Chapter 8 Prosthetic Heart Valves

Introduction

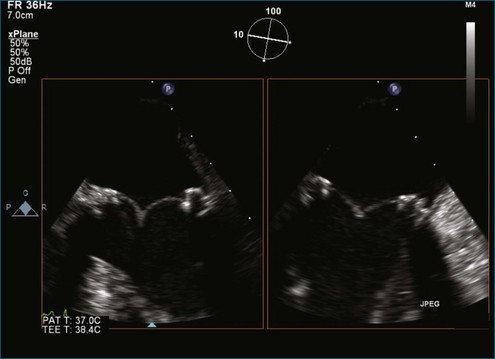

Although echocardiography is the imaging modality of choice for cardiac heart valves, it still has significant limitations when imaging prosthetic cardiac valves. These limitations are significant with bioprosthetic valves and are particularly problematic with mechanical valves. The classic limitation is the inability to evaluate mitral regurgitation (MR) from the apical window in patients with mechanical prosthetic valves because of reverberation artifacts and acoustic shadowing. Many of these limitations, particularly while imaging the mitral valve (MV), are overcome by transesophageal imaging; direct imaging from the left atrial side of the valve eliminates these shadowing artifacts, which reside on the ventricular aspect of the valve (Figure 8-1; Video 8-1). Sparse data exist regarding the use of real-time three-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (RT3DTTE) with prosthetic valves, although in a small series of four patients with endocarditis, vegetations and/or dehiscence not recognized by two-dimensional (2D) TTE were seen.1 Evaluation of prosthetic valves by RT3D transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has been extensively reviewed.2,3 In one study, RT3DTEE has been shown to be particularly accurate for diagnosing all types of prosthetic valve pathology compared with direct surgical inspection.4 However, MV visualization, particularly valve leaflet visualization, was far superior to that of aortic or tricuspid valves. Also in this study, most of the valves were free of disease and, in fact, had recently been placed. Despite being a study of 87 patients, fewer than 40 had prosthetic valves, and the number who had metallic prosthetic valves is not clear from the report.

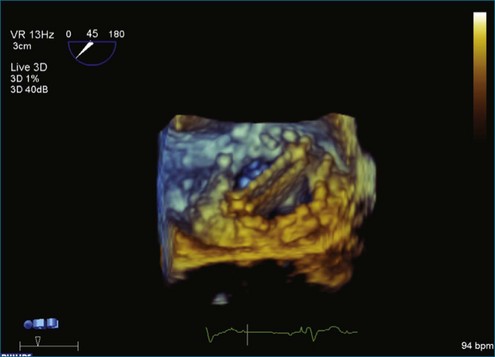

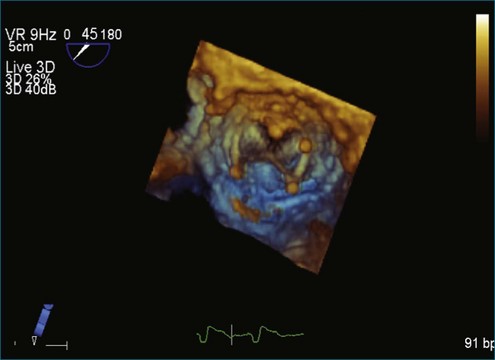

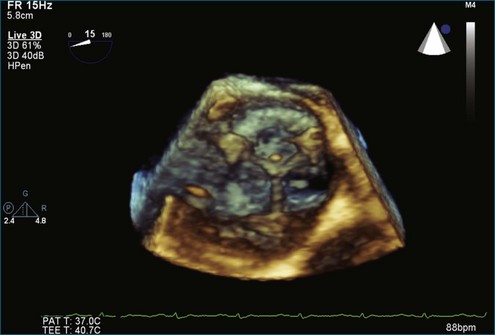

A notable advantage of RT3DTEE compared with 2DTEE for all mechanical valves in the mitral position is the ability to visualize the entire valve in one full-volume or 3D zoom capture compared with visualization of only a single thin slice by 2D (Figures 8-1 to 8-6; Videos 8-1 to 8-6). Besides live 3D imaging, RT3DTEE has the ability to acquire a 3D volume that can then be cropped and rotated to reveal pathology such as leaflet immobility, thrombi or vegetations, dehiscence, or, with the addition of 3D color, even small perivalvular leaks (see Figure 8-4 and Video 8-4). Details of the valve, such as the sewing ring, the individual stitches, the struts, and the entire leaflet motion are well visualized by RT3DTEE (see Figure 8-6 and Video 8-6). Again, such visualization is much less frequently seen in valves in either the aortic or tricuspid position.

Figure 8-3 Two-dimensional echocardiographic image of a stented bioprosthetic valve in the mitral position.

Abnormal Pathology with Mechanical Valves

Visualization of masses or the pannus on mechanical valves by RT3DTEE has not been rigorously studied because such problems are relatively uncommon. Only case reports exist of pannus formation on bileaflet mechanical valves in the mitral position evaluated by RT3DTEE, but in one published case, the pannus was identified by RT3DTEE and not seen at all by 2DTEE.5 Thrombus formation can be more precisely evaluated by RT3DTEE than by 2DTEE; in fact, this has confirmed our observation of the ability of RT3DTEE to appreciate that thrombi are larger and more numerous than thrombi detected by 2DTEE.6,7

Periprosthetic Regurgitation

RT3DTEE is invaluable for guidance of procedures to close periprosthetic regurgitation with Amplatzer (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN) vascular plugs, particularly involving the MV. This intervention and others are covered in another chapter. However, diagnosis and characterization of periprosthetic regurgitation have been evaluated somewhat systematically, and RT3DTEE has been shown to be significantly superior to 2DTEE for the determination of extent and location of periprosthetic regurgitation. In one series of 13 patients, only 2 had aortic prostheses, making statements regarding the use of RT3DTEE for aortic prosthetic regurgitation somewhat anecdotal.8 Nevertheless, in 1 of the 2 cases, no defect was found on 2DTEE, and a substantial area of regurgitation was seen with the use of RT3DTEE.

Mitral Prosthetic Dehiscence

RT3DTEE provides additional information in patients with a postoperative MV dehiscence and therefore may help plan an optimal corrective intervention. Kronzon and colleagues,9 in a series of 18 patients with dehisced MVs, 10 after replacement and 8 after repair, used RT3DTEE for echocardiographic evaluation. In all cases, the position of the valve dehiscence was more extensively characterized by RT3DTEE than with 2DTEE, and the position of dehiscence was confirmed to be correct in 10 of the patients by surgical findings. The presence of valve dehiscence was correctly diagnosed by 2DTEE in 17 of the 18 patients, but the type of valve ring or the position of the valve dehiscence could not be characterized in any case. Ten of the patients had posterior dehiscence, and four had lateral dehiscence. These positions were believed to be the most prominent because (1) the posterior annulus is the most difficult portion of the valve ring to reach surgically and (2) surgeons attempt to avoid the circumflex coronary artery.9

Guidance of Percutaneous Valve Placement

TEE is the standard for guiding percutaneous transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Data regarding the use of RT3DTEE for this particular procedure are limited, although it is routinely performed.10 Several potential advantages exist for RT3DTEE in this setting. The third dimension allows (1) more accurate assessment of the aortic annulus, the left ventricular outflow tract, and the aortic root size and shape; (2) measurement of the distance between the annulus and the left main coronary artery ostium; and 3) seating of the percutaneous valve while viewing the aortic valve en face and visualizing the valve leaflets and the tissue surrounding the prosthetic annulus.11 This en face view is critically important for placement of the prosthetic valve to avoid postprocedure perivavluar regurgitation. RT3DTEE and biplane imaging also assist with the perioperative monitoring of all procedural aspects, including advancements of guidewires into the aortic valve and the placement of pigtail catheters in the sinus of Valsalva and the left ventricle, as well as balloon valvuloplasty or valve deployment. Ultimately, 2DTEE and RT3DTEE should be used as complementary imaging modalities to assess the satisfactory positioning and function of the implanted valve.

Reports of small series of transcatheter mitral valve-in-valve implantations have appeared in the literature. RT3DTEE has also been routinely used for this purpose.12 Although this procedure is currently not available in the United States, RT3DTEE will be a mainstay for deployment of mitral valve-in-valve devices when they do become available.

Guidance of Percutaneous Valve Repair

3D echocardiography has been used for guidance during percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty and has been shown to be a suitable technique for monitoring its efficacy and complications.13 RT3DTEE may become the gold standard in describing the morphology of commissures as a good predictor of outcome after percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty.14 Balloon valvuloplasty in patients with rheumatic MV stenosis was the first percutaneous procedure used in the management of patients with MV disease. RT3DTEE not only guides the transseptal approach, it also improves the spatial orientation of the catheter system in reference to the MV and permits immediate inspection of the MV after the valvuloplasty.15

Percutaneous approaches to the management of MR continue to be developed. A large number of percutaneous devices to manage mitral dysfunction have been directed at reduction of the annulus (e.g., Viacor [Viacor, Inc., Wilmington, MA], Monarch coronary sinus retracting stent [Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA]), stabilization of the valve leaflet motion (e.g., MitraClip, Evalve [Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, IL]), or reduction of leaflet restriction (Coapys [Myocor, Maple Grove, MN], subvalvular stabilization, cutting secondary chords). Recent evidence supports the utility of the simple edge-to-edge technique (MitraClip) in those not amenable to conventional surgical repairs. Based on the initial performance of edge-to-edge repair by catheter-based technology, percutaneous edge-to-edge repair was performed in the randomized, phase II Pivotal Study of a Percutaneous Mitral Valve Repair System (EVEREST II). The results of that trial suggest that percutaneous repair with the MitraClip system can be accomplished with low rates of morbidity and mortality and with acute MR reduction to less than 2+ in the majority of selected patients. This technology may soon become a less invasive alternative to surgical mitral valve repair in the future.16,17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree