PRIMARY BONY AND METABOLIC DISORDERS OF THE CRANIOFACIAL SKELETON

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography is the primary tool for the evaluation of craniofacial skeleton osteodystrophies, metabolic disease, and reactive changes such as marrow hyperplasia.

- Magnetic resonance imaging may be used occasionally for problem solving.

- Magnetic resonance imaging findings may go unnoticed or be confusing in these disease states.

- Imaging sometimes does not specifically explain a functional deficit caused by these conditions.

The conditions that primarily affect bones throughout the body may occasionally express themselves in isolated form in the craniofacial skeleton. More commonly, the craniofacial expression of such disorders is part of a bony condition that involves more than one segment of the skull base and/or facial bones including the temporal bones (Chapter 119). The craniofacial bone involvement may also be part of a systemic process, which may be generally categorized as developmental/dysplastic, metabolic, dystrophic, or reactive.

Patients may present with a variety of complaints, physical findings, and functional deficits that are common in other pathologic conditions of the craniofacial skeleton. The causative conditions are discussed in summary form here with regard to their specific craniofacial manifestations. These conditions are discussed in general with regard to their pathophysiology, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance appearance, and treatment in Chapter 43.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

In general, these skeletal disorders are best evaluated with standard, noncontrast high-resolution facial bone imaging. Specific protocols by indication appear in Appendix A. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used adjunctively in very limited circumstances, such as when there is doubt about the diagnosis and there could be an infiltrating processes with dural or other intracranial extension. Occasionally, complicating mucocele or infection might be evaluated with MRI for reasons discussed in Chapter 84.

Pros and Cons

The pattern of disease and proper diagnosis generally will be much more apparent on CT. In fact, when diffuse, bilateral, and reasonably symmetric changes are present, even relatively advanced disease can go unnoticed on MRI. Also, more localized disease such as fibrous dysplasia (Chapter 91) can present very confusing findings, sometimes mimicking a more threatening mass on MRI, while the nature of the disease becomes quite obvious on CT. MRI really needs to be limited to problem solving in these types of disorders as suggested previously.

RENAL OSTEODYSTROPHY

Facial skeletal changes in renal osteodystrophy include osteitis fibrosa cystica, a fibrous dysplasia–like form, and a rare form known as uremic leontiasis ossea. The pathophysiology leading to the craniofacial expression and imaging appearance of these various forms of renal osteodystrophy is summarized in Chapter 43 (Figs. 43.1, 43.2, and 93.1).

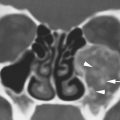

Osteitis fibrosa cystica is an active-phase finding with peritrabecular fibrosis and cystic brown tumors (Fig. 43.1A–D). There is gross thinning multiple bones cortices, coarsened trabeculae, osteolytic lesions, and mixed osteolytic and sclerotic bone that produce the radiographic “salt-and-pepper” appearance of the skull1,2 (Figs. 43.1 and 93.1). The fibrous dysplasia–like form is diffuse and generalized rather than localized like fibrous dysplasia and is further distinguished by indistinct corticomedullary interfaces. Uremic leontiasis ossea is rare and characterized by significant hypertrophy of the jaws with serpiginous channels within the bone and indistinct cortical margins.2

Rarely, a single or multiple brown tumors in the head and neck region, associated with either primary or secondary hyperthyroidism, will be a presenting clinical manifestation of renal osteodystrophy (Fig. 43.1). Multiple brown tumors can present as “cherubism.” The morphology and related imaging appearance of Brown tumors is discussed in Chapter 43.

SICKLE CELL DISEASE AND THALASSEMIA

The pathophysiology leading to the craniofacial expression and imaging appearance of sickle cell disease, thalassemia, and other chronic anemia is summarized in Chapter 43.

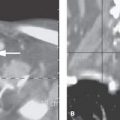

Reactive marrow hyperplasia in these anemias causes the marrow-containing bone to have a marginally “expanded” appearance due to the reactive bony changes that accompany the increased marrow space volume (Figs. 43.3, 43.4, and 93.2). This reduces the aerated volume of the adjacent paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity and can lead to symptoms of sinonasal congestion. If the clinical circumstances are not known, this pattern of reactive marrow changes can mimic an infiltrating malignant tumor. Similar changes can occur in the “driven marrow” of polycythemia vera (Fig. 93.2B–D). More often, the pattern will bring to mind a possible systemic disorder such as renal osteodystrophy or even a mild form of osteopetrosis.

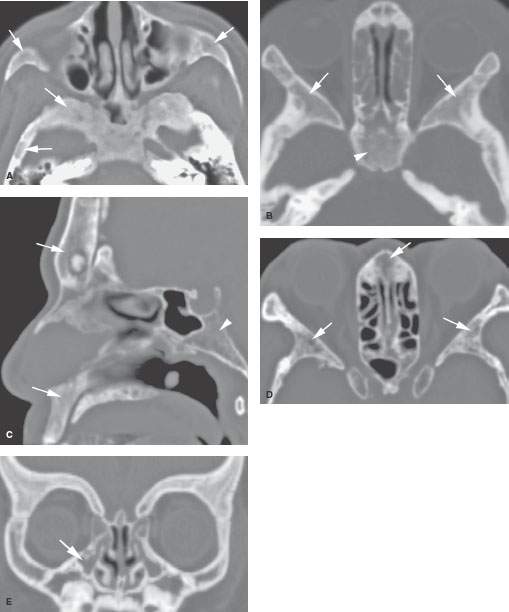

FIGURE 93.1. Four patients with various stages of renal osteodystrophy. A: A child with secondary hyperparathyroidism and related changes affecting the facial bones, central skull base, and calvarium as shown by arrows. B: A patient with renal osteodystrophy showing typical changes of that disease more obvious within the greater wing of the sphenoid (arrows) than in the upper sphenoid bone (arrowhead). C, D: An adult with renal osteodystrophy with involvement of the facial bones (arrows in C) and clivus (arrowhead in C). Bilateral and relatively symmetric involvement of the skull base and facial bones is shown by arrows in (D). E: A child with renal osteodystrophy showing how this disease can interfere with normal sinus development (arrow).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree