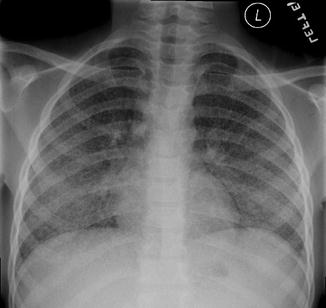

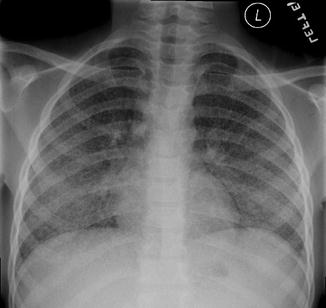

Fig. 19.1

Tuberculosis in a young boy. (a, b) Frontal and lateral radiographs of the chest demonstrate a right upper lobe opacity and associated right hilar lymphadenopathy

Miliary disease, a complication of primary infection, is defined as manifestation of disease that leads to discrete tiny nodules diffusely throughout two or more organs (Fig. 19.2). This form of TB is more common in very young patients and immunosuppressed [8, 14]. When there is reactivation of primary TB, upper lobe predominant fibrosis and architectural distortion with cavitation are characteristic radiographic signs.

Fig. 19.2

Miliary tuberculosis in a 9-year-old male. Diffuse discrete tiny nodules are seen throughout the bilateral lung consistent with complication of primary infection. Miliary TB is a common manifestation in young and immunosuppressed patients

Children are particularly prone to extrapulmonary tuberculosis, which most often occurs in the abdomen, central nervous system, bones, joints, and skin [16]. Ussery [17] found that 22 % of patients younger than 15 had only extrapulmonary disease. Morbidity and mortality associated with TB is greatest when there is CNS involvement, especially with tuberculous meningitis, which can lead to blindness, deafness, intracranial calcifications, diabetes insipidus, and mental retardation. Of the patients presenting with meningitis, 80 % of these patients are younger than age 4 [17].

The abdomen is the most common site of extrapulmonary TB. Abdominal involvement can be seen with or without associated lung disease. Abdominal radiographs may demonstrate calcifications in the liver, kidneys, adrenals, or bladder. If available, CT can demonstrate additional findings, including lymphadenopathy and changes affecting the ileocecal region of the bowel. When there is intestinal involvement, the ileocecal region is affected 90 % of the time with the cecum and terminal ileum being contracted with wall thickening [16]. Enlarged lymph nodes may be seen in the mesentery and omentum, characteristically with hypoattenuating centers and hyperattenuating, enhancing rims. Renal involvement may be manifest on CT, and occasionally on radiographs, as renal calcifications. Caliectasis and hydronephrosis may also be seen [16]. TB can also involve the adrenal glands. When bilateral, this can lead to adrenal insufficiency. Classic imaging findings include small adrenal glands with calcifications [18].

Musculoskeletal involvement is most often seen in the spine (50 %). Tuberculous spondylitis most commonly affects the lower thoracic and upper lumbar spine [19]. The infection is due to hematogenous seeding of the vertebral bodies originating in the end plates. In children, the hematogenous spread may seed the disc instead which can lead to vertebral destruction and associated paravertebral soft tissue masses. Another musculoskeletal complication is septic arthritis leading to erosions and destruction of the joint (Fig. 19.3) [16].

Fig. 19.3

Tuberculous arthritis. Most commonly affects the hips and the knees. Reactive hyperemia leads to juxta-articular osteoporosis, erosions and, in this 9-year-old boy, severe joint space narrowing

HIV/AIDS

HIV/AIDS has devastated children of the developing world in many ways. Thirteen million African children have been orphaned due to their parents having died from AIDS. Many more are infected directly, most often acquiring the virus through vertical (mother-to-child) transmission.

One third of infants born to HIV-infected mothers acquire the virus through a combination of intrauterine, intrapartum, and postpartum exposures [20]. Many more acquire the virus through breastfeeding, which in most instances is the only form of nutrition that these children will receive. The 30–35 % rate of vertical transmission in the developing world compares to a rate of only 4–6 % in the developed world, where highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and formula feeding are readily available [21]. There are approximately 1,500 new pediatric cases of HIV per day in sub-Saharan Africa [22].

Once infected, children with HIV in the developing world are particularly prone to complicating infections due to poor nutrition, lack of access to clean water and health care, as well high prevalence of gastrointestinal and respiratory pathogens in the community [22]. Opportunistic infections seen in HIV-infected children most often involve the upper and lower respiratory tract infections, the intestine, and the brain.

Although HIV/AIDS predisposes its host to unusual and opportunistic infections, the most common infections are community-acquired. In one study by Chakraborty, 58 % of HIV-infected children died from pyogenic pneumonia [22]. The most common respiratory infection is of bacterial etiology. Fifty percent are focal and consolidative, while 50 % are diffuse, nodular or form cavities. Findings of bronchopneumonia in HIV patients have significant overlap with those of TB.

AIDS patients are predisposed to opportunistic infections such as PCP (Pneumocystis pneumonia), although its prevalence may be decreased where HAART and prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) are available [11]. Chest X-ray (CXR) findings can be normal in up to 40 % of patients with PCP. Others will have bilateral perihilar finely granular, reticular, or ground glass opacities (Fig. 19.4) [23]. Other opportunistic fungal infections may demonstrate focal alveolar opacities or multiple pulmonary nodules.

Fig. 19.4

PCP in an HIV-positive young adult. Diffuse granular and reticular opacities in a perihilar distribution. The incidence of PCP has significantly decreased with TMP-SMX prophylaxis

HIV-infected pediatric patients may also suffer from dilated cardiomyopathy that may be due to immune-mediated mechanisms, opportunistic infections directly invading myocardial cells, or primary infection of myocardial cells by HIV itself [21]. The CXR may reveal cardiomegaly, and in severe cases, congestive heart failure. HIV-associated nephropathy may lead to proteinuria, hematuria, renal tubular acidosis, and end-stage renal disease. Sonographic findings include large, echogenic kidneys and decreased corticomedullary differentiation (Fig. 19.5) [24].

Fig. 19.5

An HIV-positive male with diffusely echogenic right kidney consistent with HIV nephropathy. There is loss of corticomedullary junction, and there is a clear increase in echogenicity of the kidney in relation to the normal liver

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is a significant public health risk in the developing world. Although often thought of as simply a nuisance in the developed world, diarrhea leading to dehydration is one of the leading causes of death of children in the developing world; lack of clean water is the major cause, although other endemic disease such as HIV are also significant contributors. Common pathogens causing diarrhea in children include rotavirus and Escherichia coli [26], and in the HIV population, other pathogens must be considered, including cytomegalovirus, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI), Giardia, and cryptosporidiosis [26, 27].

Imaging does not play a major role in the diagnosis and management of the child with diarrhea; in particular, radiographs of the abdomen are rarely helpful as many of the imaging findings are not specific to any particular disease entity. For example, there may be focal dilatation of small bowel loops, air fluid levels, or bowel wall thickening, primarily due to malabsorptive fluid loss [28].

If needed, the small bowel can be more thoroughly evaluated with an upper GI study with small bowel follow through, which is a study that requires fluoroscopy and barium (or another suitable oral contrast agent). In performing this study, transit time of contrast is worth noting, as normally barium passage through the small bowel usually occurs in 1–2 h. Note that in the diarrhea workup, in contrast, transit time can be normal, short, or longer than normal. This study may also reveal bowel wall thickening, particularly in the setting of CMV (thickened and edematous folds with deep ulcers and ulcerations), MAI (diffuse enteritis with thickened folds and a micronodular mucosal patterns), candidiasis (diffuse mucosal edema and linear filling defects), and cryptosporidiosis (secretory enteritis with thickened folds). Another common etiology for diarrhea is Whipple disease, caused by Tropheryma whipplei which preferentially affects the duodenum and proximal jejunum with thickened mucosal folds [29].

Malaria

Imaging plays little role in the diagnosis of malaria, as the diagnosis is based on peripheral blood smears and clinical history. Imaging, however, may show findings concordant with the diagnosis of malaria. For example, ultrasound of the abdomen may reveal hepatosplenomegaly [31]. In fact, in presentation of children with acute abdominal pain, it is important to note that a life-threatening complication of malaria is splenic rupture, due to acute splenic enlargement and infarction, and emergent ultrasound in the setting of acute abdominal pain and malaria infection can help identify this complication [33].

Parasitic Infections

Echinococcus, the pathogen leading to hydatid disease, is still a frequent cause of liver and lung disease in many countries in the developing world. Hydatid disease is endemic in China, Africa, the Mediterranean, Balkan Countries, the Middle East, and South America, but is now being seen more commonly in the developed world due to globalization and migration [34].

The most common routes of infection are through ingestion of contaminated water or uncooked food, or from direct hand-to-mouth fecal transmission, as can often occur in settings of low socioeconomic status and poor sanitary conditions [35]. Close human contact with dogs and livestock pose a particular risk. Serological tests can be used to confirm the presence of hydatid disease if available, but rely on a competent immune response, which can be lacking if the patient has an underlying disease like HIV. Furthermore, the sensitivity of tests is inversely proportional to the degree of sequestration of the echinococcal antigens inside of cysts, causing the diagnosis to be elusive [36].

The liver is involved in 50–89 % of cases of hydatid disease, more than the lung (10–30 %) and other organs (10–20 %) [37]. Most often, liver involvement takes the form of a solitary cyst although multiple liver cysts may also be seen [38]. Classic radiographic findings include hepatomegaly and scattered radiolucencies which are outlined with calcified rings which is seen in up to 30 % of cases on plain radiographs [39]. Densely calcified cysts are usually thought to represent inactive disease [40]. There is a predilection for involvement of the right lobe of the liver. Portable ultrasonography machines can be highly sensitive for cystic hepatic disease when available; ultrasound findings in unilocular hydatid disease include a smooth-walled cyst with an anechoic fluid content with posterior acoustic enhancement. A cyst can also have mobile, dependent, echogenic hydatid, which is composed of brood capsules and free scolices [41]. Multivesicular cysts may demonstrate a honeycombing pattern with multiple septa representing the walls of the daughter cells. If CT is available, classic findings of Echinococcus show a mass with central necrosis and septations with a plaque-like rim of calcifications (Fig. 19.6) [34].

Fig. 19.6

Echinococcus (hydatid) disease. An 18-year-old male from Egypt with right upper quadrant pain. There is a large complex cystic mass within the right lobe of the liver. Numerous septations are also seen. Furthermore, the wall of the hydatid cyst is well defined without definitive surrounding edema

The radiologist should be aware of several important complications of hydatid cyst disease. For example, rupture of a hydatid cyst can occur in as many as 90 % of cases and can often be clinically silent, but may lead to anaphylaxis due to release of antigens [34, 39]. Both US and CT can demonstrate a cyst wall defect with passage of cyst contents outside of this defect, and clinicians should be immediately notified and clinical anaphylaxis precautions arranged.

In addition to rupturing, hydatid cysts may become secondarily infected with bacteria, in which case the patient may present with right upper quadrant pain, leukocytosis, and fever. US findings of a secondarily infected cyst are nonspecific and demonstrate poorly defined margins with a solid appearance, mixed solid and fluid appearance with internal echoes, and air fluid levels. CT is more sensitive, and findings include a poorly defined mass and a high attenuation rim suggesting an abscess surrounding the underlying cyst; gas and air fluid levels can also be seen [34].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree