Fig. 20.1

The mal-positioned endotracheal tube tip is within the right main bronchus (block arrow) with resultant collapse of the left lung

Trauma to the trachea from tube placement may lead to glottis and tracheal edema, and in extreme cases rupture. On CXR, the trachea should maintain smooth lateral margins as bulging may represent over-dilatation or tracheal wall edema. A chest radiograph following tracheostomy placement has to be scrutinized for the presence of mediastinal hematoma, which may be seen as widening of the mediastinum on CXR, and presence of mediastinal air.

Mechanical Ventilation

Mechanically ventilated patients are unable to clear respiratory tract secretions and are therefore at higher risk of mucus plugs, which lead to areas of lung collapse. Mechanical ventilation can cause barotrauma and patients may develop pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, surgical emphysema or interstitial emphysema.

Nasogastric Tubes

These are commonly placed in ICU patients for nutritional or drainage purposes. Nasojejunal tubes are placed in patients with poor pyloric function. The nasogastric tube tip should lie below the left hemi-diaphragm, distal to the gastro-esophageal junction with all the side holes within the stomach. Malposition of the tube within the bronchi must be recognized when reviewing the plain film in order to avoid administration of medication and fluids into the lungs (Fig. 20.2). It has to be remembered that in some critically ill patients the stomach may be displaced in the thoracic cage and above the diaphragm. In these cases plain AP and lateral X-ray can easily diagnose the problem.

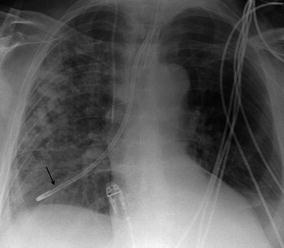

Fig. 20.2

The malpositioned nasogastric tube lies within the right main bronchus (arrow) and requires immediate repositioning. Patchy air space shadowing within the right lung reflects aspiration pneumonia

Central Venous Lines

Indwelling catheters for monitoring and drug administration purposes should be positioned so that the tip is in the proximal SVC. Pulmonary artery catheters should lie with the tip in the proximal pulmonary artery. Invasive lines carry an associated risk of pneumothorax or hemothorax, which usually occur during insertion, and these complications should be looked for on the post-procedural plain film. Associated pneumomediastinum imposes as lucency surrounding the mediastinum and a continuous diaphragm visible on CXR (Fig. 20.3), while surgical emphysema can be seen as air within the soft tissues. Invasive lines are also a potential source of septic emboli, which may be seen on CXR as multiple irregular opacities with central cavitation.

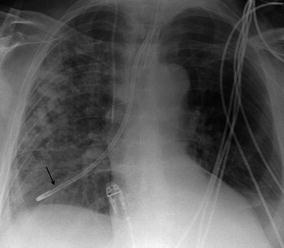

Fig. 20.3

An endotracheal tube, nasogastric tube and right internal jugular line are in situ. There is increased lucency around the heart and mediastinum (black arrows) in keeping with a pneumomediastinum. The left lung appears more lucent than the right in the supine position, suggesting an associated pneumothorax. There is subcutaneous emphysema seen in the left supraclavicular region and the left chest wall (white arrows)

Central line malposition is easily diagnosed on plain radiography. Inadvertent carotid cannulation, carotid and jugular antegrade position, migration into contralateral jugular vein position have all been described. It is important to remember that the malpositioned venous catheter in a large vein could still be used for sampling, monitoring, and drug infusions.

Pulmonary artery catheters are also easily visualized on plain radiography. The complications associated with these are divided into complications with central venous cannulation (common to other central venous access), malposition (right atrium, right ventricle), pulmonary artery rupture and formation of a false aneurysm (Fig. 20.4). If the pulmonary artery rupture is non-fatal a CXR is likely to demonstrate opacification around the affected pulmonary artery, representing a combination of pulmonary hemorrhage and pseudoaneurysm.

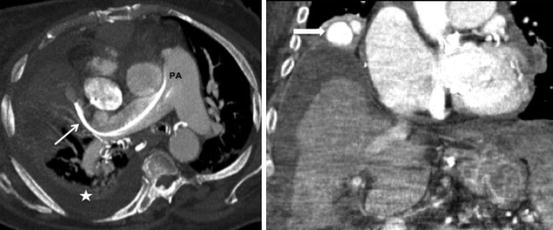

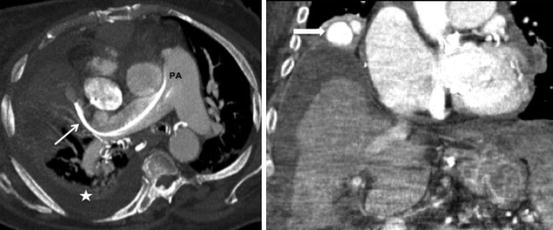

Fig. 20.4

(Left) The Swan Ganz catheter tip is too distal and lies within the segmental pulmonary artery (PA) (thin arrow). Right pleural collection (star). (Right) The patient went on to develop pulmonary artery aneurysm (block arrow)

Chest Drains

Drains may be inserted to treat pleural collections of fluid, pus, blood or air. The optimal position of the drain tip within the pleural space depends on the underlying pathology – usually superiorly for a pneumothorax and inferiorly for fluid collections. All side holes have to be within the space, and a poorly positioned tube may lead to failed drainage and continued symptoms. Chest drain insertion may lead to a hemothorax if an intercostal vessel is damaged during insertion. Typically an extrapleurally contained hematoma of varying size can be found.

Malposition of chest drains is not uncommon. It includes pulmonary intraparenchymal, intraesophageal, intracardiac, intraperitoneal, intrahepatic, transgastric, and extrapleural location. Malposition is usually readily diagnosed on CXR but some patients may require CT. Using image guidance or insertion by an experienced operator reduces the prevalence of such malposition.

Hypoxia Related to Pleural Disorders

Pneumothorax

This is one of the most frequently encountered pathologies when reviewing chest radiographs of ICU patients. The term pneumothorax refers to free air in the pleural space. Air may be introduced by leakage from the lung, or breach of the chest wall from an external source. Imaging features suggestive of tension pneumothorax are described in Chap. 19.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree