Posterior Compartment: Malignant Masses

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography provide the critical and usually definitive data needed in the diagnosis and management of malignant posterior compartment masses.

- Prompt and accurate imaging can help to avoid rare and potentially severe complications related to the cervical spinal cord in some posterior compartment pathology.

- Imaging-guided tissue sampling may be useful in the management of these masses.

INTRODUCTION

The posterior compartment of the neck is discussed in this chapter as the site of origin of malignant mass lesions of the infrahyoid neck. Benign posterior compartment masses were discussed in Chapter 160. The posterior compartment is a relatively uncommon site of origin of neck masses. It can be a secondary site of lymphoma and metastatic disease. This compartment is not often secondarily involved, even by malignant masses that originate in the visceral compartment, retropharyngeal space, and lateral compartment, but they may mimic the presentation of lateral compartment disease as discussed in Chapter 150. The spectrum of diseases that might present as a mass in the posterior compartment is outlined in Table 162.1.

Clinical Presentation

The primary presentation is usually that of a neck mass of uncertain etiology without associated signs or symptoms or other physical findings. There is often a history of progressive enlargement of the mass. Malignant tumors are more likely to be painful than benign tumors.

Tenderness and fever and associated generalized swelling may be present and are much more likely in the inflammatory conditions discussed in Chapter 160. Vascular malformations may be compressible and/or pulsatile, and masses may feel obviously cystic to palpation; these are not typical features of a malignant tumor.

Neurologic dysfunction is usually due to cervical nerve root involvement but may be due to involvement of the contained phrenic nerve and nearby cervical sympathetics, vagus nerve, and spinal cord. Signs of cervical spinal cord compromise, when present, may suggest that a very urgent problem is at hand.

APPLIED ANATOMY

The anatomy of the posterior compartment that directs the spread of masses in the prevertebral and paravertebral spaces is simple. The prevertebral fascia is thick and relatively resistant to the spread of even most malignant pathologic processes compared to the fascia of the visceral and lateral compartments. This deep layer of fascia then reflects laterally over the vertebral transverse processes and the attachments of the scalene muscles to cover the paravertebral portion of the posterior compartment of the neck, as discussed in Chapters 142 and 149 (Figs. 142.3A, 149.1, and 149.2). It is penetrated laterally by small vessels and the cervical nerve rootlets, with the most prominent of the latter being those of the brachial plexus. These fascial attachments provide a relatively resistant barrier to the spread of masses between the posterior and other compartments, although masses that follow traversing nerves and vessels can relatively easily track from one compartment to another (Fig. 162.1).

Structures of Interest

The analysis of a malignant mass of the posterior compartment (prevertebral and paravertebral spaces) depends on a thorough understanding of its relationship to the following structures:

Superiorly: Hyoid bone as the arbitrary boundary

Superiorly: Hyoid bone as the arbitrary boundary

Inferiorly: Thoracic inlet, supraclavicular fossa, and posterior chest wall

Inferiorly: Thoracic inlet, supraclavicular fossa, and posterior chest wall

Anteriorly: Retropharyngeal space and lateral compartments

Anteriorly: Retropharyngeal space and lateral compartments

Posteriorly: Cervical spine and pre- and paravertebral muscles and fascia and more superiorly the lower clivus if in the prevertebral space; if of paravertebral space origin, the containing prevertebral fascia and subcutaneous soft tissues

Posteriorly: Cervical spine and pre- and paravertebral muscles and fascia and more superiorly the lower clivus if in the prevertebral space; if of paravertebral space origin, the containing prevertebral fascia and subcutaneous soft tissues

Medially: Not applicable in the prevertebral space; spinal and neurologic elements if in the paravertebral space

Medially: Not applicable in the prevertebral space; spinal and neurologic elements if in the paravertebral space

Laterally: Lateral compartment (mainly the posterior triangle) of the neck/carotid sheath/brachial plexus from the trunks distally

Laterally: Lateral compartment (mainly the posterior triangle) of the neck/carotid sheath/brachial plexus from the trunks distally

IMAGING APPROACH

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The infrahyoid neck is mainly evaluated with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The specifics and relative value of using these studies in this anatomic region are reviewed in Chapter 149. Problem-driven protocols for CT and MRI are presented in Appendixes A and B. In general, MRI is more definitive than CT for the evaluation of posterior compartment masses, both for lesion characterization and its relationship to the spinal nerve roots and cord. MRI should be done urgently or emergently if there is any hint that the cervical spinal cord might be threatened.

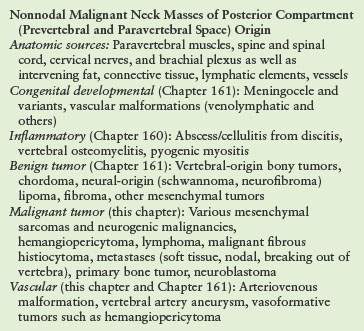

TABLE 162.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS BY GENERAL ETIOLOGIES OF MALIGNANT POSTERIOR COMPARTMENT NECK MASSES

Other

Ultrasound has a potential triage role to play in the evaluation of a pulsatile mass but is most often cost additive and unlikely to contribute to definitive medical decision making. It may actually delay a more timely use of a likely more definitive CT or magnetic resonance (MR) study.

Catheter angiography is used selectively and most often as a prelude to endovascular intervention once the diagnosis has been established by imaging and related computed tomographic angiography or MR angiography.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND PATTERNS OF DISEASE AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AS SEEN ON MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING AND COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

The initial evaluation of a potential mass in the posterior compartment is highly driven by the patient age, specific clinical situation, and related likely disease category; therefore, these factors are a fundamental consideration used as part of the framework for the diagnostic process and related medical decision making. It first must determine whether the posterior compartment is the site of origin and then whether the mass has secondarily involved the lateral or visceral compartment and related retropharyngeal space as a transspatial process. Transspatial malignant masses that begin in the posterior compartment are rare (Fig. 162.1). The mechanisms and potential routes of transspatial spread in these aggressive pathologies, such as lymphoma, metastases, and sarcomas, are by direct invasion and/or are perineural along the cervical nerve roots, potentially leading to the epidural space and cervical spinal cord (Figs. 162.2 and 162.3).

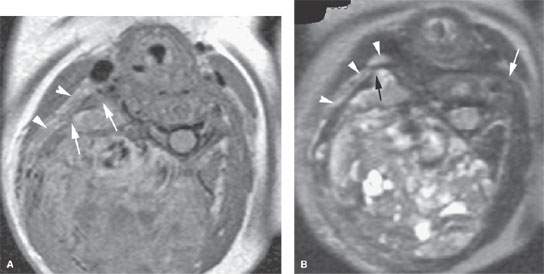

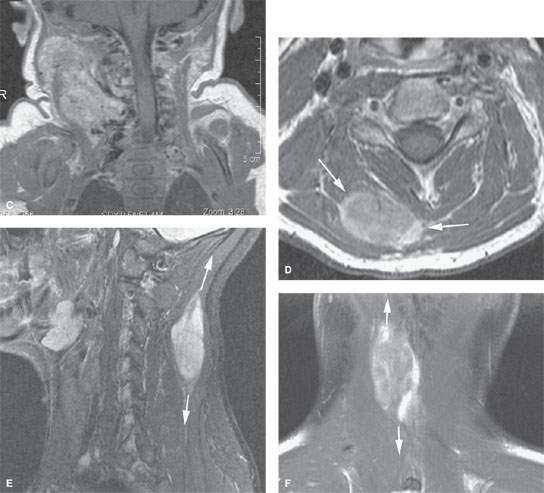

FIGURE 162.1. Two patients with malignant tumors of the neck posterior compartment. A–C: Postcontrast T1-weighted (T1W) magnetic resonance (MR) (A) and T2-weighted MR (B) in Patient 1, a young child presenting with a firm posterior neck mass growing through the natural areas of dehiscence in the prevertebral fascia (arrows) to involve the posterior triangle of the lateral compartment (arrowheads). In (C), there is growth of this tumor from below the skull base to the supraclavicular fossa and upper posterior chest wall. Biopsy revealed a hemangiopericytoma. (NOTE: The large flow voids seen in [C] are a morphologic feature that is helpful for the differential diagnosis and to choose a less risky imaging-guided biopsy site.) D–F: Patient 2. Contrast-enhanced T1W MR of an adult with a synovial cell sarcoma. The solid mass with aggressive margins is shown to be confined within the posterior compartment muscles (arrow in D), and the tendency for this growth to be directed within these muscle bundles toward the skull base and supraclavicular fossa–upper posterior chest wall is demonstrated in the sagittal (arrow in E) and coronal planes (C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree