Pelvic pain in a preadolescent or adolescent girl can be a diagnostic challenge. Ovarian causes, including torsion of the ovary, ovarian cysts, and paraovarian cysts, must be distinguished from nonovarian diagnoses, such as appendicitis, renal calculi, urinary tract infection, and even intussusception in younger children. Because ovarian or fallopian tube torsion are emergent situations, rapid diagnosis is key.

What Imaging Modality Is Best to Assess Pelvic Pain?

Ultrasound is the most useful imaging modality for evaluating the ovaries. A transabdominal approach is typically performed in adolescence. A full bladder is necessary for optimized transabdominal pelvic ultrasound. In the optimized setting the ovaries are well visualized, and the study is quick. If the patient is unable to drink, bolus intravenous fluids can be given, or if emergent diagnosis is necessary, a Foley catheter can be placed. Transabdominal ultrasound is also the modality of choice for evaluating the appendix, so in a female patient with right lower quadrant/pelvic pain, concomitant focused abdominal and pelvic ultrasounds can be performed. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used if more information is needed after ultrasound.

What to Do With an Ovarian Cyst?

Pelvic pain can be caused by an enlarging ovarian cyst, hemorrhage into a cyst, rupture of a cyst, or ovarian torsion caused by a cyst ( Box 9.1 ). In postpubertal females, follicle-stimulating hormone causes one or more Graafian follicles to emerge with a diameter of 1.0 to 2.5 cm in preparation for ovulation. Once an oocyte is released, the Graafian follicle is transformed into a corpus luteum cyst, which remains for 14 days unless the egg is fertilized. If ovulation does not occur and the Graafian follicle continues to enlarge, or if a corpus luteum cyst fails to involute, then a functional/pathological cyst will result. A functional cyst is distinguished from a follicle by size, with follicles measuring less than 3 cm and functional cysts measuring greater than 3 cm. The literature does not indicate a size at which ovarian cysts become symptomatic. There is also controversy regarding the size of an ovarian cyst, and its risk for causing torsion. Some articles cite 5 cm cysts as more likely to be associated with torsion, and some believe that the risk for torsion increases if the cyst is greater than 8 to 9 cm.

Simple ovarian cyst

Hemorrhagic ovarian cyst

Teratoma or other ovarian mass

Ovarian torsion with or without cyst or mass

Paraadnexal cyst

Müllerian anomalies, particularly with obstruction

Isolated fallopian tube torsion

Pelvic inflammatory disease and tuboovarian abscess

Ectopic pregnancy

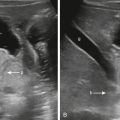

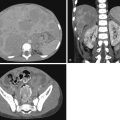

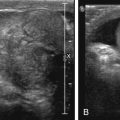

Functional cysts can be simple or hemorrhagic. A simple cyst is unilocular with anechoic fluid. A hemorrhagic cyst occurs as a result of bleeding into a follicular cyst or more often into a corpus luteum cyst. The corpus luteum is lined with thin-walled vessels that can rupture. Most hemorrhagic cysts that are imaged are complex in appearance with a septated fishnet pattern caused by fibrin strands ( Figs. 9.1–9.3 ), fluid–debris levels, or a retracting internal clot ( Figs. 9.4 and 9.5 ). This appearance is thought to represent a subacute cyst, with an acutely hemorrhagic cyst potentially seen as an isoechoic cyst or a cyst with an internal fluid–fluid level. A hemorrhagic cyst can rupture with significant intraperitoneal hemorrhage causing pain with a decline in hematocrit. Blood is then demonstrated within the pelvis as complex free fluid. Hemorrhagic cysts can have a more homogenous appearance, mimicking a solid mass, but with increased through transmission ( Fig. 9.6 ) and acoustic enhancement. A hemorrhagic cyst can be confused with a teratoma or cystic neoplasm, tuboovarian abscess, ectopic pregnancy, or appendiceal abscess. MRI has been suggested to further evaluate the ovarian parenchyma and to distinguish between these etiologies when necessary ( Box 9.2 ).

When ultrasound imaging detects:

Simple ovarian cyst (defined as >3 cm)

Hemorrhagic cyst

Large amount of free fluid within the pelvis suggesting rupture of a simple cyst

Hemorrhagic cyst with echogenic free fluid and decreased hematocrit

Simple and hemorrhagic cysts between 3 and 5 cm should resolve within one to two menstrual cycles and should be followed with ultrasound on days 5 to 10 (follicular phase) of the subsequent menstrual cycle to ensure resolution. Hemorrhagic cysts will become anechoic over time. Ninety percent of cysts spontaneously resolve.

Ovarian cysts larger than 5 cm are less likely to regress, although the majority do regress in 2 to 3 months or two to three menstrual cycles. There are no definite pediatric guidelines for the length of follow-up, although some advocate for allowing 8-12 weeks for resolution. Oral contraceptives for the treatment of functional cysts are not considered to be beneficial. If the decision is made to operate because of size, symptoms, or persistence of the cyst, laparoscopy with excision of the cyst and sparing of the remainder of the ovary is usually recommended. Fenestration of the cyst has a recurrence rate of 5% to 8%. Aspiration is not recommended with a recurrence rate of 33% to 84%.

When to Suspect Ovarian Torsion

Ovarian torsion occurs primarily in adolescents and young women. The classic presentation is severe lower abdominal, pelvic, or groin pain with nausea and vomiting. The pain can be intermittent and recurrent because of torsion and detorsion. Studies have found that fever and white count are less elevated, and pain is more localized with ovarian torsion than with appendicitis. Torsion results when the ovary partially or completely rotates around its vascular pedicle, which first compromises lymphatic and venous flow. The ovary then becomes congested with eventual arterial obstruction and subsequent infarction and necrosis. Adnexal torsion is usually unilateral with 60% of torsions involving the right ovary hypothesized to be caused by the protective nature of the sigmoid colon filling the left pelvis.

Torsion can involve a normal ovary or an ovary associated with a cyst or mass. Torsion of a normal ovary is more likely to occur in the pediatric population than the adult population because of the laxity and elongation of the supporting ligaments in the younger population, which allows increased mobility of the ovary. The uteroovarian ligament, which attaches the ovary to the uterus, shortens with age. A cyst or mass within an ovary can act as a fulcrum causing the ovary to twist upon itself or to swing around its pedicle. The suspensory ligament or infundibulopelvic ligament attaches the ovary to the pelvic sidewall and contains the ovarian vessels. The mesovarium is spread between the ovary and the fallopian tube so that when the ovary twists, the tube may also be involved in the torsion ( Diagram 9.1 ).

It can be difficult to determine whether an ovarian cyst is causing pain primarily or if secondary torsion has occurred, causing the pain ( Fig. 9.7 ). One of the more challenging diagnostic dilemmas occurs when a hemorrhagic cyst or mass occupies the ovary and obscures the normal parenchyma, causing the ovary to appear complex. The differential includes ovarian torsion or a nontorsed ovary containing a hemorrhagic cyst or mass ( Figs. 9.8 and 9.9 ). A complex ovary can also be caused by a tubo-ovarian abscess or rarely an ectopic pregnancy. Often torsion cannot be excluded when a complex ovary is imaged. Clinical presentation may be helpful in determining whether surgery is warranted.

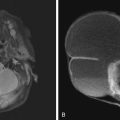

A benign teratoma is the most common ovarian mass associated with torsion ( Box 9.3 ). The presence of a teratoma may cause symptoms without torsion ( Fig. 9.10 ). When a radiograph is obtained for abdominal pain, assessment of the pelvis should include a search for calcifications that may indicate the presence of a teratoma ( Fig. 9.11 ). If pelvic calcifications are present, an ultrasound is performed to confirm a mass and to evaluate the ovary for signs of torsion ( Fig. 9.12 ). By ultrasound, echogenic foci representing calcifications, hair, and fat can be seen within the teratoma. The echogenic foci may appear as a mural nodule or dermoid plug, or as central masses ( Fig. 9.13 ).

Think teratoma with possible ovarian torsion.