and Alfredo Blandino1

(1)

Department of Radiological Sciences, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

Crohn’s disease is commonly complicated by a variety of perianal manifestations. Perianal fistulas and abscesses can result in substantial morbidity, including scarring, continual seepage, and fecal incontinence [1].

Perianal abscess occurs in up to 80 % of patients with CD [2], as the frequency of perianal fistulas varies from 17 to 43 % [3–9]. A distal involvement of the gastrointestinal tract increases itself the incidence of perianal manifestations. In fact, patients with disease confined to the colon have a higher incidence of perianal fistulas, and their rate of incidence approaches 100 % in patients with CD that involves the rectum [4, 10].

For what concerns the pathogenesis of perianal abscess, it may result from a cryptoglandular infection or an obstructed sinus tract [1].

The exact pathogenesis of perianal fistula is instead unidentified. The first theory suggests that fistulas may be due to the elongation of deep penetrating ulcers in the anus or distal rectum; over time, feces collect in these ulcers, and the pressure of evacuation forces the fecal matter into the subcutaneous tissue, extending the ulcer and creating fistula [1, 11]. The second theory suggests that fistulas result from an anal gland abscess that serves as the point of origin for a fistulous tract; the complexity of fistula that follows depends on the type of abscess drained [12].

Perianal CD may herald the development of intestinal manifestations by several months to several years. About two-thirds of patients with perianal disease will be diagnosed with intestinal disease within 1 year and another third within 1–5 years, with only a few patients being diagnosed after more than 5 years. Only a small proportion of patients with Crohn’s disease may persist in having isolated perianal involvement [13, 14].

Surgical management of perianal CD depends on the extent of the primary fistula and of any secondary fistulous tracks or associated abscesses, being usually more aggressive with larger fistulas and conservative in the case of smaller lesions. Consequently, an accurate preoperative classification with adequate imaging techniques is required to clearly identify the fistula and its intra- and extrasphincteric extent and, as far as possible, to avoid aggressive procedures and/or recurrences that may result from any undiagnosed secondary branches.

Moreover, preservation of fecal continence is the principal consideration, and all treatment strategies should aim to preserve the integrity of the external sphincter.

6.1 Classification of Fistulas

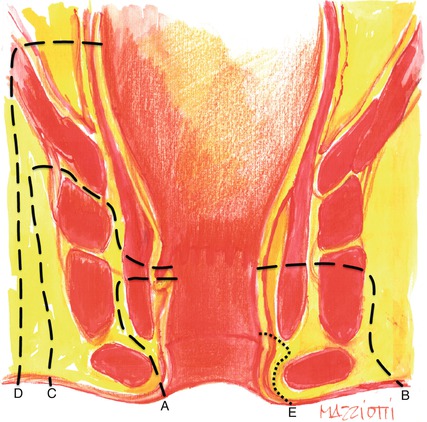

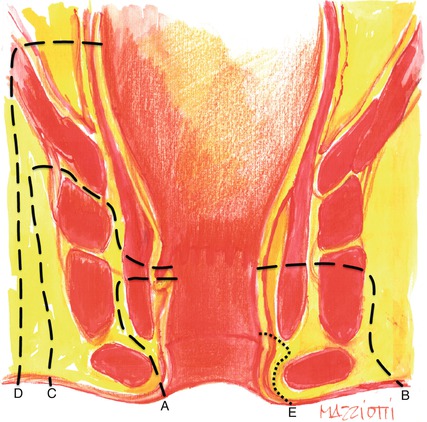

Classification systems for perianal fistulizing disease are useful in determining what surgical procedure (if any) should be performed. Several classifications have been used to define the different types of fistulas. The most anatomically detailed classification system, and the most widely used, is that one formulated by Parks and his colleagues; it encompasses the external anal sphincter as anatomical landmark, and with reference to the coronal plane, it distinguishes four different kinds of fistula: intersphincteric, trans-sphincteric, supra-sphincteric, and extrasphincteric (Table 6.1) [15]. A superficial, subcutaneous fistula, instead, has no relation to the sphincter or the perianal gland and therefore is not part of the Parks’ classification (Fig. 6.1).

Intersphincteric: within the intersphincteric space, between the internal and external sphincters |

Trans-sphincteric: extends through both the internal and external sphincters |

Supra-sphincteric: from the skin surface to the ischiorectal fossa, without communication with the anal sphincter |

Extrasphincteric: above the levator ani muscle, within the pelvic region |

Fig. 6.1

Parks’ classification (for anatomical correlation, see Fig. 3.6): A intersphincteric fistula, B trans-sphincteric fistula, C supra-sphincteric fistula, D extrasphincteric fistula, E subcutaneous fistula (not part of Parks’ classification)

More recently, new MR imaging-based classifications have been proposed, such as the classification of St. James Hospital [16]. It consists of five grades and relates the Parks’ surgical classification to MRI anatomy seen on both axial and coronal planes (Table 6.2) [16].

Grade 0 | Normal aspect |

Grade 1 | Simple linear intersphincteric fistula |

Grade 2 | Complex intersphincteric fistula with abscess or secondary track |

Grade 3 | Trans-sphincteric fistula |

Grade 4 | Trans-sphincteric fistula with abscess or secondary track within the ischioanal or ischiorectal fossa |

Grade 5 | Supralevator and translevator fistula |

6.2 MRI in Perianal CD

The role of imaging in perianal complications of CD is to identify the primary fistulous track, even in the absence of cutaneous openings, the possible secondary tracks, and the sites of any abscess cavities, and to define their relations with the sphincters, the levator ani muscle, and the ischiorectal and ischioanal fossa [17].

As mentioned in Chap. 1, MRI performed along the coronal and axial planes demonstrates fistulous tracks in relation to the sphincteric complex, ischiorectal and ischioanal fossae, and levator plate.

Tracts are described in accordance with the terminology illustrated by Parks et al. [15].

In particular, in order to describe the exact site and direction of fistulous tract according to the surgical view, radiologist should correlate the axial MRI findings to the “anal clock.”

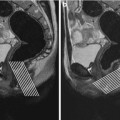

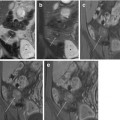

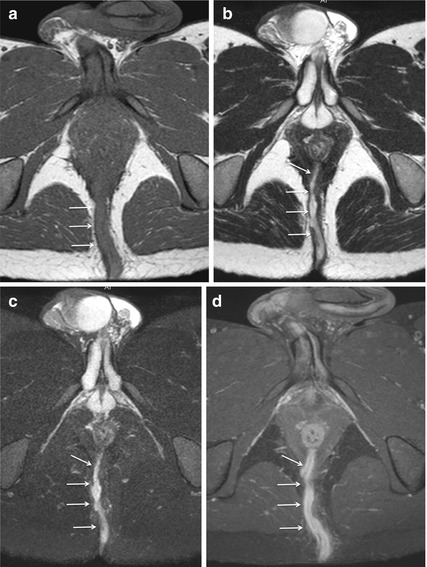

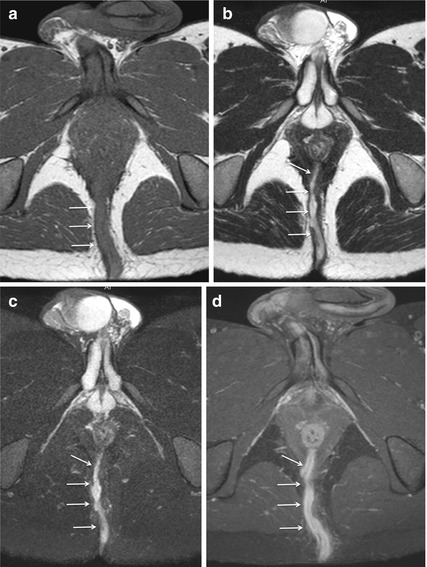

Abscesses and active tracts filled with pus and granulation tissue appear as hyperintense structures on T2-weighted and STIR images (Figs. 6.2, 6.3, and 6.4). In particular, identification of the tract is most easily performed on fat-saturated sequences, whereas the T2-weighted sequences without fat suppression give more detailed information about the relationship of the tract with surrounding anatomical structures (Fig. 6.5).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Fig. 6.2

Trans-sphincteric fistula. Axial-oblique T1-weighted TSE (a) and T2-weighted TSE images, performed without (b) and with fat saturation (c), show a posterior midline trans-sphincteric fistula, hypointense on T1-weighted image, and hyperintense on T2-weighted images (arrows

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree