PETROUS APEX BENIGN NEOPLASMS AND SLOW-FLOW VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography can almost always make a reasonably definitive diagnosis of a benign tumor of the petrous apex.

- Imaging is essential in initial treatment planning and following surveillance strategies depending on the extent of disease and approach to treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Etiology

Benign neoplasms of the petrous apex are uncommon. Slow-flow vascular malformations are even more uncommon but are considered in this chapter because their growth pattern most commonly resembles that of a benign or at least very low grade tumor. Vascular malformations and tumors essentially arise from the tissues of the region and must be differentiated from the relatively short list of mucosal, congenital, other vascular and malignant diseases that affect this part of the postero lateral portion of the central skull base. There is naturally considerable overlap with the same or similar conditions affecting the cavernous sinus that are discussed in Chapters 72 through 75. The most common of these discussed in this chapter are meningiomas and nerve sheath tumors. Chordomas (Chapter 34), chondrosarcomas (Chapter 39), and paragangliomas (Chapter 33) are discussed separately. Other benign tumors are rare and include lesions of mesenchymal and osseous origin such as fibromyxomas and osteochondromas and even pituitary tumors discussed in Chapters 32 and 35 through 40.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

These are mainly sporadic tumors, usually with no known predisposing conditions. Patients with neurofibromatosis types I and II and mosaics of those conditions are far more likely than the general population to have a nerve sheath tumor and are at increased risk for meningioma.

Clinical Presentation

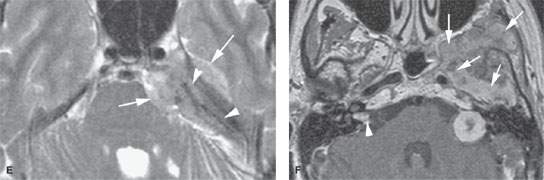

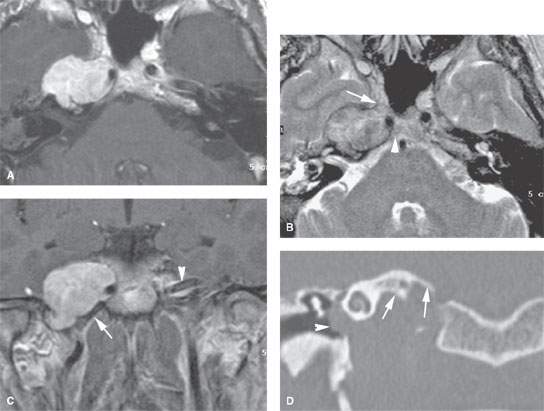

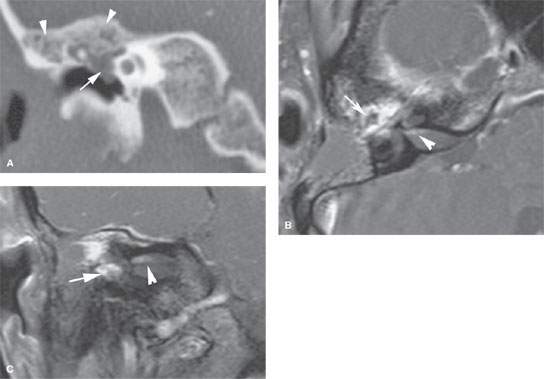

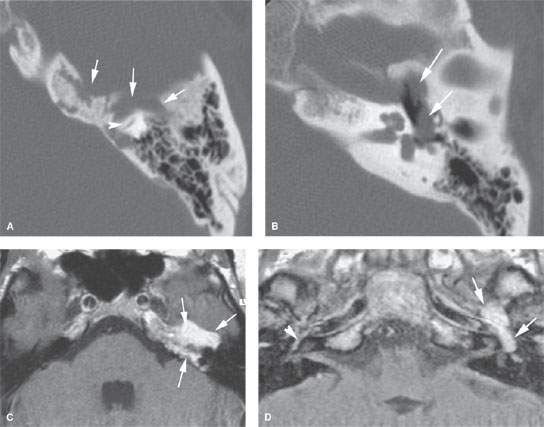

Facial, periorbital, and periocular pain or other mainly trigeminal- and abducens nerve–related dysfunction occurs when the mass involves the mesial aspect of the petrous apex at its interface with entrance of the trigeminal nerves to its cistern (Figs. 124.1 and 124.2). Dural involvement can produce localized headaches that most typically produce otalgia and/or are retro-orbital or referred to the skull vertex similar to the pattern of sphenoid sinus referral patterns. A mass situated more laterally in the internal auditory canal or at the first genu/geniculate ganglion may result in facial paralysis (Figs. 124.3 and 124.4). Hearing loss may be conductive due to eustachian tube obstruction or impingement on the ossicles (Figs. 124.2D and 124.4). Sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo, and/or tinnitus may be due to cochleovestibular nerve or direct inner ear involvement. Cranial nerve deficits tend be grouped as VII through XII and II through VI depending on the site of origin and extent of the mass, although the deficits are typically of only one or two nerves at the time of presentation—most commonly, cranial nerves V and VI (Figs. 124.1 and 124.4). Carotid artery occlusion can lead to signs and symptoms of ischemia but is rarely, if ever, associated with these lesions at presentation.

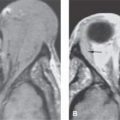

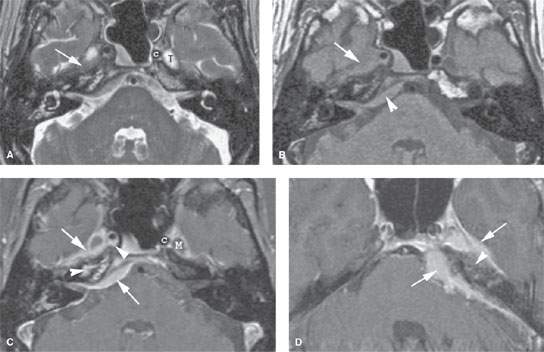

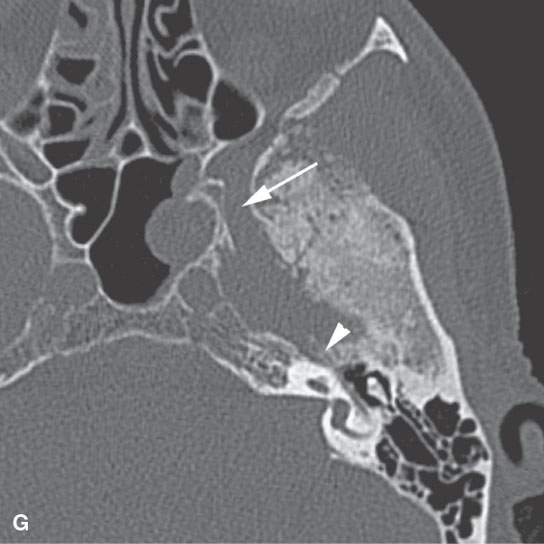

FIGURE 124.1. Three patients with a meningioma of the petrous apex. A–C: Patient 1 presenting with ophthalmoplegia. A dural mass (arrows), isointense to brain tissue on T2-weighted (A) and T1-weighted (T1W) (B) images with homogeneous intense enhancement (C), is seen along the anterior and posterior dural surfaces of the petrous apex and the clivus. The changes in the petrous apex air cells likely are due to reactive mucosal disease based on the high signal intensity in (A) and inflammatory changes in the right mastoid. However, there is limited intraosseous spread in the petrous apex and extension to the trigeminal cistern (T), encroachment and narrowing of the cavernous carotid artery (C), and growth into the sphenoid sinus (arrowheads in C). Within the internal auditory canal and along the posterior fossa, a dural tail—either due to tumor or reactive changes—is present. D, E: Patient 2 presenting with ophthalmoplegia and facial pain. This petrous apex meningioma had very extensive intraosseous (arrowheads) and extraosseous (arrows) components in contrast to that found in Patient 1 with a mainly dural spread pattern. F, G: Patient 3. A small number of petrous apex meningiomas are related to syndromes such as neurofibromatosis type 2. Postcontrast T1W magnetic resonance (F) shows a diffuse dural mass in the middle fossa with intraosseous and extracranial extension associated with bilateral vestibular schwannomas. On computed tomography (G), thickening and hyperostosis with preserved trabecular architecture of the adjacent bone due to the proven meningioma is seen from the geniculate ganglion region (arrowhead) to the foramen rotundum. The margins of both the inner and outer table of the skull bone are irregular.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anatomy

The anatomy of interest is that of the petrous apex (Figs. 104.15–104.17) and mastoid air cell tract development as those air cells populate the petrous apex, which is described in detail in Chapter 104 (Fig. 104.48). It is also useful to understand the relationship of cranial nerves V and VI to the petroclival fissure region and the petrous segment of the carotid canal (Fig. 112.2). Collateral knowledge about the entire temporal bone and related cranial nerves is also a general requisite for interpreting studies of patients with petrous apex masses.

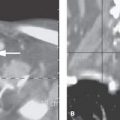

FIGURE 124.2. Nerve sheath tumor at the petrous apex. The patient presented with facial pain, ophthalmoplegia, and hearing loss. A–C:Magnetic resonance study. In (A), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image shows a homogeneously enhancing mass centered at the right petrous apex with extension toward the cavernous sinus and displacement of the internal carotid artery. In (B), the T2-weighted image shows the mass to be of mixed signal intensity, generally in the range of gray and white matter. There was extension to the region of the trigeminal cistern (arrow) and the region of the Dorello canal. These findings explain the ophthalmoplegia and facial pain. In (C), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted coronal image shows the transcranial extension of the mass and related displacement of the carotid artery from the carotid canal (arrow) compared to the normal position of the opposite carotid canal (arrowhead). D: Coronal computed tomography image showing the well-circumscribed mass undermining the petrous apex with smooth regressive remodeling of bone (arrows) and the mass protruding into the middle ear, explaining the conductive hearing loss noted clinically.

FIGURE 124.3. A patient complaining of facial paralysis, hearing loss, and tinnitus. A: On computed tomography, reactive but nonspecific hyperostosis of the tegmen tympani is seen (arrows), and there is a nonspecific-appearing middle ear mass. B, C: After an exploratory mastoidectomy, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images were taken and show the en plaque meningioma along the tegmen tympani and anterior border of the petrous bone with intraosseous and middle ear extension, encroaching the ossicular chain without eroding it (arrow). Some dural enhancement is seen in the fundus of the internal auditory canal (arrowhead). (NOTE: Had magnetic resonance imaging been done preoperatively, the diagnosis likely could have been anticipated and the “surprise” at surgery avoided.)

Pathology and Patterns of Disease

The appearance, patterns of growth, and pathophysiology of benign tumors in general are discussed in Chapter 21; those of nerve sheath tumors and meningiomas are discussed more specifically in Chapters 29 and 31, respectively. Slow-flow vascular lesions (Fig. 124.5), commonly referred to as hemangiomas when they affect the temporal bone, are discussed in Chapter 9.

These solid and often homogenously well-vascularized benign tumors may compress cranial nerves V, VI, VII, and VIII and become adherent to major vessels including the dural sinuses, carotid artery, and jugular vein (Figs. 124.1 and 124.2). Involvement of these transiting structures may be associated with obvious remodeling of the internal auditory canal, carotid canal, and jugular fossa. The otic capsule bony and membranous labyrinth may eventually be involved (Figs. 124.3 and 124.4). Petroclival meningiomas arise from the arachnoid villi of the clivus or the mesial petrous apex. Meningiomas may be largely intraosseous; however, most grow in an exophytic manner along the dural surfaces (Figs. 124.1 and 124.3).

Schwannomas of the petrous apex typically arise from cranial nerves V, VII, and VIII (Figs. 124.2 and 124.4). Sometimes, large schwannomas from the lower cranial nerves may grow into the apex.

Slow-flow vascular malformations will generally have a narrow zone of transition in bone with the telling sign of a stippled or lacy calcification pattern within the interstices. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) pattern is predictable but nonspecific (Fig. 124.5).

Pathologically Altered Function

Typically, there are no deficits created early in the pathogenesis of these chronically progressive tumors. At some point, the bony eustachian tube may be compressed with resulting middle ear disease, most commonly otitis media with effusion. Extensive lesions can cause compressive cranial neuropathies and inner ear dysfunction.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

Specific protocols for computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) studies for investigating petrous apex masses appear in Appendixes A and B. These are typically studied with dedicated contrast-enhanced imaging of the temporal bone. Computed tomographic angiography and MR angiography are included as necessary. Diagnostic catheter angiography is commonly done as a prelude to endovascular interventions or occasionally to confirm the diagnosis.

Pros and Cons

MRI provides a definitive diagnosis when typical morphologic features and growth patterns of the mass are expressed on various pulse sequences. Differentiation from all other petrous apex pathology is relatively simple based on the MRI findings (Figs. 124.1–124.5). MRI is typically preferred for posttreatment surveillance.

FIGURE 124.4. A patient presenting with facial nerve weakness and otalgia. This was eventually proven to be due to a schwannoma involving the petrous apex. A, B: Computed tomography study showing an erosive but nonreactive bony pattern along the petrous apex (arrows) that extends to involve the otic capsule bone (arrowhead). In (B), the mass protrudes into the middle ear cavity, explaining the conductive hearing loss. C, D: Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images showing the mass. In (C), the mass involves the petrous apex and is homogeneously enhancing. This image correlates to that in (A) (arrows). In (D), to correlate with (B), the lobulated enhancing mass extends into the middle ear and occupies the region of the geniculate ganglion, explaining both facial nerve weakness and conductive hearing loss. Compare this to the normal amount of enhancement seen at the anterior genu (arrowhead) on the opposite side.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree