Author

Pat. #

Therapy

Response (PR, CR, SD)

Survival

Comment

(D’Avola et al. 2009)

35

35 RE (resin)

16 m

8 m

Comparison to not-in-study- included control group

(Woodall et al. 2009)

52

20 RE

(glass; no VT)

15 RE

(glass; VT)

17 no RE, BSC

13.9 m

2.7 m

5.2 m

(Hilgard et al. 2010)

108

159 RE (glass)

93 %

16.4 m

European survey

TTP 10 m

(Strigari et al. 2010)

73

RE (resin)

55 % (RECIST)

74 % (EASL)

Not reported

(Salem et al. 2010)

291

526 RE (glass)

42 % (WHO)

57 % (EASL)

17.2 m

(C-P A)

7.7 m

(C-P B)

Longitudinal cohort study. Survival in patients with PVT 5.6 m

(Sangro et al. 2011)

325

RE (resin)

Not reported

24.4 m (BCLC A)

16.9 m (BCLC B)

10.0 m (BCLC C)

European Network on Radioembolization with Yttrium-90 Resin Microspheres (ENRY): 1.-line treatment or progression after Rx or other treatment

(Carr et al. 2010)

691

99

TACE (with particles)

RE (glass)

89 %

77 %

8.5 m

11.5 m

Considering selection bias no difference

(Salem et al. 2011)

122

123

TACE

RE (glass)

49 %

36 %

17.4 m

20.5 m

TTP 8.4 vs. 13.3 m; no difference but less toxicities in RE

(Kooby et al. 2010)

44

27

TACE

RE

64 %

67 %

6 m

6 m

Retrospective long-term analysis

(Lewandowski et al. 2009)

43

43

TACE

RE (glass)

PR 37 %

PR 61 %

18.7 m

35.7 m

Downstaging UNOS T3 to T2 31 vs 58 %; event-free survival 7.1 vs 17.7 m; no difference in TTP

(Kulik et al. 2006)

35

15 (RE glass)

19 (RE + Rx/RFA, LTx)

23 (T3 to T2: Rx, RFA)

8 (LTx)

66 m

Primarily only UNOS T3 patients (previous TACE only in 2)

(Inarrairaegui et al. 2012)

21

15 RE (resin)

6 (RE + LTx)

22 m

>41.5 m

Primarily only UNOS T3 patients (previous TACE only in 5)

So far, based on the yet limited but very promising data basis on effective downstaging after RE a recent international consensus conference for recommendations in liver transplantation in HCC stated that “newer strategies such as a combination of TACE with RFA and use of 90yttrium radioembolization or targeted therapies, have shown some benefits in preliminary studies” and therefore, “based on current absence of evidence, no recommendation can be made on bridging therapy in patients with UNOS T1 (≤2 cm) HCC”, but “in patients with UNOS T2 (one nodule 2–5 cm or three or fewer nodules each ≤3 cm) HCC (Milan criteria) and a likely waiting time of longer than 6 months, locoregional therapy may be appropriate;… no recommendation can be made for preferring one type of locoregional therapy to others” (Clavien et al. 2012). In consequence, a paradigm change on transplant concepts might happen in terms of keeping patients on a transplant waiting list and allowing for downstaging even if they are not eligible for listing any more due to progressive disease (Clavien et al. 2012). Further studies have to prove the potential benefit of such concepts.

Independently from the displayed options for downsizing and downgrading making a tumor resection, transplantation or local thermal or chemical ablation possible, there are situations where the remnant liver is too small in terms of functional reserve hindering any type of resection. However, there is already some evidence that lobar or segmental-selective RE may lead to ipsilateral/-segmental hepatic parenchymal hypotrophy and contra-lobar hypertrophy allowing subsequent surgery. In several case (Gulec et al. 2009; Seidensticker et al. 2012), reports and small studies including various types of tumors incl. HCC a volume increase between 21.2 % (Jakobs et al. 2008) and 35 % (Yoon et al. 2012) of the non-treated liver lobe after RE was described. Therefore, RE could become an important component in a multimodality treatment concept with curative intention—like preoperative portal-vein embolization, however, with an additional primary therapeutic impact on the targeted tumor (Anaya et al. 2008; Denys et al. 2012; Garden 2011).

3 RE as Alternative When Other Ablative Treatments Cannot Be Applied

Unfortunately, there are still a substantial number of patients who might be primarily not amenable for a local ablative treatment or will present significant progress after such a therapy. Therefore, high hopes were pined on sorafenib as systemic therapy in such cases which were fulfilled to some degree as the SHARP trial—a randomized controlled study comparing sorafenib to placebo—could show (Bruix et al. 2012). However, performing RE as a first-line therapy in patients similar to the patients included in the SHARP trial D’Avola et al. could gain an ample superior survival rate of 16 months in comparison to 8 months in a matched control group without RE (D’Avola et al. 2009). Despite the limitations of this study, the results with survival rates ranging from 9 to 16 months could be paralleled by several other studies and also by the study of the European Network on Radioembolization with Yttrium-90 Resin Microspheres (ENRY) as a subgroup analysis could show (Dancey et al. 2000; Hilgard et al. 2010; Lau et al. 1998; Sangro et al. 2011; Woodall et al. 2009).

Macro-vascular occlusion of the portal vein or its branches is considered as a dismal prognostic factor. It is in general an indicator for a progressed disease possibly associated with extensive intrahepatic tumor growth, extrahepatic spread and progressive functional impairment, and, therefore, often considered as a contraindication for TACE (Bruix and Sherman 2011). In consequence, many patients with portal-vein occlusion—often without differentiation between tumor thrombus and tumor ingrowth or central and peripheral branch thrombosis—are often excluded from a targeted therapy. Nevertheless, during recent years, the evidence is growing TACE with advanced technique can be performed successfully and may improve the patients survival (Luo et al. 2011). For example, in 125 patients with main portal-vein invasion, Chung et al. (2011) could demonstrate a significant superior survival in the TACE treated group (83 patients, 7.4 months median survival) in comparison to the supportive care group (42 patients, 2.6 months median survival) {Chung, 2011 #190, Vogl et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2011; Yoo et al. 2011; Yoshidome et al. 2011). Moreover, this results can be reproduced by RE as presented in recent studies achieving median survival rates up to 17 months (Carr et al. 2010; Denys et al. 2012; Inarrairaegui et al. 2010; Mazzaferro et al. 2012; Memon et al. 2012; Woodall et al. 2009; Yoon et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2009).

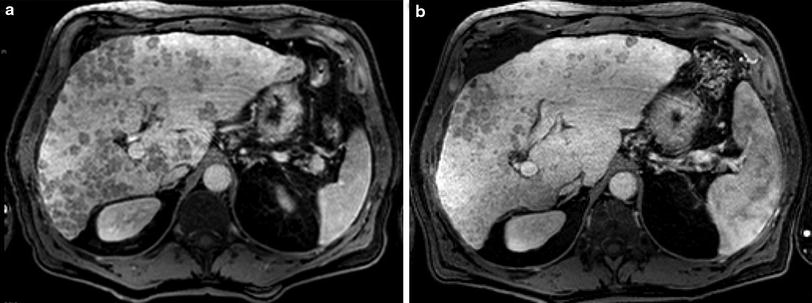

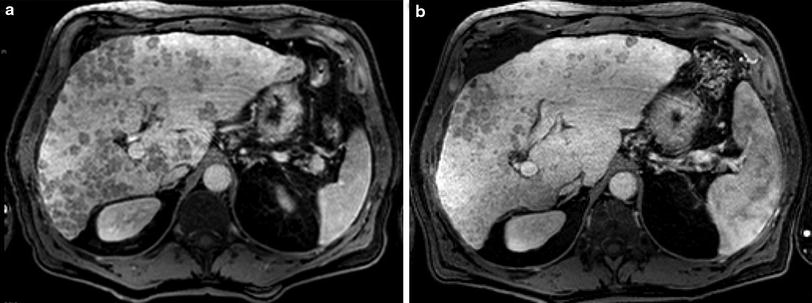

In consequence due to the excellent safety profile and an improved survival time in patients with poor prognosis RE and selective TACE might get the favorable therapy over systemic therapy in advanced and very advanced patients. Though to date, prospective studies comparing both treatment modalities in a randomized setting are lacking (Fig. 1. A 62-year-old patient with Child-Pugh A cirrhosis and multifocal HCC, intermediate Stage. (a) T1- MRI 20 min post Gd-EOB: bilobar, multinodular HCC. (b) 11 months post RE—2.2 GBq, synchronous bilobar application—significant reduction of tumor load, patent liver function, ECOG 0, no new tumor activity).

Fig. 1

A 62-year-old patient with Child-Pugh A cirrhosis and multifocal HCC, intermediate Stage. a T1- MRI 20 min post Gd-EOB: bilobar, multinodular HCC. b 11 months post RE—2.2 GBq, synchronous bilobar application—significant reduction of tumor load, patent liver function, ECOG 0, no new tumor activity

4 Radioembolization in Combination with Systemic Therapies

As discussed above, there is significantly growing study evidence establishing the place of RE within the therapeutic concepts for the different stages accepting RE as valuable component, e.g., in downsizing and downgrading of early HCC. Based on this results, the role of RE may expand to tumor stages where primarily no local therapy is employable due to anatomical (for local therapy unfavorable tumor location, e.g., within the dome or center of the liver, close vicinity to biliary or vascular structures) and/or functional restrictions (e.g., limited hepatic functional reserve). Moreover, most of the HCC patients will present in an intermediate or advanced stage where local ablation, resection or transplantation is not a therapeutic option in clinical reality. Unfortunately, in these patients no effective “classic oncological” therapy in terms of chemotherapy exists, actually all typical anti-cancer drugs failed in HCC.

Over the past 10–15 years, the insight into molecular carcinogenesis expanded dramatically. In many tumors a huge variety of molecular pathways responsible for malignant growth could be identified and used to develop targeted drugs (e.g., based on antibodies or specific cellular transporter inhibitors). In contrast to the many other gastrointestinal tumors, in HCC much more genetic alterations and variations in signaling pathways are involved creating a complex, multistep process of carcinogenesis resulting in the known molecular (and clinical) heterogeneity of HCC (Worns et al. 2009). Therefore, special attention turned on molecular targeted therapy in HCC since sorafenib among a variety of monoclonal antibodies (e.g., bevacizumab, cetuximab) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., sorafenib, sunitinib, erlotinib, gefitinib, lapatinib) could produce a moderate survival benefit over best supportive care in patients with advanced HCC as displayed in the SHARP trial (Llovet et al. 2008; Rimassa and Santoro 2009; Zhang et al. 2010).

Nevertheless, this result was and is encouraging numerous studies evaluating the potential advantageous effects of sorafenib on downsizing, improving time to progression, reducing relapse, prolonging survival, improving life quality, etc., at various stages in HCC. Worldwide at present, 167 studies (92 still open) on the use of sorafenib in HCC, 26 studies (15 still open) on RE in HCC and 6 studies comparing RE and sorafenib alone or both in combination are registered, and only 2 studies comparing RE and TACE (status at 1/2013; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) (Table 2).

Table 2

Recent phase I to III trials on RE and Sorafenib and RE and TACE (adopted from http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/)

Study | Phase | Status | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

NCT00846131: A Single-Center Proof of Concept Pilot Study to Evaluate the Safety, Efficacy, and Tolerability of Sorafenib Combined With Therasphere in Subjects With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Awaiting Liver Transplantation | I | Enrolling by invitation | Evaluation of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of Theraspheres® (also known as Y-90, or Y-90 Therasphere) combined with or without sorafenib (Nexavar®), in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, or liver cancer), awaiting liver transplantation |

NCT00712790: Phase I/II Study of SIR-Spheres Plus Sorafenib as First-Line Treatment in Patients With Non-Resectable Primary Hepatocellular Carcinoma (SIRSA) | I/II | Unknown | Evaluation of the safety and activity of chemoradiotherapy comprising a regimen of Sorafenib chemotherapy plus SIR-Spheres yttrium-90 microspheres, for first-line treatment of patients with HCC in whom surgical resection is not feasible |

NCT01126645: Evaluation of Sorafenib in Combination With Local Micro-therapy Guided by Gd-EOB-DTPA Enhanced MRI in Patients With Inoperable Hepatocellular Carcinoma (SORAMIC) | II | Recruiting | Evaluation of Sorafenib and local microtherapy guided by Primovist enhanced MRI in patients with inoperable liver cancer not suitable to TACE |

NCT01482442: SorAfenib Versus RADIOEMBOLIZATION in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma (Sarah)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|