PETROUS APEX CHONDROSARCOMA

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography can almost always suggest the proper diagnosis of a benign tumor of the petrous apex.

- Imaging is essential in initial treatment planning and following surveillance strategies depending on the extent of disease and approach to treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Etiology

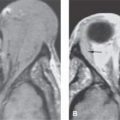

Chondrosarcomas of the petrous apex are uncommon; however, they are the most common primary malignant tumor of the petrous apex. There is some propensity for even more benign osteochondral lesions (Fig. 125.1A,B) to involve the petrous apex often near the petroclival junction. Chondrosarcomas are discussed in general in Chapter 39 and more specifically as they relate to the various lesions that affect the petrous apex in this chapter. Chondrosarcomas must be differentiated from the relatively short list of mucosal, congenital, vascular, and benign and malignant tumors that affect this part of the posterolateral portion of the central skull base. The most common of the benign tumors are meningiomas and nerve sheath tumors discussed in Chapter 124. Chordomas (Chapter 34) and paragangliomas (Chapter 33) are discussed separately. Other benign tumors are rare and include mesenchymal- and osseous-origin lesions such as fibromyxomas and osteochondromas and even pituitary tumors discussed in Chapters 32 and 35 through 40.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

These are mainly sporadic tumors usually with no known predisposing conditions.

Clinical Presentation

Facial, periorbital, and periocular pain or other mainly trigeminal nerve–related dysfunction occurs when the mass involves the mesial aspect of the petrous apex at its interface with entrance of the trigeminal nerves to its cistern. Diplopia has been reported to be a predominant presenting symptom.1,2 Dural involvement can produce localized headaches that most typically produce otalgia and/or headaches that are retro-orbital or referred to the skull vertex similar to the pattern of sphenoid sinus referral patterns.

A mass situated more laterally in the internal auditory canal or at the first genu/geniculate ganglion may result in facial paralysis. Hearing loss may be conductive due to eustachian tube obstruction. Sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo, and/or tinnitus may be due to cochleovestibular nerve or direct inner ear involvement.

Cranial nerve deficits tend to be grouped as VII through XII and II through VI depending on the site of origin and extent of the mass, although the deficits are typically of only one or two nerves at the time of presentation—most commonly, cranial nerves V and VI. Carotid artery occlusion can lead to signs and symptoms of ischemia.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anatomy

The anatomy of interest is that of the petrous apex (Figs. 104.15–104.17) described in detail in Chapter 104 (Fig. 104.48). It is also useful to understand the relationship of cranial nerves V and VI to the petroclival fissure region and the petrous segment of the carotid canal (Fig. 112.2). Collateral knowledge about the entire temporal bone and related cranial nerves is also a general requisite for interpreting studies of patients with petrous apex masses.

Pathology and Patterns of Disease

The appearance, patterns of growth, and pathophysiology of tumor growth in general is discussed in Chapter 21; those of chondrosarcomas are discussed more specifically in Chapter 39.

The masses arise close to or within the petroclival fissure from persistent embryologic cartilage rests near the petroclival synchondrosis. They extend predominantly lateral to the petrous apex and to a lesser extent medially to involve the basisphenoid/upper clivus. When the extent is predominantly medial, the spread pattern mimics that of a chordoma, likely contributing to the long-term confusion between the two lesions.

These often compress cranial nerves III through VI, VII, and VIII when they are more superior in origin, which is the most common location, and cranial nerves IX through XII when somewhat lower in origin or extent. The tumors may become adherent to major vessels including the dural sinuses, carotid artery, and jugular vein. Involvement of these transiting structures may be associated with obvious remodeling or more frank erosion of the internal auditory canal, carotid canal, and jugular fossa. The bony labyrinth may eventually be involved.

Pathologically Altered Function

Typically, there are no deficits created early in the pathogenesis of these chronically progressive tumors. At some point, the bony eustachian tube may be compressed with resulting eustachian tube dysfunction or otitis media with effusion. Extensive lesions can cause compressive cranial neuropathies and inner ear dysfunction.

FIGURE 125.1. Two patients with osteochondral lesions of the petrous apex. A: A lesion composed mainly of mature bone along the petrous ridge. B: A lesion composed mainly of less distinct mature bone than the one in (A) at the petroclival junction.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

Specific protocols for computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) studies for investigating petrous apex masses appear in Appendixes A and B. These are typically studied with dedicated contrast-enhanced imaging of the temporal bone. Computed tomographic angiography and MR angiography are included as necessary. Diagnostic catheter angiography is typically done as a prelude to endovascular interventions or occasionally to confirm the diagnosis.

Pros and Cons

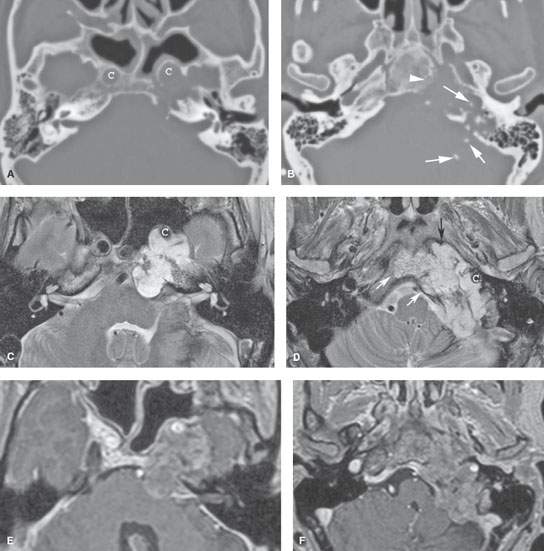

MRI provides a definitive diagnosis when typical morphologic features and growth pattern of the mass are expressed on various pulse sequences. Differentiation from all other petrous apex pathology is relatively simple based on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. MRI is typically preferred for posttreatment surveillance.

CT is excellent for bone detail that helps set the timetable of the lesion as an aid to the differential diagnosis. As well, it is useful for planning the operative approach and may be used for surveillance when nonoperative “watchful waiting” is chosen, although that is more typically done with MRI.

Controversies

There is still some debate about whether some chordomas are chondroid variants of chordoma or a true chondrosarcoma. This currently may make only a limited difference in prognosis given modern skull base surgery and proton beam therapy now available to treat these rare tumors. The debate is best left to the pathologic community.

MANIFESTATIONS OF DISEASE

Chondrosarcoma of the Petrous Apex

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

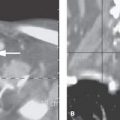

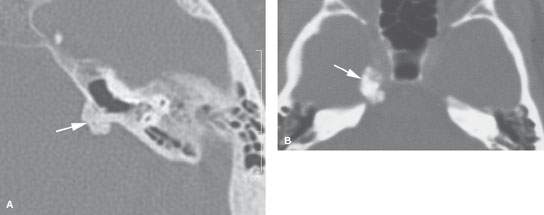

The CT appearance of chondrosarcomas is described in Chapter 39 (Figs. 39.2–39.4, 39.9, 125.2, and 125.3). That of paragangliomas in general is discussed in Chapter 33 and more specifically with regard to paragangliomas of the temporal bone in Chapter 123. Other benign tumors that primarily arise from the petrous apex are rare and usually of mesenchymal or bone origin, such as osteochondroma (Fig. 125.1) and fibromyxomas, and are discussed in Chapters 32 and 35 through 40 and indicated in the introduction to those chapters.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

From Clinical Data

The specific diagnosis of a petrous apex mass usually cannot be anticipated clinically. If there are fifth and sixth cranial nerve deficits, then a mass at the petrous apex certainly comes into the differential diagnosis. However, the responsible lesion may be cholesterolosis or mucocele in addition to benign, malignant, and vascular processes that can affect this anatomic region. Signs of infection lead to the consideration of petrous apicitis.

From Supportive Diagnostic Techniques

It is absolutely essential that these and other potentially surgical lesions of the petrous apex not be confused with normal asymmetry of the petrous apices, minor mucosal disease in apex air cells that remain partially aerated, and venous lakes or arachnoid granulations of the skull base (Figs. 104.15–104.17A and Fig. 112.6).

The combination of MRI and CT easily differentiates petrous apex cholesterolosis and mucocele from epidermoid cysts, arachnoid granulations, the few benign and malignant neoplasms, and the number of relatively uncommon inflammatory pathologies that can involve the petrous apex (Chapters 112 and 114–116). The benign tumor differential is most commonly between meningioma and nerve sheath tumor arising from the fifth and eighth cranial nerves or cranial nerves within the jugular foramen and paraganglioma (Chapters 123 and 124). These needing to be differentiated from malignant tumors including chordoma (Fig. 125.4), chondrosarcoma, a rare metastasis, and spread of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Chapter 126).

FIGURE 125.2. Chondrosarcoma of the petrous apex. A, B: Computed tomography showing a mass eroding the bone at the left petroclival junction and carotid canal (C) with internal chondroid matrix calcifications (arrows in B). The margin at the clivus is fairly sharp with a narrow zone of transition, suggesting low-grade behavior. C–F: Magnetic resonance (MR) allows for better delineation of the extent of the mass, which involves the prevertebral space (black arrow), clivus (white arrow), and posterior fossa and displaces the carotid artery (C) anteriorly. The MR images confirm sharp bony margins with narrow zones of transition. T2-weighted images show the predominantly cerebrospinal fluid–equivalent signal intensity within the mass corresponding to variably mineralized chondroid matrix (C, D). Postcontrast heterogeneous somewhat “solid”-appearing enhancement is seen (E, F).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree