In pediatrics, one of the most common presenting symptoms to the pediatrician or emergency department is abdominal pain. It is a source of much consternation for parents and is often an extrapolated symptom by the parent based on how the child is behaving. Nearly one-fourth of patients younger than 15 years will have seen a physician for this problem. Abdominal pain may be defined as any discomfort that may be acute or chronic, constant or intermittent, or sudden or insidious. These variables, along with the patient’s age and accompanying symptoms or signs, play a role in the subsequent work-up of the problem and help determine the path that is most appropriate for diagnosis and treatment. The differential diagnosis is broad ( Table 5.1 ); therefore any signs, symptoms, or laboratory data that may narrow the differential are helpful. The history is crucial to arrive at a tailored diagnosis.

| 2 Months to 2 Years | 2–5 Years | >5 Years |

|---|---|---|

With Fever:

| With Fever:

| With Fever:

|

Scientifically, abdominal pain results from stimulation of nociceptive receptors and afferent sympathetic stretch receptors. Visceral pain is triggered by nociceptors of a hollow viscera as experienced in intestinal obstruction, appendiceal inflammation, and renal or biliary stones. Visceral pain is often referred and therefore not well localized. Parietal pain is associated with direct noxious stimuli to the parietal peritoneum, as demonstrated by tenderness at McBurney point or pain from irritation of the diaphragm. Alternatively, abdominal pain can be induced or psychosomatic in etiology, presenting as a manifestation of a psychosocial problem that may be rooted in the home or at school. These cases are the most difficult to sort out, and radiology is rarely helpful other than to exclude other demonstrable causes.

What Is the Role of Imaging in Abdominal Pain?

Imaging of the abdomen can help guide the clinician toward a surgical or nonsurgical approach and expedite the appropriate care of the child. The etiology for pain can be benign or gravely serious requiring immediate attention, which is part of the challenge to approaching these patients for the clinician. Unfortunately for the clinician, the spectrum of symptoms produced by these conditions can often be vague and nonspecific, and for this reason imaging plays a prominent role in the evaluation of these patients. A complete history and physical examination are necessary to direct the imaging workup. Often a screening radiograph of the abdomen is most useful to assess the need for further imaging or to determine the need for immediate surgical intervention ( Table 5.2 ). The decision to image or not often depends on the acuity of the presenting symptom; therefore to direct the imaging most logically, an algorithm may help direct the workup where the initial distinction is acute versus chronic. After this, the age of the patient, along with the presence or absence of fever, might mark the next branch point in the decision tree. Associated symptoms and signs will lead down directed pathways to finally arrive at a concise differential diagnosis. When the starting symptom is as broad as abdominal pain, even a directed algorithm will still result in a differential diagnosis rather than a single final answer.

|

How to Approach the Abdominal Radiograph in Pediatrics

There are many approaches to interpreting abdominal plain film, some of which are guided by catchy mnemonics. All of these have in common the goal of being systematic so as not to neglect any one aspect of the film. This can happen when there is a positive finding, the so-called satisfaction of search. Although ordering a plain radiograph is frequently a knee-jerk reflex for the clinician, it is important to understand the limitations of the examination. Not surprisingly, the plain abdominal radiograph is often as nonspecific as the presenting complaint. There is broad variability in the interpretation and agreement among radiologists. Thus the final interpretation of a “nonspecific bowel gas pattern” is often considered a nondiagnostic examination (see Box 5.1 ).

Inside-out, outside-in

Gas, mass, bones, stones

CBA (chest, bones, abdomen)

A-A-I-I-M-M:

- ▪

Adhesions

- ▪

Appendicitis

- ▪

Intussusception

- ▪

Inguinal hernia

- ▪

Malrotation

- ▪

Miscellaneous (Meckel, tumor, duplication, etc.)

How to Describe the Overall Gas Pattern

Many terms are used in the radiology lexicon to describe both specific and nonspecific gas patterns. Radiologists should be familiar with the various descriptions, their implied meanings, and the interpreted meaning by the referring doctor.

Normal Gas Pattern

When evaluating the bowel by radiograph, we are looking at the gas pattern, because the air interface with the adjacent tissue is really what is being imaged. Normal position of the bowel is the first assessment. The stomach typically contains air and is located in the left upper quadrant. The small bowel is often central and should be relatively uniform where it is air filled ( Fig. 5.1 ). One should be careful in using adult criteria for bowel obstruction, such as dilation of bowel loops longer than 3 cm, because this may lead to underdiagnosis in children. Average bowel diameter in infants is approximately 1.2 cm at 6 months of age, increasing to 2.1 cm by 8 years of age, and reaching average adult diameter by 15 years. One should be able to see the valvulae conniventes traversing the small bowel loop in older patients, but in the young toddler and infant, these may not yet be visible. Large bowel is typically located on the periphery, and the haustral markings can be seen more widely spaced apart and partially indenting the gas-filled looped on either side ( Fig. 5.2 ). In younger children, haustra may not be present. Depending on the timing of imaging, a variable amount of formed stool may be seen in the colon. The delayed development of haustral markings and visibility of small bowel plicae can make bowel evaluation and localization of the problem in the youngest patients more difficult.

Ileus

Ileus is typically adynamic. Adynamic ileus refers to a functional or nonanatomic etiology for the obstruction of gas in the small bowel, or a functional paralysis of the bowel. Because there is no anatomic obstruction, there is no disproportionate dilation of upstream bowel. Therefore the bowel loops are either uniformly dilated or uniformly without any gas ( Fig. 5.3 ). These patients may present asymptomatically or with signs and symptoms of an anatomic obstruction. Typical clinical settings include sepsis, trauma, and metabolic disturbances (see Box 5.2 ).

Clinical findings: Abdominal distention with or without obstructive symptoms (i.e., vomiting)

Imaging findings:

- ▪

Uniform air-filled distention of nondilated bowel

- ▪

Localized: sentinel dilated loop

- ▪

Presence of distal colonic gas

Obstruction

A mechanical blockage, either intrinsic or extrinsic, to the passage of air or fecal content in the bowel results in obstruction. The radiographic appearance is specific with dilated bowel loops proximal to the point of obstruction and decompressed bowel distal to that point. Conversely, in later obstruction the bowel may be fluid filled and dilation difficult to assess, thus the importance of an orthogonal view. There are often cases where variation in timing of the obstruction leads to anomalies in the gas pattern. Some experts describe the appearance of obstructed bowel loops as “sad sausages” ( Fig. 5.4 ) in reference to their smooth, featureless appearance, in contrast with “happy polygons” (see Fig. 5.1 ), which describes the normal wall variability seen in nonobstructed bowel. The “string of pearls” or “string of beads” sign refers to the appearance of trapped air between the valvulae conniventes in a predominantly fluid-filled small bowel loop. These gas bubbles may appear stacked or side by side in a string. Alternatively, there may be a “stepladder” configuration of small air–fluid levels in the obstructed small bowel ( Fig. 5.5 ; see also Box 5.3 ).

Clinical findings: Abdominal distention, pain, and vomiting

Imaging findings:

- ▪

Dilated bowel loops upstream of the transition

- ▪

Decompressed distal loops

- ▪

Air–fluid levels

- ▪

“String of pearls” sign in late obstruction

- ▪

“Sad sausages”

Age-Based Differential Considerations

The broad range of etiologies that may cause acute-onset abdominal pain in children overlaps across age groups, although some may be more typical than others in each age group. We will discuss each of these entities in detail, but keep in mind, many of these diagnoses may be seen in all age groups. In most cases, when a child presents with acute abdominal pain, the most pressing question is whether the child needs an operation, or can surgery be prevented in the near future by intervening/acting on an important finding.

Infants Beyond the Neonatal Period

The etiology of abdominal pain in infants between 2 months and 2 years of age may be difficult to diagnose because symptoms are largely interpreted based on physical signs. Mechanical causes for pain are the most important to exclude, most commonly, intussusception and volvulus. Less common causes of acute abdominal pain in this age group include appendicitis, sepsis, and obstruction as a result of adhesions. Although the most common causes for abdominal pain may be non-life-threatening, such as colic or enteritis, the clinician needs to maintain a high level of suspicion for less common but possibly life-threatening causes for pain in this age group, such as nonaccidental trauma.

Toddlers and School-Age Children

Abdominal pain in toddlers and young school-age children is a common problem. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics, the incidence of children aged 0 to 4 years presenting to either the outpatient setting or the emergency department with abdominal pain was approximately 268 per 10,000 as of 2010. The causes of abdominal pain in this age group can range from the annoying but relatively benign (constipation, gastroenteritis) to life-threatening (appendicitis, intussusception). Unfortunately for the clinician, the spectrum of symptoms produced by these conditions can often be vague and nonspecific, and for this reason imaging plays an important role in the evaluation of these patients.

Right lower quadrant pain in toddlers and young children is a frequent presenting complaint, the etiologies of which range from the emergent, such as appendicitis and intussusception, to the self-limited, such as mesenteric adenitis. Evaluation often begins with radiographs, due to widespread availability, rapidity of the exam, and lack of need for patient prep or sedation. Findings on radiographs are frequently nonspecific, however, which may prompt a need for more advanced imaging, such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The availability of these more advanced imaging modalities varies with the facility to which the patient presents, and transfer to higher-level facilities may be needed to accomplish this imaging.

Bowel obstruction on plain radiographs can be one of the quickest methods to distinguish serious from benign conditions. Causes of bowel obstruction in young children are generally going to be those potentially requiring surgical intervention, such as appendicitis, intussusception, or Meckel diverticulum. The AAIIMM mnemonic (appendicitis, adhesions, intussusception, inguinal hernia, Meckel, malrotation) can be a helpful reminder of some of the conditions producing bowel obstructions in children.

Patient age and clinical symptoms are important to narrow the differential diagnosis when a bowel obstruction is recognized. Intussusception typically occurs in patients 3 months to 3 years of age and is typically accompanied by crampy abdominal pain, fussiness, lethargy, and, possibly, bloody stools (“currant jelly stool”). Appendicitis is seen more frequently in older pediatric patients (10–19 years old) and is associated with fever, leukocytosis, nausea/vomiting, and anorexia. In toddlers and younger children who may not be able to verbalize their symptoms, the diagnosis of appendicitis is more likely to be delayed and present with appendiceal perforation. In these patients, symptoms may include vague abdominal pain and distention, fussiness, or lethargy, in addition to fever and vomiting.

Older Children and Teenagers

The range of pathology that may present with abdominal pain in the older child age group is broad, but often can be limited by the history that is more easily obtained in these patients. Although many of the diagnoses that are imaged require cross-sectional imaging to diagnose, the abdominal plain film is again frequently a good starting point.

Important factors to consider from the history are the duration of pain, the acuity of onset of pain (versus an insidious onset), the quality of the pain, and associated symptoms, such as vomiting, diarrhea, or fever. Finally, exposures are an important piece of information that may provide an etiology for a suspected infectious cause.

Acute abdominal pain may be emergent or life-threatening, but in the majority of patients, this is not the case. The clinician is tasked with determining the urgency of pain, and the radiologist is often consulted. We will discuss the more common causes of abdominal pain in children later in this chapter, focusing on those etiologies where radiology may play an important or diagnostic role in the workup.

Common Diagnostic Etiologies for Abdominal Pain Across Age Groups

Malrotation With Midgut Volvulus

Malrotation/midgut volvulus is a true life-threatening surgical emergency and should be suspected in any infant with acute-onset bilious vomiting. Although it is usually diagnosed in the neonatal period, a delayed presentation of malrotation with midgut volvulus must still be at the top of the differential diagnosis for bilious emesis in any age group. Because of its short mesentery, malrotated bowel is at risk for volvulus with secondary bowel ischemia, which can result in complete loss of the midgut and even death.

Plain radiographs are often normal, because volvulus presents early after the twisting of the bowel and there is little time for dilation of the upstream bowel. The diagnostic imaging study of choice is the upper gastrointestinal (GI) series. In a normal study the position of the duodenojejunal junction has a rigid fixed location to the left of midline, just left of the left pedicle at the same level as the duodenal bulb. This marks the fixation by the ligament of Treitz, which traverses the mesentery diagonally, also fixing the cecum in the right lower quadrant. In a well-performed upper GI series, almost any deviation from the normal examination is highly suspicious for malrotation ( Fig. 5.6 ).

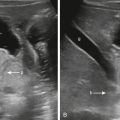

When patients with malrotation/midgut volvulus present with vomiting that is not recognized as bilious, the diagnosis of pyloric stenosis may be suspected, resulting in an ultrasound of the abdomen. Sonographic findings that suggest malrotation include reversal of the position of the superior mesenteric artery and vein positions ( Fig. 5.7 ; see Box 5.4 ; also refer to Chapter 4 , Vomiting Infant).

Clinical findings: Acute-onset bilious vomiting in an infant, crampy abdominal pain

Imaging findings:

- ▪

Radiograph: Typically normal bowel gas pattern; Can be dilated in late diagnosis

- ▪

UGI: malposition of the duodenojejunal junction

Downward spiral of the duodenum/jejunum

Abrupt cessation of contrast passage in the third portion of the duodenum

- ▪

US: reversal of the SMA/SMV, whirlpool sign

Colonic Volvulus

Children with colonic volvulus typically present with continuous, severe abdominal pain and colonic dilatation. The pain in the colonic volvulus may be described as colicky, mimicking episodes of peristalsis. Vomiting may occur several days after the onset of pain. Children who have a history of colonic dysmotility or chronic constipation may as a result have a redundant sigmoid colon that can increase the possibility of volvulus ( Fig. 5.8 ). Similarly, patients with a narrow mesenteric attachment, either congenitally or secondary to prior bowel surgery, may also be at risk for development of colonic volvulus. Cecal volvulus is uncommon in children and may be seen in patients with intestinal malrotation or abnormal fixation with adhesive bands (see Box 5.5 ).

Clinical findings: Insidious-onset pain and distention, vomiting, constipation

Imaging findings:

- ▪

Colonic dilation

- ▪

Cecal “bascule”

- ▪

Bird beak in ascending colon

Imaging in sigmoid volvulus:

- ▪

Colonic dilation

- ▪

“Coffee bean” sign

- ▪

Absent rectal gas

- ▪

Beaking distally on contrast enema

Intussusception

Intussusception is a telescoping of a proximal segment of bowel (the intussusceptum) into a more distal segment (the intussuscipiens). Intussusception may involve the small intestine only (enteroenteric), small intestine and colon (ileocolic), or colon only (colocolonic). The variety that is of particular concern for the radiologist is the ileocolic intussusception because this can be reduced by a therapeutic enema performed under fluoroscopic guidance.

Ileocolic intussusception is a commonly suspected diagnosis in the infant and toddler age group. Nearly 60% of children with ileocolic intussusception are younger than 1 year, and 80% to 90% are younger than 2 years. In children 6 months to 3 years of age, ileocolic intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction. Prevalence varies by locale, and an overall prevalence is not established; however, the estimated incidence in the United States is approximately 1 in 2000 live births. There is a seasonal variation, with peaks coinciding with peaks in viral gastroenteritis in some geographic regions. This correlates with the hypothesized etiology for idiopathic ileocolic intussusception in that a preceding viral infection causes lymphoid hyperplasia or enlargement of Peyer patches (submucosal aggregated lymphoid tissue in the ileum) that serves as a lead point. In patients outside the typical age range (younger than 3 months, older than 6 years), a pathological lead point is more likely, such as a Meckel diverticulum, duplication cyst, polyp, or lymphoma.

Patients with intussusception may have a variety of symptoms, including colicky abdominal pain alternating with periods of quiescence, lethargy, bloody or “currant jelly” stools, and vomiting that may be bilious. Symptoms may be vague and insidious initially, mimicking more benign processes, such as gastroenteritis, and leading to delay in presentation.

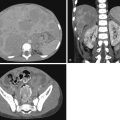

As in many cases of abdominal pain in children, the initial evaluation of potential ileocolic intussusception is often with abdominal radiographs. Possible abnormalities detected on radiographs include a right lower quadrant soft tissue mass with or without meniscus sign, bowel obstruction, or paucity of gas within the right lower quadrant ( Fig. 5.9 ). Radiographs have been shown to be unreliable for diagnosis of ileocolic intussusception in numerous studies, with a sensitivity of 60% and specificity of 26% for a supine abdominal radiograph, and only 74% and 58%, respectively, for a two-view x-ray series. In fact, in up to 25% of cases, the abdominal radiographs may be completely normal. Conversely, the negative predictive value of the three-view abdominal radiograph was shown to be quite high. That is, when the presence of an air-filled cecum and an otherwise normal bowel gas pattern can be definitively seen, this may be sufficient to exclude the presence of intussusception. Radiographs are also helpful in excluding bowel perforation, a contraindication to therapeutic enema for intussusception reduction. Although radiographs are frequently obtained, the definitive presence of intussusception is rarely indisputable, and a follow-up confirmatory test is usually required.

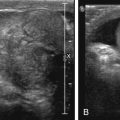

The imaging modality of choice for diagnosis of intussusception is abdominal ultrasound. Ultrasound is readily available in most institutions, is portable, requires no patient prep or sedation, and uses no ionizing radiation. When an ileocolic intussusception is present, there is usually no diagnostic dilemma, because a large soft tissue mass is immediately evident. The classic ultrasound findings are of the “target” or “bull’s-eye” sign when the intussusception is imaged in the short axis and the “pseudokidney” sign when imaged longitudinally ( Fig. 5.10A–C ). The alternating layers seen in the target sign represent the outer intussuscipiens, a middle layer of mesenteric fat and lymph nodes, and the inner intussusceptum. Ancillary findings that may be helpful to note include the presence of free fluid, decreased blood flow within the involved bowel segments on Doppler interrogation, and “trapped” fluid between the layers of the intussusception (see Fig. 5.10D ). These findings can indicate that therapeutic enema may be difficult or unsuccessful, but they do not contraindicate the procedure.

Treatment of ileocolic intussusception is with therapeutic enema or surgery. Enema is generally attempted first because of its less invasive nature, with failures of reduction proceeding surgery. Contraindications to therapeutic enema include presence of bowel perforation/free air, peritonitis, or a patient in shock. Details of the performance of therapeutic enema are beyond the scope of this text (see Box 5.6 ).

Clinical findings: Colicky abdominal pain alternating with periods of quiescence, lethargy, bloody stools, +/− bilious vomiting

Imaging findings:

- ▪

Paucity of gas in the RLQ

- ▪

Meniscus sign on the left lateral decubitus view

- ▪

Mass visualized with meniscus sign

- ▪

Bowel obstruction in an otherwise healthy 6-month-old to 3-year-old child

- ▪

“Target” or “pseudokidney” sign on ultrasound

Appendicitis

Appendicitis remains the most common cause of acute abdominal pain presenting to the emergency department among adults and children. In the United States, about 70,000 pediatric cases per year are diagnosed, with the majority of affected children in the second decade of life (10–19 years old). Appendicitis is considered a surgical emergency and can be life-threatening. If undiagnosed, it can progress to rupture and peritonitis with development of intraabdominal abscesses. Therefore early diagnosis is key to preventing morbidity from this disease. Clinically the most predictive indicator in an older child is pain that localizes from the periumbilical region to the right lower quadrant, which occurs as the process changes from visceral to parietal stimulus of pain receptors. Subsequently, patients may show abdominal wall rigidity on physical examination (see Box 5.7 ).

Clinical findings: Abdominal pain often periumbilical and becoming localized to the RLQ, low-grade or no fever, early-on anorexia

Imaging findings:

- ▪

Radiographs: Normal or vague ileus, +/− Paucity of gas in the RLQ, +/− Appendicolith

- ▪

US: enlarged appendix >6 mm, hyperemia, echogenic periappendiceal fat, fluid collection

- ▪

CT/MRI: enlarged, enhancing appendix >6 mm, fat stranding, fluid collection, +/− appendicolith

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree