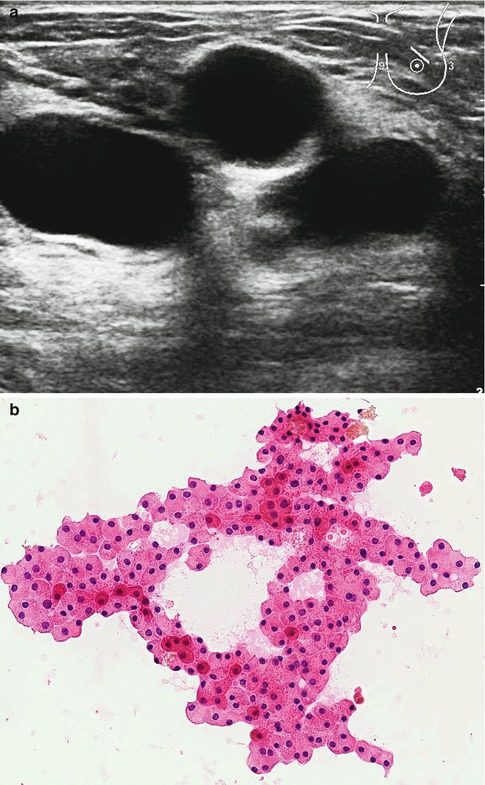

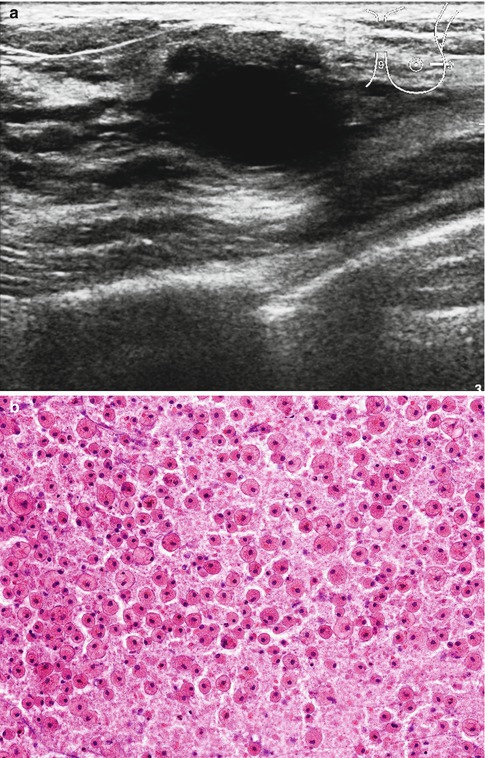

Fig. 5.1

(a) The ultrasound showed multiple cysts (U2). (b) The cytology showed layers benign apocrine cells; no malignant cell seen (C2). The haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) highlights the granular cytoplasm

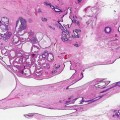

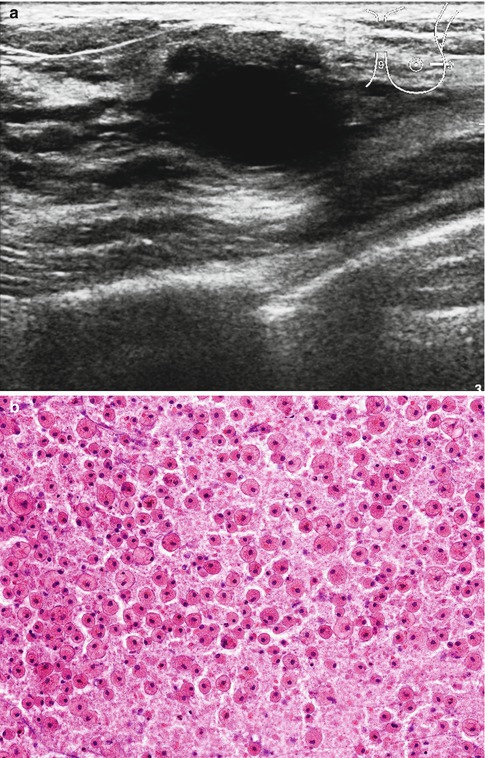

Fig. 5.2

(a) This ultrasound showed irregular cyst with contents (U3). The aspirate consisted of thick material resembling pus. (b) The cytology showed numerous macrophages in an amorphous background. No epithelial cells or malignant cell is seen (C2)

C3 cytology is reported in lesions where the aspirate shows a mixture of benign cells and atypical forms. The aspirate may contain monolayer cells with two cell types as well as pleomorphic cells with an increase in nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio; loss of cohesiveness may be present. These features occur in atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and some cellular fibroadenomas or may be secondary features of hormone replacement therapy. Depending on the mammographic appearance, lesions with C3 cytology should be followed up by short-interval mammography, needle core biopsy or excision biopsy.

C4 is designated to an aspirate containing atypical cells suspicious of malignancy, but there are other features preventing a definite diagnosis such as pauci-cellular material, poorly preserved cells or a mixture of benign and atypical cells, more pleomorphic than C3 cells. A core biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis before definitive surgical treatment.

C5 is reported in the presence of overtly malignant cells, which are pleomorphic and dissociated. Due to the widespread use of core biopsies, definitive surgical treatment is rarely made on C5 cytology. However, C5 cytology in an aspirate from metastatic carcinoma in a lymph node assists in appropriate management of the patient.

FNAC is the cheapest form of making a pathological diagnosis. The procedure is carried out in outpatient or radiology departments, and the patient can have the results on the same day. While FNAC is useful in the diagnosis of apocrine cysts, fibroadenomas and lymph nodes, due to the high risk of false-positive diagnosis, surgery for cancer should not be performed based on cytological diagnosis of C5 (Makunura et al. 1994).

5.3 Reporting Needle Core Biopsies

Needle core biopsies can be sampled under ultrasound or stereotactic guidance. Larger and high-volume needle core biopsies can be obtained by a vacuum-assisted device (mammotome). If the target abnormality is mammographic calcification, the needle core biopsies can be placed in a small cassette and X-rayed to confirm the presence of calcification. The cassette will then be submitted to the laboratory for processing.

At least three levels should be examined histologically to obtain an adequate diagnosis on needle core biopsies. The greater the number of needle core biopsies, the easier it is for the pathologist to make a diagnosis. Brenner et al. (1996) reported increased diagnostic accuracy with increasing number of needle core biopsies. With five biopsies, diagnostic accuracy was 98 % for masses, 91 % for calcifications, 100 % for masses with calcification, 100 % for focal asymmetries and 86 % for architectural distortions. Bagnall et al. (2000) reached a similar conclusion when they assessed 57 consecutive stereotactic needle core biopsies. The authors reported that the presence of calcification in the specimen X-ray was associated with a high sensitivity. The presence of five or more flecks in three or more needle core biopsies gave an absolute sensitivity of 100 % for carcinoma. The use of a vacuum-assisted device also reduces the rate of false-negative biopsies (Burbank 1997). If microcalcification is being sought, further levels should be examined before rendering an inadequate specimen. The pathologist should also be aware of calcium oxalate (weddellite) which can be present in the specimen X-ray but absent in the tissue unless examined under polarising light. Renshaw (2001) found out that at least five sections of the needle core biopsy are required in order to identify atypical small acinar proliferations or ADH.

The UK NHSBSP (2001) devised criteria for reporting needle core biopsies, which were later adopted by EUSOMA (Perry 2001). Although the needle core biopsy reporting categories are similar to those of radiological and cytological reports, the B3 category does not strictly follow the same criteria applied to radiology and cytology features (NHSBSP 2001).

5.4 Needle Core Biopsy Reporting Categories

B1 is applied to a needle core biopsy that contains normal breast tissue or adipose tissue. The presence of normal breast tissue in needle core biopsies should not be reported as benign in the presence of a radiological lesion, unless this has been discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting. Lipomas or hamartomas can give a B1 report; therefore, the clinical and radiological features should be taken into account when these lesions are suspected. Involuting lobules may contain microcalcification on histology, which was not apparent mammographically or on specimen X-rays. This microcalcification may not be representative of the radiological lesion, and a B1 report may be appropriate following multidisciplinary team discussion.

B2 confirms benignity in breast lesions such as fibroadenoma, fibrocystic change, sclerosing adenosis (Fig. 5.3) or fibrosis, with radiological evidence that the pathological lesion was sampled. Depending on the radiological features, the patient may return to routine screening.

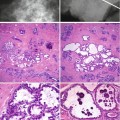

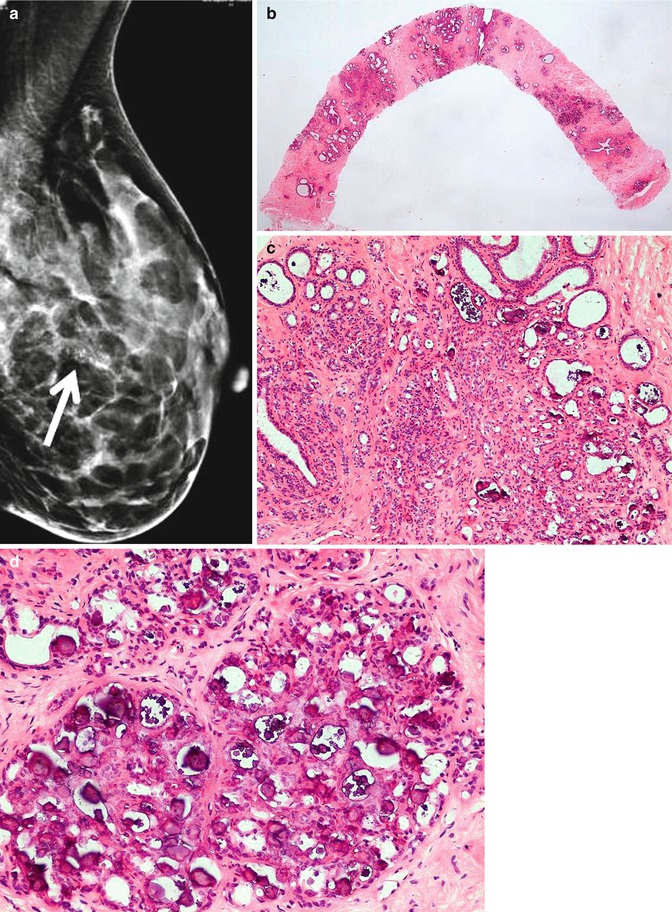

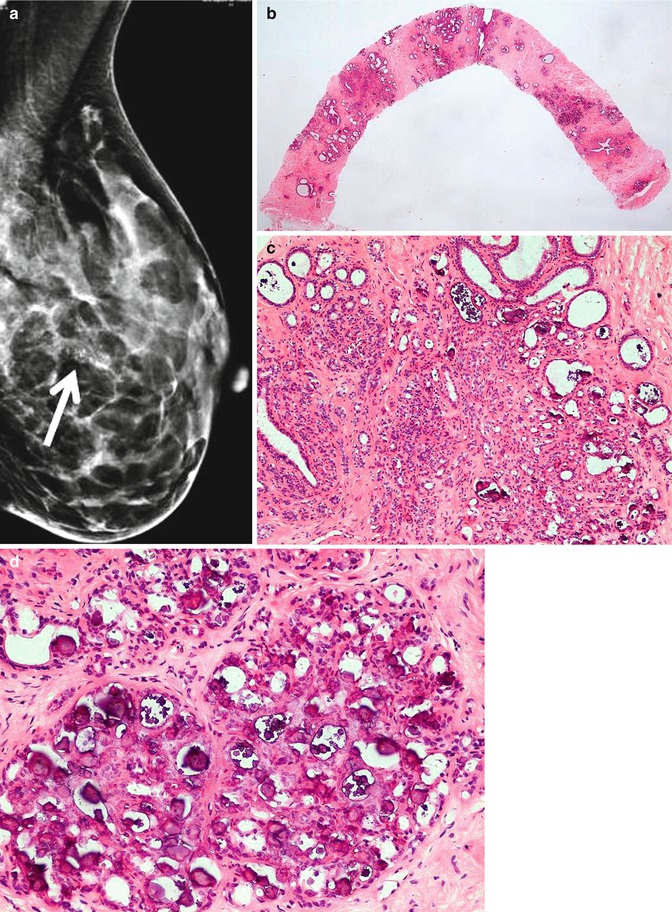

Fig. 5.3

(a) Symptomatic lump graded as benign, but mammogram revealed abnormal coarse calcification graded as R4. (btc) (b, c) The needle core biopsy showed sclerosing adenosis with coarse microcalcification (B2). (d) The lesion was excised because of radiological–pathological discordance. The excision specimen contained widespread calcifying sclerosing adenosis and other benign lesions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree