Characteristics

Number of patients

Male

26 (37.8 %)

Female

34 (62.2 %)

With 1 mass ablated

53 (88.3 %)

With 2 masses ablated

6 (10.0 %)

With 3 masses ablated

1 (1.7 %)

Mean age ± (SD)

46.0 ± 10.9 years

Number of tumors

68

Mean tumor diameter ± (SD)

36.0 ± 21.3 mm

Diagnosis

Hemangioma

26 (43.3 %)

Focal nodular hyperplasias

9 (15.0 %)

Inflammatory pseudotumor

9 (15.0 %)

Solitary necrotic nodules

8 (13.3 %)

Adenoma

4 (6.7 %)

Angiomyolipoma

3 (5.0 %)

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

1 (1.7 %)

Ablation time ± (SD)

1136.8 ± 837.9 s

Ablation energy ± (SD)

60.8 ± 50.3 kJ

Mean ablation session ± (SD)

1.3 ± 0.5

Mean ablation insertion ± (SD)

2.4 ± 1.4

Mean follow-up month ± (SD)

32.7 ± 20.6 months

The pathological diagnosis was proven in 95.0 % (57/60) of patients with US-guided needle biopsy before ablation, including 23 hepatic cavernous hemangiomas (HCHs), 9 focal nodular hyperplasias (FNHs), 9 inflammatory pseudotumors of the liver, 8 solitary necrotic nodules, 4 hepatic adenomas (HAs), 3 angiomyolipomas, and 1 hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. The other three cases refused biopsy and were confirmed to have HCHs by imaging. Two or three nodules in one person were determined with the same pathological diagnosis because they had similar presentations on contrast-enhanced imaging.

All cases matched at least one of the five indications mentioned above. The liver lesions of 17 patients were uncertain of benignancy and malignancy or doubtful malignancy on imaging. One of the possible reasons for an uncertain diagnosis was atypical imaging features of small lesions. Another one was imaging diagnosis confused by the positive history. Twenty-four nodules enlarged in a follow-up and four had malignant tendency, and 13 patients had symptoms related to occupation of lesions. Sixteen patients complained evidently psychological pressure and mental nervousness because of hepatic lesions detected incidentally, especially in those with positive history.

5.3.2 Ablation Parameters and Curative Effects

Sixty-eight lesions were successfully treated. Average ablated sessions and needle insertions were 1.3 ± 0.5 (one to two sessions) and 2.4 ± 1.4 (one to six insertions) for each lesion, respectively. Average microwave energy and emission time were 60.8 ± 50.3 kJ (range 9–230.4 kJ) and 1136.8 ± 837.9 s (range 180–3,840 s) for every nodule, respectively.

Fifty-five (55/68, 80.9 %) lesions with a maximum diameter of less than and equal to 5 cm and two lesions (2.9 %) with a maximum diameter of more than 5 cm were completely ablated, and no evidence of recurrence was found in the peripheral ablated area (Fig. 5.1).

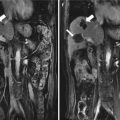

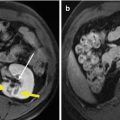

Fig. 5.1

Presentations of a hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma in hepatic segment VIII of a 47-year-old female patient on ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance imaging before and after microwave ablation (MWA). The patient had a history of radical resection of the breast 1 year ago, and the diagnosis of the lesion was doubtfully malignant on enhanced imaging before ablation. The diagnosis was pathologically proven by biopsy under US guidance. (a) Contrast-enhanced US showed the lesion with a maximum diameter of 24 mm slightly peripheral hyper-enhancement and central non-enhancement (arrows) in arterial phase before treatment. (b) Contrast-enhanced US showed the whole lesion non-enhancement (arrows) in portal phase before treatment. (c) Magnetic resonance imaging T2-weighted image showed the ablated lesion mixed signal presentation (arrows) 3 months after treatment. (d) Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showed the ablated lesion non-enhancement (arrows) in arterial phase 3 months after treatment

The ten large HCHs ablated partially showed good results during the follow-up period, and the residual parts had no obvious progress (Fig. 5.2). However, the residual part of the large FNH with a maximal diameter of 56 mm ablated partially continued to grow after 4 months of follow-up because of a new tortuous arterial vessel and was retreated by TAE 18 months after ablation.

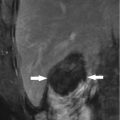

Fig. 5.2

Presentations of a hepatic cavernous hemangioma (HCH) in hepatic segment IV of a 39-year-old female patient on contrast-enhanced computed tomography before and after MWA. (a) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed the HCH peripheral hyper-enhancement (arrows) in delay phase with a maximum diameter of 72 mm before treatment. (b) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed the ablated HCH non-enhancement (arrows) in delay phase 3 months after treatment. Partially unablated areas (arrow heads) close to the middle hepatic vein and inferior vena cava showed no changes compared with those before ablation

The lesion-specific symptoms of the 13 patients (100 %) disappeared or relieved in different degree after ablation. One thing to be mentioned was that the 16 patients (100 %) with evident psychological pressure due to the finding of the hepatic lesion preoperation were relieved of the heavy burden and resumed to normal life.

5.3.3 Side Effects and Complications

According to the definitions of complications and side effects which are consistent with the standardization of terminology and reporting criteria for image-guided tumor ablation [50], side effects are expected undesired consequences of the procedure that, although occurring frequently, rarely, if ever, result in substantial morbidity. These include pain, the postablation syndrome, asymptomatic pleural effusions, minor liver dysfunction in blood serum test, and minimal asymptomatic perihepatic fluid or blood collections seen at imaging. These are not true complications because they do not lead to an unexpected increased level of care.

After MWA of patients with BFLLs, the incidence rates of side effects were similar to the presentations of hepatic malignancy ablation [51]. The body temperature of 44 cases (73.3 %) undulated between 37.2 and 38.5 °C lasting 1–2 days. It was unnecessary to manage it in most patients. Five patients were brought down a fever admitted with the remedy because the body temperature was more than 38.5 °C. According to the common toxicity criteria for reporting pain of the National Cancer Institute, local pain with grade 1 was complained in 55 % (33/60) of all cases, lasting 1–3 days without the drug to relieve. Seven patients complained local pain with grade 2 after ablation as the ablated areas adjacent to the surface of the liver require oral analgesics (oxycodone) and the symptoms gradually disappeared within 1 week. The liver function study showed that serum aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels were increased in 86.7 % (52/60) of all cases. The incremental levels were various, but the highest one was less than three times above the baseline values. Both of these enzymes were normalized in 7 days postoperation. No obvious changes were observed in other serum element levels.

A major complication is defined as an event that led to substantial morbidity and disability, increasing the level of care, or that resulted in a hospital admission or substantially lengthened hospital stay. All other complications were considered minor.

After ablation of BFLLs, the complications of all patients belong to the minor ones. Severe complications such as abscess, bile duct injury, perforation of the gastrointestinal tracts, and hemorrhage requiring embolization did not occur in the perioperative and follow-up periods. Transient hemoglobinuria was found one time in the first urination after therapy in five cases with large HCHs and then resume normal without additional remedy or management. The reason of the occurrence of hemoglobinuria might be a mass of blood cells that were ruined during the ablation of hemangioma in one session.

5.4 Other Nonsurgical Techniques

The clinical reports of nonoperative methods including TAE and RFA were far less than those of surgery, and the number of cases documented was not very large. However, when surgical resection is being considered for BFLLs, the risk of the treatment must be carefully balanced against the benefit of the operation. For those patients in whom resection is impossible or contraindicated because of the location or size of the lesion or other patient factors, nonoperative methods should be considered. Due to minimal invasion, minor morbidity, and satisfying outcomes, the clinical applications of TAE and RFA for successfully treating BFLLs such as HCHs, FNHs, and HAs have been shown as an inspiring prospect.

5.4.1 TAE

In 1991, a clinical literature review summarized that TAE prior to elective hepatic resection should be a good choice to high-risk patients once the HCHs had ruptured [29]. In 2001, a prospective study that evaluated the clinical and radiologic results of TAE for treating symptomatic HCHs was published by Srivastava D. N. et al. [30]. Eight patients (five males and three females) with symptomatic HCHs were treated by TAE with polyvinyl alcohol particles or Gelfoam and steel coils in single session. The largest diameter of the HCHs was 6–18 cm (9.28 ± 5.13 cm). Indications for TAE were abdominal pain (eight patients), rapid tumor enlargement (four of eight), and recurrent jaundice (one of eight). The results showed that the mean size of the tumor did not change significantly; however, symptomatic improvement was documented in all patients after TAE. It was concluded that TAE was a useful procedure in the therapy of symptomatic HCHs. In 2013, a retrospective study to evaluate the effectiveness of small-sized trisacryl gelatin microsphere embolization as a minimally invasive treatment method for patients with symptomatic FNH was reported by Birn J. et al. [34]. Twelve patients (ten women and two men; age range, 18–61 years) with a total of 17 lesions presenting with symptoms of pain were intervened with superselective embolization with 100–300 μm trisacryl gelatin microspheres during the period of 2006–2011. FNH was pathologically proven in 11 lesions from ten patients, and the other lesions exhibited the classic presentation on enhancement imaging for FNH. After TAE, seven patients showed complete relief and five patients showed partial relief of symptoms. Compared with lesion size before the procedure, mean reduction was 61 % (range, 26–90 %) on imaging after TAE 4–10 weeks. Contrast enhancement of lesions was universally decreased after TAE, with 5 of 17 lesions showing no enhancement. Due to the potentiality to malignant change or spontaneous hemorrhage, it was more active to treat HAs clinically. In 2013, a comparative study about resection, embolization, or observation for managing HA was documented by Karkar A. M. et al. [35]. Demographic and outcomes data were retrospectively collected on patients diagnosed with HA from 1992 to 2011. In total, 52 patients (45 females and 7 males) with 100 HAs were divided into single HA (n = 27), multiple HAs (n = 18), and adenomatosis (n = 7) groups. Median sizes of resected, embolized, and observed adenomas were 3.6 cm, 2.6 cm, and 1.2 cm, respectively. Forty-eight HAs were resected as a result of suspicion of malignancy (39 %) or large size (39 %); 61 % of these were solitary. Thirty-seven were embolized for suspicion of malignancy (56 %) or hemorrhage (20 %); 92 % of these were multifocal. Two out of three resected adenomas with malignancy were ≥10 cm and recurred locally (4 %, CI 1–14 %). Ninety-two percent of the embolized adenomas were effectively treated, three persisted (8.1 %, CI 2–22 %). Most observed lesions did not change over time. To draw a conclusion, solitary adenomas were often resected and the multifocal ones were frequently embolized and small ones can safely be observed routinely. Given low recurrence rates, select HAs can be considered for TAE.

5.4.2 RFA

Park S. Y. et al. [38] reported a clinical research about percutaneous US-guided RFA for the management of symptomatic enlarging HCHs to evaluate its feasibility, efficacy, and safety in 2011. Twenty-four patients (5 males and 19 females, with mean age of 49.5 ± 2.2 years old) with 25 HCHs with a diameter of more than 4 cm were treated by percutaneous RFA due to either the presence of symptoms or the enlargement of size compared with the previous imaging studies. The mean diameter of hemangioma was 7.2 ± 0.7 cm (4.0–15.0 cm) with 16 HCHs in the right and nine in the left lobe. Twenty-three HCHs (92.0 %) were successfully treated by RFA. The mean diameter of HCHs was decreased to 4.5 ± 2.4 cm (p < 0.001) in a serial follow-up computed tomography over a mean follow-up period of 23 ± 3.8 months (23–114 months). Symptoms related to HCH disappeared in all successfully treated patients. There were 14 side effects in ten patients including abdominal pain, indirect hyperbilirubinemia (>3.0 mg/dl), fever (38.3 °C), anemia (<10 g/dl), and ascites, which were successfully managed by conservative treatment. It is concluded that percutaneous US-guided RFA is an effective, minimally invasive, and safe procedure for the management of symptomatic enlarging HCH. An exploration to treat HAs using percutaneous RFA was reported by Rhim H. and his colleagues to assess the therapeutic efficacy and safety in 2008 [42]. Ten patients with HA proven pathologically were treated with an internally cooled RF electrode system under US guidance. Eight patients were asymptomatic and two patients had a recurrent tumor after surgical resection. The maximal diameter of the tumors was 2.25 ± 0.76 cm (range: 1.5–4.5 cm). All patients tolerated well the percutaneous RFA procedure without any incident. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (n = 7) or US (n = 3) obtained immediately (<24 h) after the procedure revealed complete ablation of the tumor in all cases. There was no case of local tumor progression or new recurrence during the 2–35 months’ (mean, 17.5 months) follow-up period. Neither procedure-related mortality nor major complication requiring specific treatment was observed. It is concluded that percutaneous RFA can be a new potential alternative therapy for HA without overt complication.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree