The paradox of the increased use of imaging without obvious evidence of improved health outcomes has led to calls for payment based on value rather than volume. Measurement of radiologists’ performance is a key component of the measurement of value. The paradigm shift occurring in radiology and health care as a whole may seem daunting to the radiologist with the clamor for increasing accountability from payers and patients alike. However, it is through powerful tools such as performance measures in radiology and their accompanying incentive-based payment systems that practices can be improved and confidence of patients restored.

- •

Physician performance can be measured objectively.

- •

There is a Government mandate to promote quality and efficient delivery of health care to help contain costs and cut waste. Physician performance is a key part of this effort.

- •

Objective criteria for physician performance have an influence on payment.

- •

Performance standards for neuroradiology have been developed.

- •

Outcome, process, structure, and satisfaction are domains of performance measurement.

- •

It is important to account for bias as well as adverse and unintended consequences.

- •

Health care can be improved by application of objective standards.

- •

Performance measures, when applied successfully, can objectively validate the trust of the public and payers in the care delivered by physicians and neuroradiology as a whole.

It is the purpose of this order to ensure that health care programs administered or sponsored by the Federal Government promote quality and efficient delivery of health care through the use of health information technology, transparency regarding health care quality and price, and better incentives for program beneficiaries, enrollees, and providers. —Executive Order of the President, August 26, 2006.

The problem

It has long been a fundamental principle of management that you can only manage what you can measure. This dictum is now finding application in the arena of physician and health system payment reform. The issue is no longer whether radiologists’ performance will be measured; that is a given. The questions that remain are how and by whom. Another question is whether good performance will be rewarded or bad performance punished, and what will be the nature of the bonus or malus. Just as consumers of other products demand objective measures of quality, so consumers and their surrogates are demanding that the health care system deliver demonstrable quality. None of us would buy a car without consulting some objective authority regarding the performance parameters we value. Reliability, safety, and economy are considered basic criteria for these judgments, and we certainly take subjective factors such as style, handling, and performance characteristics into account. Consumers of health care, via their surrogates such as insurance companies, and payers such as employers and taxpayers, through their representatives in government, demand nothing less of us.

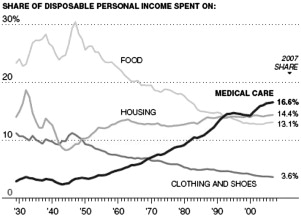

The public recognizes both the importance and the high cost of imaging. Most concerns revolve around cost and quality, or as President George W. Bush succinctly put it, “transparency regarding health care quality and price.” Much of this concern is fueled by the startling growth of health care costs in the United States over time, from around 3% of gross domestic product (GDP) in the 1940s to 17.3% in 2009 while the relative cost of other goods and even some services has declined ( Fig. 1 ).

It is also relevant that the United States system, in the aggregate, produces worse results at higher costs than those of other countries. Indeed, the debate on cost control in radiology closely mirrors that of the global health care debate in this country.

Equally compelling is the question of utilization. Radiology especially has become a target of utilization review, given the steep climb in recent years in quantity and costs of expensive imaging tests and procedures. We are asked: are all the tests being performed really necessary? The paradox of increased use without obvious evidence of improved health outcomes has led to calls for payment based on value rather than volume. Measurement of radiologists’ performance is a key component of the measurement of value.

The framework

Pay for performance is defined as any payment scheme that explicitly tries to align the incentives of the provider with that of the patient; this has not always been the case in the past. For example, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission in 2003 stated “the Medicare payment scheme is largely neutral or negative toward quality… At times providers are paid even more when quality is worse, such as when complications occur as a result of error.” In a fee-for-service environment, volume is rewarded while quality is not, except in those circumstances whereby high-quality providers capture a greater market share as a result of their reputation for excellence.

Defining performance and quality, and setting up a feasible scheme for aligning quality with payment, have therefore become a central component in the health care debate, given the growth of health care spending in absolute as well as relative terms as a share of GDP, and the attendant questions regarding use and effectiveness.

Primary assumptions for the theoretical development of performance measures include the following:

- 1.

Medical doctors are human from a management standpoint.

- 2.

As humans, they respond to incentives.

- 3.

Patients and/or their surrogates need information to make choices.

- 4.

Health care, and radiology within this framework, is a rational enterprise.

Rational decision makers will choose the highest quality at the best price. The introduction of management techniques has been shown to increase productivity and reduce cost in other enterprises. Assuming that health care and thus radiology are rational human enterprises, it can be postulated that application of effective management techniques to health care and thus radiology can also improve productivity and reduce cost and waste. Indeed this has been shown to be the case, as pay-for-performance measures, even with small incentives, have been shown to improve quality of care in comparison with control groups.

The reference point for performance measurement can also be controversial. Under the standard medical paradigm of care, we try to establish a single threshold for risk versus benefit for an intervention. Once this is reached, the doctor suggests the intervention. In a more patient-centered world, several thresholds may exist. These thresholds would include one under which no intervention would take place, an intermediate zone where undergoing the intervention is left to the patient’s discretion, and a third threshold where an intervention is clearly recommended. Such a scenario is important because physicians and patients differ systematically in the perception of risk, especially when domains of disability are not the same. For example, in a study by Guyatt and colleagues, physicians and patients differed widely regarding how many gastrointestinal bleeds they were willing to tolerate to prevent a stroke. Thus, the discretionary range may be quite large, or the thresholds may be set via social consensus at cutoff points that seem puzzling to technically oriented physicians. Finally, interventions based on principles of evidence-based medicine yield better outcomes at reduced cost than non–evidence-based practices.

Central to pay for performance is performance itself. How do we measure this? How do we rationally develop a methodology to measure and reward performance in radiology?

The framework

Pay for performance is defined as any payment scheme that explicitly tries to align the incentives of the provider with that of the patient; this has not always been the case in the past. For example, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission in 2003 stated “the Medicare payment scheme is largely neutral or negative toward quality… At times providers are paid even more when quality is worse, such as when complications occur as a result of error.” In a fee-for-service environment, volume is rewarded while quality is not, except in those circumstances whereby high-quality providers capture a greater market share as a result of their reputation for excellence.

Defining performance and quality, and setting up a feasible scheme for aligning quality with payment, have therefore become a central component in the health care debate, given the growth of health care spending in absolute as well as relative terms as a share of GDP, and the attendant questions regarding use and effectiveness.

Primary assumptions for the theoretical development of performance measures include the following:

- 1.

Medical doctors are human from a management standpoint.

- 2.

As humans, they respond to incentives.

- 3.

Patients and/or their surrogates need information to make choices.

- 4.

Health care, and radiology within this framework, is a rational enterprise.

Rational decision makers will choose the highest quality at the best price. The introduction of management techniques has been shown to increase productivity and reduce cost in other enterprises. Assuming that health care and thus radiology are rational human enterprises, it can be postulated that application of effective management techniques to health care and thus radiology can also improve productivity and reduce cost and waste. Indeed this has been shown to be the case, as pay-for-performance measures, even with small incentives, have been shown to improve quality of care in comparison with control groups.

The reference point for performance measurement can also be controversial. Under the standard medical paradigm of care, we try to establish a single threshold for risk versus benefit for an intervention. Once this is reached, the doctor suggests the intervention. In a more patient-centered world, several thresholds may exist. These thresholds would include one under which no intervention would take place, an intermediate zone where undergoing the intervention is left to the patient’s discretion, and a third threshold where an intervention is clearly recommended. Such a scenario is important because physicians and patients differ systematically in the perception of risk, especially when domains of disability are not the same. For example, in a study by Guyatt and colleagues, physicians and patients differed widely regarding how many gastrointestinal bleeds they were willing to tolerate to prevent a stroke. Thus, the discretionary range may be quite large, or the thresholds may be set via social consensus at cutoff points that seem puzzling to technically oriented physicians. Finally, interventions based on principles of evidence-based medicine yield better outcomes at reduced cost than non–evidence-based practices.

Central to pay for performance is performance itself. How do we measure this? How do we rationally develop a methodology to measure and reward performance in radiology?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree