Abstract

Autosomal recessive pontocerebellar hypoplasia comprises a group of devastating neurodegenerative disorders that lead to severe motor and cognitive impairment. Life expectancy varies based on subtype and is unpredictable; few patients live into adulthood. Prenatal diagnosis is challenging, as midtrimester imaging is usually normal. Families with a known mutation should be offered genetic counseling to discuss deoxyribonucleic acid banking of affected individuals, preimplantation, and prenatal testing options.

Key Words

progressive neurodegenerative disorder, microcephaly, seizures, motor and cognitive delay

Introduction

Autosomal recessive pontocerebellar hypoplasias (PCHs) are a group of severe neurodegenerative disorders affecting the cerebellum and pons. This disease appears in fetal or neonatal life with subsequent pontocerebellar degeneration, progressive microcephaly, and atrophy of the cerebral cortex. Most affected individuals have profound motor and cognitive deficits. Life expectancy generally lasts into infancy or childhood, though there are reports of some individuals with PCH who live into adulthood. At the time of this publication, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man cites 10 known PCH subtypes (PCH1-10).

Disorder

Definition

Individuals affected by PCH are typically diagnosed in the neonatal period because of profound motor and cognitive delay. The phenotype and life expectancy vary based on PCH subtype. However, most individuals with PCH share common clinical manifestations including profound motor and cognitive delay, movement disorders, epilepsy, hypotonia, feeding difficulties requiring gastrostomy, and respiratory distress.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Autosomal recessive PCH is rare and the prevalence is unknown. Several genetically isolated communities with founder mutations are reported in the literature. One such founders’ community in the Netherlands has a carrier frequency of PCH2 of 14.3%.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

PCH is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. Several gene mutations have been isolated among individuals affected by PCH including TSEN54 , RARS2 , EXOSC3 , and PCLO . PCH2 is the most common PCH subtype and is caused by a mutation in TSEN54 ; other TSEN- related PCH disorders include PCH4 and 5. Of note, TSEN54 , TSEN2 , and TSEN34 encode the transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA) splicing endonuclease complex subunits whereas RARS2 mutation, which is implicated in PCH6, encodes mitochondrial arginyl tRNA synthetase. However, it is unclear why the cerebellum and pons are most severely affected, unlike other structures that also rely heavily on protein synthesis.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Severe motor delay in an infant with abnormal neuroradiologic imaging increases the suspicion for PCH. The clinical presentation depends on the subtype of PCH, but most forms share several common clinical manifestations including the following:

- •

seizures

- •

suck-and-swallow impairment, which can result in breastfeeding challenges and often require gastrostomy placement

- •

profound motor and cognitive delay

- •

loss of developmental milestones if they were once achieved

- •

progressive microcephaly

- •

hypotonia

- •

chorea

- •

irritability

- •

visual impairment

- •

increased risk of malignant hyperthermia associated with febrile illness but not with general anesthesia

- •

elevated creatinine kinase

- •

arthrogryposis

- •

respiratory distress and/or obstructive sleep apnea

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound.

Prenatal ultrasound (US) of affected fetuses is usually normal. Posterior fossa structures appear normal at midgestation as cerebellar development lags typically in third trimester. In the third trimester, nomograms for posterior fossa structures could be used in pregnancies for families with an affected child. However, even among families with a known affected child, detailed prenatal sonographic surveillance may fail to diagnose PCH.

There are certain findings among families with an affected child that raise suspicion: polyhydramnios or arthrogryposis may be visualized in 1%–2% of cases with PCH. Microcephaly may be detected between 32 and 35 weeks. For some affected fetuses with PCH5, chorea and/or seizures first manifest in utero and may be perceived by the mother and visualized on US. In addition, hydrops may be associated with PCH. However, thus far, the role of US in prenatal diagnosis is limited.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

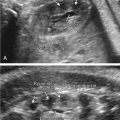

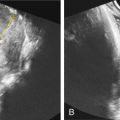

Fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the third trimester may demonstrate lagging cerebellar growth. Fig. 142.1 demonstrates MRI findings in affected neonates from 2 weeks to 9 months of life. In addition, MRI tractography may show absence of pontine crossing fibers in affected fetuses ( Fig. 142.2 ). Rarely, cerebellar cysts may be visualized.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree