In 2000, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its report

To Err Is Human, drawing attention to widespread errors in the practice of medicine.

1 Subsequent increased regulatory and public scrutiny of physician performance lead to the practice of peer review as a method to monitor physician performance. Peer review became more integrated into the practice of medicine through requirements published by The Joint Commission (TJC), the primary accreditation body for hospitals. TJC published new guidelines in 2004 mandating collection and use of provider-specific performance data in the credentialing and recredentialing processes, including clinical judgment, technical skills, communication, professionalism, and continued education and improvement.

2 In 2007, TJC revised these guidelines to emphasize the alignment of provider-specific data with the six core competencies developed jointly by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of Medical Subspecialties (ABMS).

3 These core competencies include patient care, medical and clinical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and system-based practice.

As with other medical specialties, radiology as a profession needed to develop a peer-review model that satisfied both public and regulatory pressures driving monitoring of physician performance. The American College of Radiology’s (ACR) RADPEER program, which was developed as direct response to the IOM’s

To Err Is Human report and made available in 2005, became the stimulus for radiologists to become regularly engaged in peer review.

4 RADPEER enables participating radiologists and practices to compile individual and practice peer-review data stratified by modality and practice site and compare with other national performance data. Currently, the ACR reports that more than 17,000 radiologists actively participate in the program.

5 However, RADPEER, while popular among practicing radiologists, is only one part of the bigger peer-review process. Other methods of peer review include double reads, consensus-oriented group review, focus practice review, practice audit, and correlation with operative and pathologic findings (

Table 11.1).

The central goal of peer review in radiology is to improve patient outcomes by reducing interpretative and procedural errors. Deciding how to institute a peer-review program can be challenging because each model of peer review has its own advantages and disadvantages. Radiologists may object to this new “intrusion” into their practices because of real or perceived bias among reviewers, unclear policies, lack or perceived lack of transparency, absence of evidence-based reference standards for many cases, additional time pressures on an already busy practice, belief that peer review will not lead to improved patient care, and even legal concerns.

MEASURING PERFORMANCE IN RADIOLOGY

To effectively measure radiologists’ performance, metrics must be relevant to individual radiologists, practice leadership, credentialing bodies, and society as a whole. Metrics should be readily reproducible and chosen on the basis of published evidence or established standards or guidelines and should be applicable to each radiologist’s respective practice.

3 Furthermore, a sufficient number of data points should be obtained to ensure that data are meaningful (

Figs. 11.1,

11.2,

11.3). For example, some authors recommend that 3% to 5% of interpreted examinations undergo peer review,

6 arguing that reviewing only 0.1% of a radiologist’s reports may not fully demonstrate a radiologist’s true performance level. However, this recommendation is arbitrary and is not supported by any published scientific evidence.

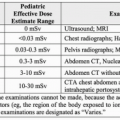

7Diagnostic accuracy is the most appropriate and ostensibly the most important performance metric in diagnostic radiology because of its direct relationship to patient outcome.

8 However, medical imaging is typically only one part of the diagnostic workup, and patient outcome is usually the result of many factors, including natural history of disease and patient’s response to therapy. Additionally, errors made on diagnostic imaging studies can have variable impact on patient management or ultimate outcome. For example, failing to detect a 2-cm colon carcinoma on an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan will likely significantly adversely affect patient outcome whereas inaccurately characterizing the pattern of advanced fibrosing diffuse lung disease on a chest CT scan may have little impact on patient outcome.

Adherence to agreed-upon practice guidelines is another performance indicator that can be measured for each radiologist. For example, a radiology practice can agree to use the Fleischner Society’s published guidelines for management of incidentally detected small lung nodules,

9 and adherence to and appropriate use of these guideline can be measured for each radiologist as a component of peer review. Variability in recommendations for managing imaging findings can be confusing to referring physicians and patients.

Radiologist performance can also be evaluated by soliciting feedback from colleagues, trainees, staff, and patients. Specific attributes such as communication skills, professionalism, and “good citizenship” within a department can be assessed. A summary of personal evaluation and review of patient or staff complaints or commendations can be included as a component of a professional practice evaluation in addition to clinical skills.

For a peer-review process to be effective, it should be fair, transparent, consistent, and objective. Conclusions should be defensible, and various opinions should be included. Peer-review activities should be timely, result in useful action, and provide feedback through auditing

6,10.