Posterior Compartment: Prevertebral and Paravertebral Space Inflammatory Conditions

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography provide the critical and usually definitive data needed in the diagnosis and management of posterior compartment prevertebral and paravertebral space inflammatory and infectious diseases.

- Prompt and accurate imaging can help to avoid potentially severe neurologic compromise in prevertebral space infections.

- Myelography should be done reluctantly and with the greatest care if found to be necessary.

- Imaging-guided aspiration and/or tissue sampling may be used to assist in the management of these infections.

INTRODUCTION

Infections of the prevertebral space discussed in this chapter and those of the retropharyngeal space (RS) discussed in Chapter 151 can result in significant morbidity and mortality. To some extent, they should be considered together since their imaging picture may overlap; however, the conditions tend to diverge in some instances based on their clinical presentation. Timely diagnosis and proper treatment are critical in preventing sequelae such as airway obstruction, epidural abscess and cervical cord injury, mediastinitis, carotid artery aneurysm, and cavernous sinus thrombosis.

The prevertebral space is discussed in this chapter as the site of origin of infections and other inflammatory diseases of the head and neck. The prevertebral space is mainly involved by inflammatory pathology of the spine, usually discitis and/or vertebral osteomyelitis, or facet infection (Fig. 160.1). Other posterior compartment inflammatory diseases are rare in the absence of penetrating trauma or an open surgical procedure. Differentiating prevertebral space infections from musculoskeletal chronic inflammatory conditions is an important part of this process (Fig. 160.2). Infectious disease originating from the cervical spine must be differentiated early in the diagnostic process from that originating due to pharyngeal disease to avoid a potentially catastrophic neurologic event involving the cervical spinal cord.

Clinical Presentation

A prevertebral space–origin infection will present with neck pain that might be mechanical and perhaps an occipital headache. The combination of fever, neck pain, and limitation of cervical spine range of motion frequently raises the clinical suspicion of meningitis. Such a presentation and/or any neurologic deficit that might be due to cervical cord involvement should elevate the imaging evaluation to a very urgent or emergent status.

Infections of the prevertebral space may mimic those of the RS, causing dysphagia or odynophagia as a presenting complaint in adults; in infants, such swallowing problems may manifest simply as “feeding difficulties.” Airway compromise is possible. Otalgia is possible.

Fever is very common in infection, and the white count should be elevated. Lack of these circumstances suggests, but does not indicate for certain, a noninfectious inflammatory etiology. This is especially true in the immune-compromised population.

APPLIED ANATOMY

The anatomy of the posterior compartment that directs the spread of inflammatory disease in the prevertebral and paravertebral spaces is simple. The prevertebral fascia is thick and relatively resistant to the spread of pathologic processes compared to the fascia of the visceral compartment. This provides a relatively resistant barrier to spread of pus between the prevertebral space and RS, although reactive edema spreads readily from one space to another (Fig. 160.1). A musculofascial sheath associated with the prevertebral longus colli muscles lies posterior to the prevertebral fascia. This deep layer of fascia then reflects laterally over the vertebral transverse processes and the attachments of the scalene muscles to cover the paravertebral portion of the posterior compartment of the neck, as discussed in Chapters 142 and 149 (Figs. 142.3A, 149.1, and 149.2). It is penetrated laterally by small vessels and the cervical nerve rootlets, with the most prominent of the latter being those of the brachial plexus.

The RS lies between the visceral compartment and the prevertebral fascia in free communication with the lateral compartment of the neck and the carotid sheath.

Structures of Interest

The analysis of an inflammatory process or mass of the posterior compartment (prevertebral and paravertebral spaces) depends on a thorough understanding of its relationship to the following structures:

Superiorly: Hyoid bone as the arbitrary boundary

Superiorly: Hyoid bone as the arbitrary boundary

Inferiorly: Thoracic inlet, supraclavicular fossa, and posterior chest wall

Inferiorly: Thoracic inlet, supraclavicular fossa, and posterior chest wall

Anteriorly: RS and lateral compartments

Anteriorly: RS and lateral compartments

Posteriorly: Cervical spine and pre- and paravertebral muscles and fascia and more superiorly the lower clivus if in the prevertebral space; if in the paravertebral space, the posterior boundary is the containing fascia and subcutaneous soft tissues

Posteriorly: Cervical spine and pre- and paravertebral muscles and fascia and more superiorly the lower clivus if in the prevertebral space; if in the paravertebral space, the posterior boundary is the containing fascia and subcutaneous soft tissues

Medially: Not applicable in prevertebral space; spinal and neurologic elements if in the paravertebral space

Medially: Not applicable in prevertebral space; spinal and neurologic elements if in the paravertebral space

Laterally: Lateral compartment (mainly the posterior triangle) of the neck/carotid sheath/brachial plexus from the trunks distally

Laterally: Lateral compartment (mainly the posterior triangle) of the neck/carotid sheath/brachial plexus from the trunks distally

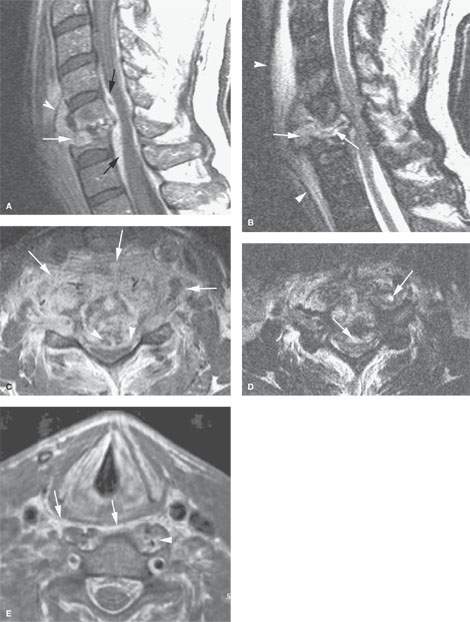

FIGURE 160.1. Three patients with discitis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) studies were done. A–D: Patient 1 had very advanced discitis. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image in (A) shows the inflammatory tissue within the disc space (white arrow) and extending into the prevertebral space, displacing the anterior longitudinal ligament (white arrowhead). The epidural abscess and phlegmon is shown by the black arrows. In (B), T2-weighted (T2W) MRI shows the extensive edema within the prevertebral space displacing the prevertebral soft tissues and related fascia (white arrowheads). The infected material within the disc space is of variable signal intensity (white arrows) and extends into the prevertebral space as well as the epidural space, impressing the spinal cord posteriorly (white arrows). In (C), a contrast-enhanced T1W image in the axial plane shows the very extensive phlegmon involving the vertebral body, prevertebral space, paravertebral space, and retropharyngeal space (RS) (arrows) as well as the epidural abscess (arrowheads). In (D), a T2W image shows grossly necrotic fluid areas within both the epidural abscess and the phlegmon, extending into the spaces anterior to the spine (arrows). E–G: Patient 2 with early discitis presenting with fever and neck pain. In (E), the contrast-enhanced T1W image shows abnormal enhancement within the RS displacing the pharyngeal musculature (arrows). There is also abnormal enhancement of the prevertebral muscles within the prevertebral space; those on the left also appear swollen (arrowhead). In (F), the T1W sagittal image shows the very extensive enhancing tissue within the prevertebral and retropharyngeal spaces (arrows) displacing the pharyngeal musculature (arrowheads). Also note the prominence of the epidural vascular plexus within the spinal canal. It was difficult on this image to demonstrate any definite evidence of enhancement of the intervertebral disc. In (G), the T2W sagittal image shows the extensive edema and phlegmon displacing the pharyngeal musculature (arrowheads). The source of infection is shown to be the disc with abnormally bright signal intensity (arrowheads). Discitis was confirmed. H, I: Contrast-enhanced CT study in Patient 3, who presented with lateral neck swelling and pain. Edema can be seen both in the posterior triangle and in the posterior compartment of the neck. The imaging revealed that there was actually prevertebral and paravertebral soft tissue swelling and an epidural abscess (arrows) responsible for the patient’s complaints.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree