Fig. 22.1

A 60 year-old male, known to have severe peripheral vascular disease with chest pain. There is a focal outpoutching from the aortic arch (arrow) with overhanging edges in keeping with a penetrating ulcer

The natural history of penetrating aortic ulcers is uncertain. Asymptomatic patients may have atheromatous aortic lesions that are indistinguishable from PAU. Hence, most units tend to take a conservative treatment approach. Persistent pain, hemodynamic instability or aortic rupture requires active intervention either by surgery or endovascular stent graft placement.

Intramural Hematoma (IMH)

IMH accounts for 10–20 % of AAS and is characterized by rupture of the aortic vasa vasorum and extravasation of blood into the intramedial or subadventitial compartments either spontaneously or secondary to blunt trauma. Unlike dissection, there is no entrance tear and the process is confined within the aortic wall with no direct communication with the aortic lumen.

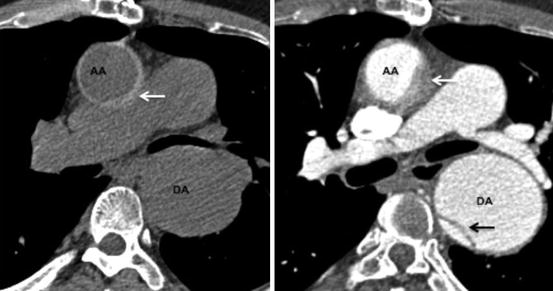

An unenhanced CT dataset is very valuable in the diagnosis of IMH. The fresh thrombus will be seen as a crescent shaped or circular thickening of the aortic wall (>7 mm). The thrombus will appear hyperdense (Hounsfield unit 60–70) compared to the unenhanced blood. This smooth area will not show any enhancement on the subsequent CT with intravenous contrast medium and there will be no demonstrable intimal flap (Fig. 22.2). IMH can also be differentiated from mural thrombus by luminal displacement of the calcified intima in the former whilst the latter lies outside the calcification.

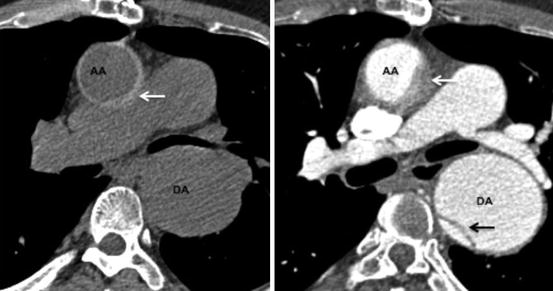

Fig. 22.2

A 70-year old hypertensive male with acute chest pain. Left panel is unenhanced axial CT image demonstrating crescentric high attenuation (arrow) in the ascending aorta (AA). Right panel is the corresponding post IV contrast medium image with non-enhancing intramural hematoma (arrow). The descending aorta (DA) is aneurysmal and has a focal dissection flap (black arrow)

IMH is a dynamic process and has a variable clinical course with regression seen in about 10 % of cases. There seem to be differences in the natural history between Asian and Caucasian patients. In the western population, IMH involving the ascending aorta (type A-IMH) has a greater risk of rupture or dissection.

Another acute complication of IMH is the development of saccular pseudoaneuysms, commonly in the distal aortic arch. Many studies have established predictive factors for IMH progression that include a Type A location, maximal aortic diameter of greater than 50 mm, IMH thickness greater than 16 mm and severe luminal compromise. The presence of significant pleuro-pericardial effusions, penetrating ulcers and persistent pain are other perilous signs.

Aortic Dissection (AoD)

Dissection is the most common cause of AAS. Acute dissection generally occurs within 14 days of onset of pain. Dissection is the result of intimal laceration and longitudinal splitting of the aortic media, giving rise to an entrance tear and an intimomedial flap forming a double-barrel aorta. The blood-filled space within the delaminated medial layer is the false lumen.

The Stanford classification divides the dissection in to Type A for ascending aortic involvement and Type B for intimal tears of descending aorta distal to left subclavian artery. However, arch dissection without involvement of the ascending aorta is also labeled as Type B. An alternative classification is the DeBakey system based on the origin of the intimal tear and the extent of the dissection. A Type I tear originates in the ascending and propagates to the arch and descending aorta. Type II is confined to the ascending aorta. Type IIIa is limited to descending thoracic aorta whilst Type IIIb propagates distally below the diaphragm (Fig. 22.3).

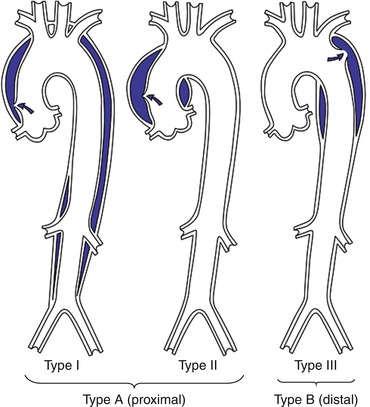

Fig. 22.3

DeBakey and Stanford classification of aortic dissection (Used with permission from Larsen R. Thorakale Aortenaneurysm. Heidelberg: Springer Science+Business Media, 2012)

Chest radiograph may show mediastinal widening, abnormal aortic and cardiac contours, displacement of aortic calcification and pleuro-pericardial effusions. It is important to remember that a chest x-ray cannot exclude the presence of aortic dissection, as it may be normal in up to 40 % of patients.

CT is invaluable in delineating the extent of dissection, branch vessel involvement and evaluation of end organ damage and associated complications. The addition of ECG gating to image acquisition helps eliminating false positive diagnoses of mural flaps in the proximal aorta, particularly the aortic root, which can occur as a result of a motion artifact. In addition, gated studies allow for assessment of coronary arteries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree