PETROUS APEX MUCOSAL DISEASE INCLUDING PETROUS APICITIS

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging can make the presumptive diagnosis of petrous apex infection, especially when combined with computed tomography findings, and can identify potentially life-threatening intracranial complications.

- Computed tomography is useful in treatment planning including various surveillance strategies depending on the extent of disease and chosen therapeutic interventions.

- Radionuclide studies can help to establish the diagnosis and assess response to antimicrobial therapy.

- Incidental mucosal disease at the petrous apex is a common computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging finding that most often requires, at most, a watchful waiting management strategy.

INTRODUCTION

Etiology

Petrous apex mucosal disease is an acquired inflammatory disease that arrives at that point usually along an air cell tract leading to the petrous apex. It is essentially the same disease that occurs in the middle ear and mastoid. As such, petrous apex inflammatory disease, whether infectious or reactive, has many of the same etiologies as that of disease arising in the mastoid and middle ear. In general, this means that infectious vectors or other inflammatory challenges will produce the same range of pathology and the complications of that pathology as discussed in Chapters 110 and 111.

Infectious and inflammatory entities that may involve the petrous apex as part of more generalized skull base disorder, including necrotizing otitis externa (Chapter 114), skull base osteomyelitis (Chapter 115), and conditions such as Wegener granulomatosis (Chapter 17 and 116) and Langerhans histiocytosis (Chapters 19 and 116), are discussed in those dedicated chapters.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

This is a rare sporadic condition with no known predisposing conditions except that the petrous apex must contain air cells and at some point there would need to have been an initial inciting inflammatory insult (Figs. 112.1 and 113.1). That initial event is typically not established by the patient history. It is likely that this disease would have a range of prevalence and epidemiology similar to middle ear and mastoid inflammatory diseases discussed in Chapters 110 and 111; however, the rarity of the more severe forms of the disorder, such as suppurative petrous apicitis, prohibits meaningful insights.

Clinical Presentation

Patients typically will present with otalgia and headaches and perhaps fever and signs of meningeal irritation leading to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). Occasionally, acute inflammatory changes that extend beyond the petrous apex will produce an outright fifth or, more likely, sixth cranial nerve deficit (Figs. 110.9 and 112.2). The clinical triad of otorrhea, headache, and diplopia is known as Gradenigo syndrome.1 Petrous apex mucosal disease that is essentially inconsequential is commonly discovered on MRI studies of the brain done for often unrelated symptoms.

Pathophysiology

Anatomy

The anatomy of interest is that of the petrous apex (Figs. 104.15–104.17) and mastoid air cell tract development, as those air cells populate the petrous apex described in detail in Chapter 104 (Fig. 104.47). It is also useful to understand the relationship of cranial nerves V and VI to the petroclival fissure region and the petrous segment of the carotid canal.

Pathology and Patterns of Disease

The appearance of mucosal inflammatory disease in the air cells of the petrous apex on imaging studies is a reflection of the likely acuity and severity of the disease process resulting from the pathophysiologic mechanism of inflammation as discussed in Chapters 13 through 16.

In petrous apex mucosal disease, the obstruction of the air cell tract that is due to inflammatory mucosal disease results in resorption of air and chronic inflammation in the distal occluded cells. The mucosa may become chronically friable and enter a cycle of repeated hemorrhage, due to the friability, and continued inflammation becomes established. Cholesterol and other end-stage blood products will then accumulate in a cystic milieu; eventually, cholesterolosis may result. If there is no bleeding, a simple mucocele may form at the petrous apex. These two entities are discussed in Chapter 113.

More frequently, the air cells do not become obstructed or they remain completely obstructed, and no expansile component to the disease will exist. The inflammation may be self-limited and resolve without treatment, perhaps being related to eustachian tube dysfunction or allergy (Fig. 112.1). It might be infectious and may respond to empiric antimicrobial treatment also aimed at treating concomitant mastoid and middle ear disease that may be coincidental or the primary problem (Fig. 112.1H). Infectious petrous apex mucosal disease, in relatively rare instances, may also go on to complications similar to the range seen with acute and chronic otomastoid inflammatory diseases.

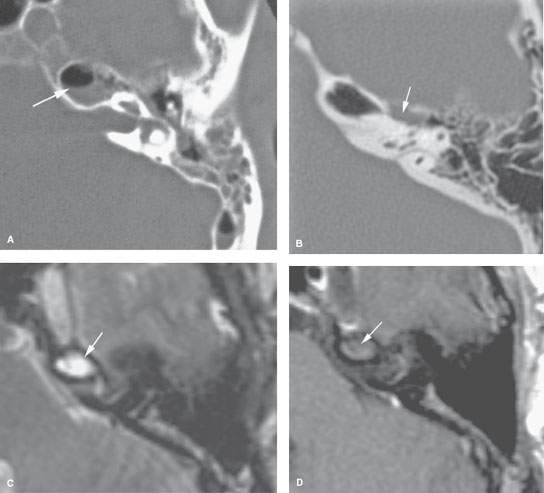

FIGURE 112.1. Imaging studies in patients demonstrating a spectrum of findings at the petrous apex that may have no consequence or require follow-up. A: Patient 1. Computed tomography (CT) with incidental findings of mucosal thickening in the middle ear, mastoid, and petrous apex (arrow). Follow-up study showed the findings to have cleared without treatment, thus having no significance. B: Patient 2. Incidental mucosal thickening isolated to the petrous apex air cells. CT shows incidental mucosal thickening along the superior labyrinthine air cell tract (arrow). These findings cleared without therapy. C, D: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of Patient 3 with incidental mucosal thickening seen in petrous apex air cells. T2-weighted (T2W) images (C) show signal intensity consistent with mucosal thickening or fluid at the petrous apex. The contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image (D) shows no abnormal enhancement. These findings subsequently cleared without therapy. E–G: Patient 4 with left petrous apex mucosal thickening that was identified as an incidental finding. The contrast-enhanced T1W image (E) shows the mucosal thickening in the petrous apex air cells associated with enhancement confined to the mucosa within the air cell (arrow. The T2W image (F) shows fairly typical signal intensity of mucosal thickening and/or fluid. (G) Because of the enhancement, a baseline CT was obtained. This shows septae within the petrous apex air cell to be intact (arrow) and a small amount of thickening of mucosa in some other mastoid air cells. These findings cleared without treatment. This likely was a very low-grade inflammatory process, the equivalent of mastoiditis, that only involved the petrous apex air cells. Incidental mastoid inflammation is a very frequent finding on both CT and MRI studies. H: Patient 5 with an incidental discovery of fairly extensive opacification of both petrous apex and mastoid air cells. The disease showed no aggressive behavior. This patient was followed for several years with no change in these findings. The patient had no symptoms related to the findings. I, J: Patient 6 had prior canal wall-down mastoid surgery and persistent headaches. CT shows mucosal thickening within the petrous apex. The surgeon believed this to be responsible for the headaches. In (J), a radionuclide study reveals no significance at the petrous apex. Despite this, the patient was explored. Noninflammatory mucosal changes were found at the right petrous apex. The patient’s symptoms did not resolve following surgery.

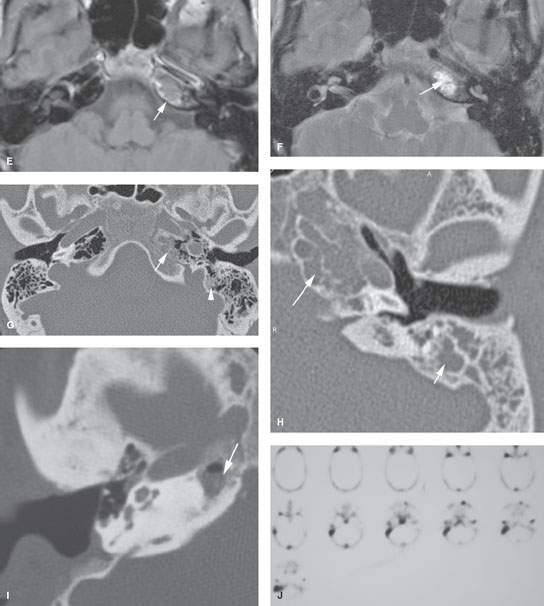

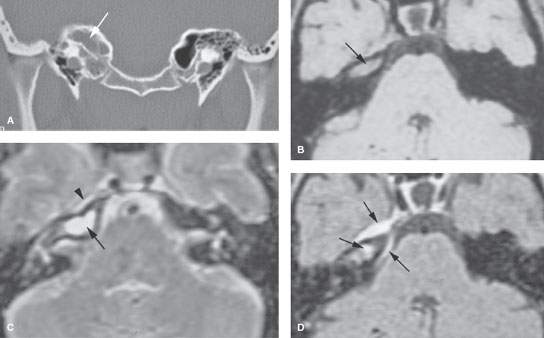

The petrous apex mucosal changes disease may be limited to simple mucosal thickening with or without active inflammation (Fig. 112.1A–D). Such inflammation might be manifest by contrast enhancement more easily appreciated on MRI than CT (Fig. 112.1E). This mucosal change can be more exuberant and when due to bacterial or fungal infections may cause localized bone erosion such as that seen in coalescent mastoiditis (Chapter 110); the process then is properly referred to as acute or subacute petrous apicitis and early osteomyelitis with all of the potential problems of a fairly serious disease process with life-threatening dimensions if left untreated (Figs. 112.2 and 112.3). Such infectious petrous apicitis might progress to induce a nasopharyngeal abscess or dural phlegmon and then epidural or subdural empyema (Fig. 112.3). The disease may propagate along veins to the dural sinuses and lead to substantial complications involving the brain and subarachnoid space.

Cranial involvement is thought to result from direct spread of inflammation at the petrous apex. However, cranial nerve VI paresis can be found in association with mucosal disease anywhere in the temporal bone, such as that resulting from otitic hydrocephalus; this is thought to be the result of reduced venous outflow, typically in association with large sinus thrombophlebitis.

FIGURE 112.2. A patient with severe headaches, fever, facial pain in the distribution of the right trigeminal nerve, and a sixth cranial nerve palsy. A: Computed tomography study showing opacification of petrous apex air cells without gross destructive changes. B: Non–contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image showing abnormal signal in petrous apex air cells (arrow). C: T2-weighted image showing fluid and/or mucosal thickening in the petrous apex air cells (arrow) and a possible small epidural fluid collection (arrowhead). D: Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image showing enhancement of the contents of the petrous apex as well as a marked amount of surrounding dural enhancement (arrows) extending to the junction of the clivus and petrous apex. This is due to pyogenic petrous apicitis with secondary dural phlegmon and possibly early epidural abscess.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree